For much of the 1980s, New York’s Sonic Youth made an artful racket that was way too hip for most of us. It took until the late 90s for me to find anyone who had a deep passion for the band (or rather, for a couple of SY fanatics to find me and lock me in a padded cell with a homemade cassette sampler of the band’s coolest shit), and by that point I was ready to be converted. But in 1990, this was a band none of my friends nor I were into, that I read about from afar, thinking their name was kind of lame and consequently refusing to buy into the hype.

For much of the 1980s, New York’s Sonic Youth made an artful racket that was way too hip for most of us. It took until the late 90s for me to find anyone who had a deep passion for the band (or rather, for a couple of SY fanatics to find me and lock me in a padded cell with a homemade cassette sampler of the band’s coolest shit), and by that point I was ready to be converted. But in 1990, this was a band none of my friends nor I were into, that I read about from afar, thinking their name was kind of lame and consequently refusing to buy into the hype.

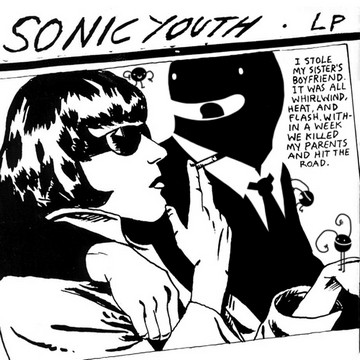

And there was plenty of hype. Thurston Moore, Kim Gordon, Lee Ranaldo and Steve Shelley had been recognized for a few years already by the usual mainstream rags (Rolling Stone, Spin and the like) for indie masterpieces like 1987’s Sister and 1988’s Daydream Nation. The former first appeared on SST, the label that brought us HÁ¼sker DÁ¼ and the Minutemen. The latter album could technically be considered a major label record even in its first issue — on the Capitol-distributed Enigma label, which, while having built a stable of historic punk releases during its tenure, is primarily remembered as the imprint responsible for foisting Poison unto the world. Minor qualifications aside, Goo is generally considered the band’s major label debut.

Any fears that the famously idiosyncratic band would soften up or otherwise ”sell out” were quickly put to rest from the very first tune. Thurston Moore’s ”Dirty Boots” is as riotous and memorable a song as any of the band’s previous classics. The sound was a little cleaner than their earlier records, but still raw enough that Thurston’s and Lee’s customized dual 6-string attack-via-avant-garde-orchestration lost none of its power. If anything, Goo confirmed that Sonic Youth were forever disciples of out-there American avant garde composer Glenn Branca, even as they continued to indulge in the ethos of punk rock, as well as pop culture references that seemed ironic on the surface, but were in all actuality quite sincere (see 1989’s cover of Madonna’s ”Into the Groove,” released under the band name Ciccone Youth — not to mention the close-up of Madonna’s face on the album cover, which was personally approved by Madonna herself).

Any fears that the famously idiosyncratic band would soften up or otherwise ”sell out” were quickly put to rest from the very first tune. Thurston Moore’s ”Dirty Boots” is as riotous and memorable a song as any of the band’s previous classics. The sound was a little cleaner than their earlier records, but still raw enough that Thurston’s and Lee’s customized dual 6-string attack-via-avant-garde-orchestration lost none of its power. If anything, Goo confirmed that Sonic Youth were forever disciples of out-there American avant garde composer Glenn Branca, even as they continued to indulge in the ethos of punk rock, as well as pop culture references that seemed ironic on the surface, but were in all actuality quite sincere (see 1989’s cover of Madonna’s ”Into the Groove,” released under the band name Ciccone Youth — not to mention the close-up of Madonna’s face on the album cover, which was personally approved by Madonna herself).

Goo’s biggest nod to an infinitely more well-known figure came in the form of Kim Gordon’s ”Tunic (Song For Karen)” — as in Karen Carpenter. Kim recites the first-person lyrics as poetry over the band’s thumping background, her voice echoing as if she really was Karen Carpenter off in the deathly distance — reflecting on her anorexia, calling out to her brother Richard, jamming up in heaven, and hanging with Janis Joplin, Elvis Presley and (presumably) Dennis Wilson. (SY would raise a toast to the Carpenters again four years later with an eerie cover of ”Superstar” on the If I Were a Carpenter tribute album.)

Public Enemy’s Chuck D further added to Goo’s star power (pun intended, sue me) with a ”yeah” and a ”word up!” on the album’s best-known song, ”Kool Thing,” in which Kim Gordon mocked her own feminism (“are you gonna liberate us girls from male, white corporate oppression?”) via Chuck D (”fear of a female planet / fear, baby!”) as she made repeated knocks (another shameless pun, woo hoo!) at one L.L. Cool J (“I don’t think so”).

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/SDTSUwIZdMk" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

Overall, though, the famous people (present or dead) weren’t what carried Goo. Entering a new decade in which relations between the sexes would fall off balance in ways far different from previous decades even as progress continued to be made, Goo demonstrated a band that was remarkably balanced — Kim and Thurston, as the so-creative-and-awesome-they’re-almost-sickening couple that fronted the band, were pretty much split down the middle with their contributions. Kim was the John Lennon to Thurston’s Paul McCartney, while Lee functioned as the band’s George Harrison with his single obligatory contribution — the one that always feels the most human, like it’s coming from a regular guy rather than a superstar. Steve, of course, never sings — he knows his place is behind the drum kit. Throw in a couple of short near-instrumental blasts as palate-cleansing bridges (”Mildred Pierce” and ”Scooter + Jinx”), and you have one of the most perfect Sonic Youth records ever made. I’d even go so far as to call it their last perfect record until they practically became reborn as the ultimate indie punk jam band in 2002 with Murray Street.

And with that, Sonic Youth not only began an 18-year run as one of the most awesome indie bands to jump to a major label and never lose sight of themselves, but also used their newfound position to help precipitate the signing to their new label of a certain Seattle band led by a dirty blond punk who once claimed to live under a bridge, the one we all called Kurt.

Comments