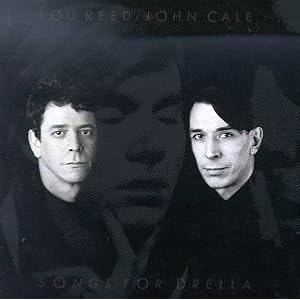

The death of a loved one or mentor can do interesting things, one of which is to mend relationships which could not be fixed during the course of the deceased’s remaining years. Such was the case of Lou Reed and John Cale, original members of the Velvet Underground. Practically estranged since Cale’s departure/removal from the band in 1968 (with the exception of a single collaboration in 1972), it took the death of their original manager and producer, pop art legend Andy Warhol, to bring them back together. While the shaky truce would be pushed to its limits as they worked together on a cycle of songs in honor of Warhol, the resulting album, Songs for Drella, would not only prove to be a grand work, but helped plant the seeds for a reunion (albeit brief) of the classic Velvet Underground lineup.

In the Summer of 1988, a year after Warhol’s death, Cale played Reed songs he was working on as a “biographical” tribute to Warhol. Reed asked if he could join in on the project, and together they finished the work. While much truth about Warhol and the effect he had on others is contained in the work, it is described as a “fiction” in the liner notes. Some songs, like Cale’s dark, spoken “A Dream”, attempt to put Warhol’s private thoughts into words, almost creating yet a new image of Warhol in describing their own images of him . A truncated version of Songs for Drella — Drella was one of Warhol’s nicknames; a combination of Dracula and Cinderella — was played live in January 1989, and a finished version, containing the 15 songs that would appear on the recorded version, premiered in November 1989 at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. A short time later, Cale and Reed met in the studio to record the album version of Songs for Drella, which, with its very few overdubs and live vocals, is almost a direct recreation of the minimalist live shows.

As members of Andy Warhol’s Factory during its heyday, both Cale and Reed had not only close proximity to the artist, but seemingly gained direct experience as to who Warhol was as a human being, and what his actual philosophies on art were. Thus you have Reed talking about Warhol’s background in “Small Town”, and his desire to leave, get to New York, and try to ingratiate himself with his idol, Truman Capote. The next two songs, Reed’s “Open House” and Cale’s “Style It Takes” look at the beginnings of the Factory from two different perspectives. Reed focuses on getting the public in for free to view his art, providing gifts and food in accordance with the tools he learned from his Czech immigrant parents. Cale then looks at the goal of gaining patronage once you get people through the door, and keeping them interested by trading their public connections for his promises of fame. In many the next songs, “Work”, “Trouble With Classicists”, and “Images”, both Reed and Cale lay out Warhol’s concept of art as product; the interchangability of form and function; how the most important thing about creation is to create, even if what is created is done in repetition; and that there is a beauty — a super-reality — in the unadorned and ugly.

Most of the second half of the song cycle is a lot more emotional and internalized compared to the first half. “Slip Away (A Warning)” and “It Wasn’t Me” speak of the destruction and early deaths that came to many “Superstars” associated with the Factory (Fred Herko, Andrea Feldman, Edie Sedgwick, Candy Darling, etc.). While not everyone is specifically namechecked, Reed-speaking in the voice of Warhol-defiantly refuses to take the blame for what happened to the Warhol Superstars; that he provided the means of success: “I showed you possibilities” but that “The problems you had were there before you met me”. Even more direct language comes out in Reed’s “I Believe”, about Valerie Solanis, a Factory hanger-on who shot Warhol in 1968 in a state of delusion that the artist was controlling her. It doesn’t get more blunt than lines like “And I believe there’s got to be some retribution / I believe an eye for an eye is elemental / And I believe that something’s wrong if she’s alive right now.” Perhaps ironically, Solanis had likely just died (on April 25, 1988) when Reed was composing this.

The album ends with two statements of summation regarding Warhol. First comes “Forever Changed” from the point of view of the artist himself, likely late in his life, reflecting on how he had literally transformed himself twice, first by moving to New York and becoming part of the art world, and then by becoming an living icon known as much for his image as for his actual work: “Got to get to the city – get a job / Got to get some work to see me through / My old life’s disappearing from view.” Finally, Reed sings an open-letter elegy to Warhol in “Hello It’s Me”, apologizing for not understanding him as well as he thought he did, for not appreciating him enough when he was alive, and hoping that he might find Songs for Drella an appropriate tribute: “Oh well now Andy – guess we’ve got to go / I hope some way somehow you like this little show / I know it’s late in coming but it’s the only way I know.” It’s a beautiful ending to what turns out to be a highly dramatic and emotional work, even though it is delivered at times in the very stolid, post-modern art rock format that made the Velvet Underground legendary in the first place. The honesty and affection that exist with the songs elevate and give additional meaning to the minimalist, sometimes droning soundscapes, letting the listener experience a truly stunning portrait of the late artist, even if Cale and Reed attempt to hide behind the facade of fictional representation. In a way, it’s a play on form versus function within art, much like what Warhol himself often did.

A final note: While at the completion of the studio recording process John Cale stated that he would never work with Lou Reed again, a funny thing happened a few months later: On June 15th, Cale and Reed reconvened again to play selections of Songs for Drella at the Fondation Cartier concert in Jouy-en-Josas, France. At the end of the set, Cale and Reed emerged for an encore….with Maureen Tucker and Sterling Morrison, and the classic lineup of the Velvet Underground played “Heroin” together for the first time in 22 years. This moment would eventually lead to a full blown reunion of the four as the Velvet Underground through parts of 1992 and 1993 before they broke up yet again, this time during negotiations for an episode of MTV Unplugged. (Any further reunion possibilities were quashed forever two years later when Sterling Morrison died of cancer.) Considering all this, it seems even more amazing that not only were Cale and Reed able to set aside a good part of their differences for a year to create new music, but that the end result was such a well crafted song cycle.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=be352f0a-5b74-415c-bbe6-ff18b1955e30)

Comments