Gordon Sumner was blocked. Ever since the death of his father he found he could write music, but was unable to come up with any lyrics. The death of his mother a few years previous had had seemingly the opposite effect, resulting in the double album …Nothing Like the Sun. But that album was able to come easily because he didn’t feel the need to express his grief and feelings for his mother throughout the album’s lyrics. Instead, he merely plunged into his music, let his interests lead him wherever they may, and then expressed his appreciation for his mother by dedicating the finished work to her. Besides the album note, the most his mother “came through” on his 1987 album was in the sad tone of select songs, such as the singles “Fragile” and “Be Still My Beating Heart”. With this new set of half-written songs, though, something was different: the need to put his grief-his relationship with his father-directly into the music was somehow necessary in this project. And so these half finished pieces sat, some of them for as long as two years, before finally, in the early part of 1990, Sumner found himself able to match up some words with one of his more somber tunes:

Gordon Sumner was blocked. Ever since the death of his father he found he could write music, but was unable to come up with any lyrics. The death of his mother a few years previous had had seemingly the opposite effect, resulting in the double album …Nothing Like the Sun. But that album was able to come easily because he didn’t feel the need to express his grief and feelings for his mother throughout the album’s lyrics. Instead, he merely plunged into his music, let his interests lead him wherever they may, and then expressed his appreciation for his mother by dedicating the finished work to her. Besides the album note, the most his mother “came through” on his 1987 album was in the sad tone of select songs, such as the singles “Fragile” and “Be Still My Beating Heart”. With this new set of half-written songs, though, something was different: the need to put his grief-his relationship with his father-directly into the music was somehow necessary in this project. And so these half finished pieces sat, some of them for as long as two years, before finally, in the early part of 1990, Sumner found himself able to match up some words with one of his more somber tunes:

Under the dog star sail

Over the reefs of moonshine

Under the skies of fall

North, north west, the Stones of Faroe

The sailing imagery immediately brought up feelings about his father, who had wanted to be a sailor for the better part of his life (like most of his family had been), but instead had settled into jobs such as being a fitter at an engineering firm and a milkman with his own small dairy, in order to support his wife and four children. Suddenly, the bond between the poetic and the personal was formed, and Sumner found himself able to finally address his feelings, not just in the symbolic context of the sea, but as seen in the key lyrics from this song, the personal hold that his father’s passing had on him:

Sometimes I see your face,

The stars seem to lose their place.

Why must I think of you?

Why must I? Why should I?

Why should I cry for you?

Why would you want me to?

And what would it mean to say,

That, “I loved you in my fashion”?

The stars from the beginning of the song-the stars meant to guide the sailor home-become jumbled in visions of the deceased and cause him to lose his way, much like Sumner’s inability to seemingly grieve for his father and move on have caused him to lose his way as an artist. To put a fine point on it, he wants to know why such a state even exists; and furthermore, what would his father say if he was to hear that his son had fallen into such a state? What would it mean to him to hear his son loved him, and couldn’t deal with his absence to such a point that it prevented him from doing what was considered his job? Is that fair to the son? Is it important to the father? Partly traditional folk song, partly Camus-styled existentialism, the lyrics to “Why Should I Cry For You“, the centerpiece of The Soul Cages, is a shockingly honest contemplation on not just death, but the personal toll that can often take place in the mourning process, and often go under-addressed out of respect for the dead.

Once this first hurdle had finally been cleared, the man better known as Sting was able to come up with lyrics for seven other songs (one tune, “Saint Agnes and the Burning Train” would remain an instrumental on the album), almost all of them dealing with the same imagery of death and the sea, from the opening tale of “Island of Souls” where the father of protagonist Billy (who would appear in both name and allusion in other songs on the album), a ship riveter, is mortally wounded in an industrial accident, through to the album’s title track, which in its last minute reincorporates the last verse (musically and lyrically) of the album’s opening song–Billy’s dream of his father’s final resting place:

He dreamed of the ship on the sea

It would carry his father and he

To a place they could never be found

To a place far away from this town

A Newcastle ship without coals

They would sail to the island of souls

Throughout the album, the songs are arranged to give a cohesive feel that matches the lyrics in subject and sound. Unlike his first two solo albums, Sting’s The Soul Cages is relatively stripped down, featuring a new band “anchored” by former E-Streeter David Sancious, who provides various keyboard sounds, from classic B3 organs, to mood setting synth washes, to programmed horn pipes. Jazz great and often Sting sideman Branford Marsalis provides alto sax fills on a number of tracks to add appropriate tone to the proceedings, and Producer/Engineer Hugh Padgham makes the wise choice of miking Manu KatchÁ©’s drums to give them both a crispness and echo effect throughout most of the album that sounds very much like the pulsing beats used throughout history to keep oarsmen in time. The final product is arguably Sting’s high point as a solo artist, and actually spawned his final Top 10 hit in the United States with “All This Time“, one of the few upbeat songs on the album, at least musically. Between the joyous arrangement and a video that played upon the stateroom scene of the Marx Brother’s A Night at the Opera, many people might have not totally focused on the lyrics about death and criticism the Catholic Church.

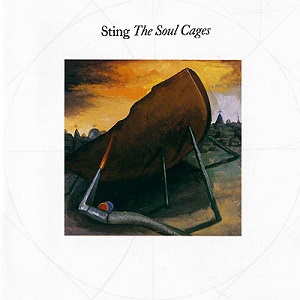

A final irony should be pointed out as to The Soul Cages: As both an artist and a person in general, Sting has been very conscious about showing himself off: from his infamous “metal underwear” scene in the film Dune, to the documentary footage he had made of himself doing yoga, to various…uummm….artistic photos he’s had taken, Sting is the type of guy who seems to really get off on letting people know “I am Sting! A fine physical specimen indeed, no?” But for The Soul Cages, perhaps his most personal work, what does the album cover lack?: Sting. Instead, there’s a painting of a boat moored on the beach, and a number of church steeples in the background. It is the only solo album Sting has released of original work that does not show him on the cover, perhaps because in The Soul Cages, the rock legend Sting wasn’t really there: he simply became Gordon Sumner again, a boy grieving over his father’s death.

Comments