For almost 80 years, Kirkus Reviews has served as the industry bible for bookstore buyers, librarians, and ordinary readers alike. Now Popdose joins the Kirkus Book Bloggers Network to explore the best — and sometimes the worst — in pop-culture and celebrity books.

This week, a new book chronicles one of the most acclaimed animators in television as he makes the leap to feature films, big budgets, and — eek! — Adam Sandler collaborations…

If we are living in a Golden Age of American animation — and although that’s an open question that only History can answer, signs point to yes — then the roots of this renaissance can arguably be traced to the mid-1990s, when Cartoon Network began to shift its focus from endless reruns of Scooby-Doo and towards original programming. The upstart cable channel soon established itself as a home for innovative young talents like Craig McCracken, Maxwell Atoms, and Danny Antonucci, all of whom brought idiosyncratic design sense and understated humor to a medium that had long been dominated by static, formulaic Saturday-morning fare. With quirky shows like Johnny Bravo, Ed Edd n Eddy, and The Powerpuff Girls, Cartoon Network threw down the gauntlet, spurring competitors like Nickelodeon and the Disney Channel to raise their games. The spoil of this artistic arms race fall to us, the fans; a bounty of whip-smart, great-looking cartoon shows.

If we are living in a Golden Age of American animation — and although that’s an open question that only History can answer, signs point to yes — then the roots of this renaissance can arguably be traced to the mid-1990s, when Cartoon Network began to shift its focus from endless reruns of Scooby-Doo and towards original programming. The upstart cable channel soon established itself as a home for innovative young talents like Craig McCracken, Maxwell Atoms, and Danny Antonucci, all of whom brought idiosyncratic design sense and understated humor to a medium that had long been dominated by static, formulaic Saturday-morning fare. With quirky shows like Johnny Bravo, Ed Edd n Eddy, and The Powerpuff Girls, Cartoon Network threw down the gauntlet, spurring competitors like Nickelodeon and the Disney Channel to raise their games. The spoil of this artistic arms race fall to us, the fans; a bounty of whip-smart, great-looking cartoon shows.

Genndy Tartakovsky was one of Cartoon Network’s young guns: creator of the indescribable Dexter’s Laboratory, vital creative voice in the early years of The Powerpuff Girls, and mastermind behind the hyperstylized, often wordless Samurai Jack. In recent years, Tartakovsky has been showrunner for the wildly popular Star Wars: The Clone Wars, sublimating his creative vision to that of George Lucas.

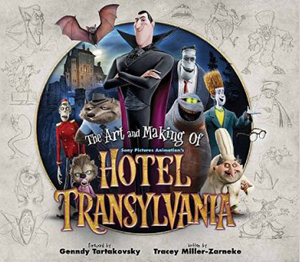

With Hotel Transylvania — which just wrapped its opening weekend — the Russian-born animator has made his first feature film. And Titan’s lavish new tome The Art and Making of Hotel Transylvania gives a gorgeous peek at how this whimsical monster mash came together.

Now, if you’ve listened to as many DVD commentaries as I have, a discussion of the making of a computer-animated film may evoke mind-numbing details of rendering speeds and processing power. But while author Tracey Miller-Zarneke doesn’t skimp on the tech talk, her text remains centered on the artistic process that led to the finished film.

Even moreso than traditional Hollywood product, feature animation employs a collective creative method. Work starts not with a screenplay, but with brainstorming sessions, where animators and designers pitch their takes on the various elements of the story, generating a pile of material that the director winnows through to shape the final narrative. Elaborate gags, subplots, even entire characters may be cut before the story attains its final shape. That’s why animated DVDs don’t tend to feature a lot of deleted scenes; most of the discarded bits and characters never progress beyond a few concept drawings, and are long-gone before a single frame of animation is rendered. The hundreds of sketches and paintings included here are the only evidence remaining of the different kinds of film that Hotel Transylvania might have been.

Read the rest of this article at Kirkus Reviews!

Comments