For more than 75 years, Kirkus Reviews has served as the industry bible for bookstore buyers, librarians, and ordinary readers alike. Now Popdose has joined the Kirkus Book Bloggers Network, taking to the virtual pages of Kirkus Reviews Online to dish on the best — and sometimes the worst — in pop-culture and celebrity books.

This week, we’re looking at a new collection celebrating the utter genius of the dumbest comic strip ever created…

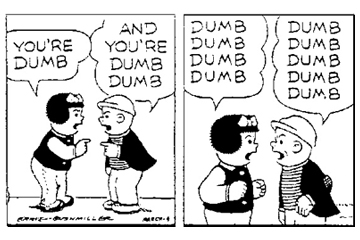

It’s hard to say just when and how the Cult of Nancy started. Oh, you’d always read the strip, but that’s just because it was always there, a lingering holdover from the mid-century, an era before the invention of such concepts as ”taste” and ”humor,” when the so-called ”funny pages” served the merely utilitarian function of filling the space in between the TV listings and the classifieds. Nancy — which dates in its current form to 1938, and which sees nigh on a thousand strips from its mid-40s run collected in a handsome new edition from Fantagraphics — seems, at first glance, the very model of a placeholder strip, a daily four-panel gag machine with no discernible drive or development. No one, upon opening their morning paper, ever turned immediately to the latest Nancy the way they did with Calvin and Hobbes, the way some people do now with Mutts. Frankly, Nancy was always kind of dumb.

It’s hard to say just when and how the Cult of Nancy started. Oh, you’d always read the strip, but that’s just because it was always there, a lingering holdover from the mid-century, an era before the invention of such concepts as ”taste” and ”humor,” when the so-called ”funny pages” served the merely utilitarian function of filling the space in between the TV listings and the classifieds. Nancy — which dates in its current form to 1938, and which sees nigh on a thousand strips from its mid-40s run collected in a handsome new edition from Fantagraphics — seems, at first glance, the very model of a placeholder strip, a daily four-panel gag machine with no discernible drive or development. No one, upon opening their morning paper, ever turned immediately to the latest Nancy the way they did with Calvin and Hobbes, the way some people do now with Mutts. Frankly, Nancy was always kind of dumb.

As it was meant to be. Writer/artist Ernie Bushmiller was creating with a broad and undiscriminating audience in mind — he referred to his readers, not dismissively, as ”gum chewers” — and if Nancy hit the lowest common denominator, then surely that was the point. But after Bushmiller’s death in 1982, interest in his work began bubbling up amongst comics creators and cognoscenti. Nancy became the subject of scholarly essays; select strips were released in small-run collections. Comics theorist Scott McCloud, an avowed fan, created the surreal card game Five Card Nancy, in which players use random photocopied panels from the strip to create non sequitur narratives that, as often as not, were no more nonsensical than the genuine article. As cartoonist Dan Clowes (Ghost World) notes in his astute introduction to this collection, oftentimes affectation begat affection; what began for many as ironic hipster ”appreciation” gave way, as readers delved into the mechanics an aesthetics of Bushmiller’s achievement, to a genuine recognition of his gifts.

Because Nancy possesses in spades the quality common to all great art: a singularity of vision. Bushmiller would often start drawing a strip with the final panel—the ”reveal” of the gag—and work backwards, so that every element of the completed strip would lead toward the joke, with no extraneous elements. The effect was literally unmistakable. The clarity and unity of purpose made it quite impossible to miss a single punchline…

Read the rest of this article at Kirkus Reviews!

Comments