For almost 80 years, Kirkus Reviews has served as the industry bible for bookstore buyers, librarians, and ordinary readers alike. Now Popdose joins the Kirkus Book Bloggers Network to explore the best — and sometimes the worst — in pop-culture and celebrity books.

This week, with San Diego Comic Con gearing up, we look back on one of comics culture’s finest hours…

The geeks have inherited the Earth — or at least the entertainment business. More than a 100,000 fans, celebrities, and industry players have descended on San Diego this week for the 42nd International Comic-Con; Marvel’s The Avengers is on its way to becoming the highest-grossing movie ever; and traditionally-cult genres like science fiction, fantasy, and the supernatural now rule the ratings and the bestseller lists. Cult is the new mainstream: Now, pop culture is nerd culture.

This ought to be a sweet moment — a demographic long ignored and ridiculed finds itself with an unprecedented cultural clout. The question is: What will they do with it?

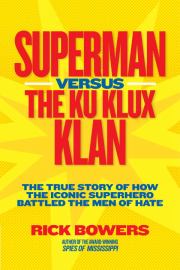

Sixty-five years ago, the burgeoning geek culture determined to harness its power for the public good. In Superman Versus the Ku Klux Klan — published late last year — journalist Rick Bowers tells the story of a 1946 campaign by the creators of the Adventures of Superman radio show to discredit the infamous white supremacist group, and help to nip its national resurgence in the bud.

It’s significant that Superman’s origins trace back to the earliest stirrings of what we would now identify as ”fan culture.” For a generation of fans, the postal service was a sort of slow-motion Internet — a way for like-minded individuals to connect, despite their geographical isolation. Co-creator Jerry Siegel was an early science-fiction fan, and his first writings were in mimeographed zines distributed to a network of correspondents he’d cultivated via notices printed in the back pages of the pulps.

Bowers splits his narrative track between the trajectory of Superman’s first decade — from his origin in Siegel’s attic studio to his mass-media ubiquity — and a potted history of the Ku Klux Klan in its various incarnations. Founded in 1866 as an apolitical fraternal organization (with, although Bowers doesn’t draw the connection, a fannish bent of its own: the dress-up pageantry and the elaborate mythology made the first Klansmen something of proto-cosplayers), the Klan was soon reinvented an anti-Reconstruction terrorist group.

Flaming out in the 1880s, the Klan was revived for the 20th Century as a national organization, pushing a new anti-Semitic, anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic agenda — while spinning cash for its top leaders, in the form of membership dues and merchandising. And all of it was tax-free, since the new Klan was incorporated, rather improbably, as a charitable organization. Before a string of scandals brought the organization down, the Klan had made huge inroads nationwide, even in such unlikely places as New Jersey, Connecticut, and especially Indiana, where membership topped out at nearly half a million.

The KKK made another bid for national prominence in the 1940s, and that’s where Bowers brings in the third strand of his narrative — the exploits of a crusading journalist named Stetson Kennedy, a native Southerner who made it his mission to take the Klan down. Kennedy, who died last year at the age of 94, was a problematic figure. While he undoubtedly did much to expose and discredit the white supremacist movement — in the 1940s he infiltrated several Klan-affiliated groups under an assumed identity, risking his life many times — he was also a shameless self-promoter, often taking credit for the work of others and exaggerating his own role in events.

This causes some trouble in integrating his story into the other narrative threads. While everyone agrees that the producers of the Superman radio show consulted with Kennedy before creating their 16-part serial ”Clan of the Fiery Cross,” reports vary as to how much he actually contributed to the program. In Kennedy’s own account, it was he who pitched the idea to them, even contributing a draft of the script; but everybody else seems to agree that the notion actually came from Superman’s corporate sponsor, Kellogg’s…

Read the rest of this article at Kirkus Reviews!

Comments