For almost 80 years, Kirkus Reviews has served as the industry bible for bookstore buyers, librarians, and ordinary readers alike. Now Popdose joins the Kirkus Book Bloggers Network to explore the best — and sometimes the worst — in pop-culture and celebrity books.

This week, it’s a literary love story as sweet as nine kinds of pie…

The Hollywood blacklist was a formative trauma for a generation of American artists. From the late 1940s through the 1950s, powerful governmental organizations declared open season on the American left. J. Edgar Hoover was running the FBI as his personal fiefdom in pursuit of domestic enemies, real and imagined, with a special focus on rooting out supposed communist infiltrators in the entertainment industry. In 1947 the House Committee on Un-American Activities, which for years had been scrutinizing Hollywood product for signs of socialist propaganda, began a series of public hearings that would continue on and off through the end of the next decade.

The Hollywood blacklist was a formative trauma for a generation of American artists. From the late 1940s through the 1950s, powerful governmental organizations declared open season on the American left. J. Edgar Hoover was running the FBI as his personal fiefdom in pursuit of domestic enemies, real and imagined, with a special focus on rooting out supposed communist infiltrators in the entertainment industry. In 1947 the House Committee on Un-American Activities, which for years had been scrutinizing Hollywood product for signs of socialist propaganda, began a series of public hearings that would continue on and off through the end of the next decade.

Those hearings destroyed hundreds of careers. Only a few of those who testified served jail time for contempt of Congress, but many found themselves unemployed and unemployable — barred from work by informal agreements among the major studios and publishers. Not for advocating the overthrow of the government, mind you; but for the political indiscretion of caring about working people. The blacklists were a betrayal of their artistic calling; they were being called to task for the very idealism that art is meant to inspire.

Artists found different ways to get by during the blacklist years. Screenwriters like Dalton Trumbo might continue to find work, but had to go without credit or residuals. Lillian Hellman, her Hollywood career was nipped in the bud, she returned to writing for the stage. Beloved entertainers like Charlie Chaplin and Paul Robeson went into exile in Europe, while acclaimed film composer Elmer Bernstein was reduced, for a time, to scoring grade-Z cheapies like Robot Monster.

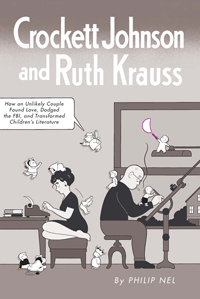

But there was one refuge for political freethinkers, where leftist talents could continue to enjoy popular and commercial success without concealing their identities: the world of children’s books. Langston Hughes, for instances, whose mainstream career suffered when his commentary on race relations drew the unwanted FBI attention, had a successful second act as a poet for children. Now, Philip Nel’s new husband-wife double biography Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss — released last week and charmingly subtitled ”How an Unlikely Couple Found Love, Dodged the FBI, and Transformed Children’s Literature” — offers a fascinating snapshot of this moment in the life (or afterlife) of American socialism.

Read the rest of this article at Kirkus Reviews!

Comments