February 9, 1964. 8:00pm. The click-clack of changing dials rings through American homes as the fuzzy gray picture on the television screen clears to reveal the gleaming eye of CBS and The Ed Sullivan Show. Sullivan is a religion for America’s families (not least of which is the fictional McAfees, who put their dreams of an appearance to song in Bye, Bye Birdie). Tonight, however, is special. Momentous, even. Life-changing for the eager youth poised nose-to-nose with the set.

Because within that golden hour, those precious 60 minutes, American households discovered the Beatles; the Sixties, and the future of music as we know and appreciate it today, were born.

Though radio stations and record shops were crushed with demands for the Beatles’ music prior to the airing, for many young folks, this was the first time they had seen the Fab Four in motion as living, breathing young men. They could almost touch them.

That fateful evening is so ingrained in many memories, almost to the point of fable, that sometimes it’s taken for granted. Of course the Beatles played on Ed Sullivan, of course they came to America, and of course they were a smashing success. But how did they get here, and, more importantly, who brought them?

All answers unequivocally point to one man: the Beatles’ manager, Brian Epstein.

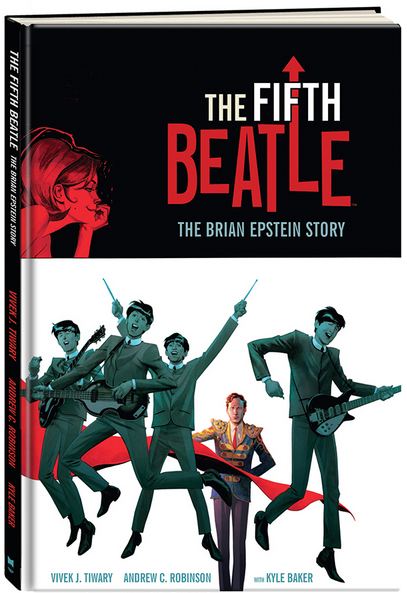

”I will go on record and say that, without Brian, the Beatles would have never come to America,” says Vivek Tiwary, author of The Fifth Beatle, a new graphic novel chronicling Epstein’s years with the Fab Four.

Epstein had had America in his sights practically as long as he’d represented the Beatles. After plucking them from the damp basement scene of the Cavern in 1961, Epstein fitted them with sharp, tailored suits, taught them the art of performance, and carefully sculpted the band’s public persona, while allowing them to remain honest, genuine young men from largely working-class backgrounds. He was a showman, a theatreman, and an intuitive businessman who recognized talent immediately.

Rapidly outgrowing their native Liverpool, the Beatles toured the UK extensively two or three times a year in the early 60s. As their popularity grew, so did the hit records — and the hysteria.

”I find all large gatherings of fans immensely exhilarating and thrilling,” said Epstein, ”I hope Beatle crowds continue to scream themselves hoarse in a frenzy of exultation.”

It was quite clear that Epstein was dealing with an as-yet-unseen phenomenon, and that he had been right all along that the band offered something radically new and refreshingly different that the world desperately needed. With all the fanfare of the great Spanish bullfighters that he adored, Epstein and ”his boys” captured home territory, and he knew that it was time to look west, across the Atlantic.

In early 1963, he struck a deal with New York concert promoter Sid Bernstein to book the band at Carnegie Hall, vowing to call it off if the Beatles didn’t have a U.S. hit by the end of the year. The two agreed on February 12, 1964 (Lincoln’s birthday — Bernstein chose a date when kids wouldn’t have school), and closed the deal with a ”telephone handshake.”

Epstein then knew that the time to strike America was imminent, and, when he received news in January 1964 that the Beatles’ ”I Want To Hold Your Hand” shot to #1 in the U.S., he knew it was time to solidify plans he’d laid the previous year with America’s most notorious entertainment impresario: Ed Sullivan.

Sullivan experienced a rather jarring introduction to Beatlemania. He and his wife happened to be flying out of London Airport in 1963 when mobs of screaming girls warranted a shocked Sullivan to ask what all the hubbub was about. When he learned the commotion was over a group called the Beatles, returning from Sweden, Sullivan remarked, ”Who the hell are the Beatles?”

Epstein, meanwhile, received a phone call from one of Sullivan’s agents who had seen the band perform in London. He wanted to meet while Epstein was, coincidentally, in New York the following week, but Epstein preferred to do direct business with Sullivan himself. A meeting was arranged and, on November 11, 1963, Brian Epstein and Ed Sullivan sat down to negotiate inside Sullivan’s suite at the Delmonico Hotel.

Sullivan offered a slot on one show.

Epstein insisted on headlining three shows, with the first on February 9, three days before the booking at Carnegie Hall.

Sullivan shirked at the cost.

Epstein halved the appearance fee, agreeing to $10,000 for all three appearances. (Col. Tom Parker had negotiated $50,000 for Elvis.) He, personally, would make up the difference.

They had a deal.

(In The Fifth Beatle, Tiwary depicts Epstein negotiating with Sullivan. Well, except that Sullivan is speaking through a ventriloquist’s dummy, an occurrence that Tiwary neither confirms, nor denies.)

Although Epstein called Sullivan a ”genial fellow” in his autobiography, A Cellarful of Noise, Sullivan was reportedly frustrated with Epstein’s need to control every aspect of the production, down to the exact wording of the Beatles’ introduction. Presentation was of utmost importance to Epstein, and he wasn’t going to take any chances.

Ed Sullivan would later tell The New York Times that he recognized Beatlemania as the same type of hysteria inspired by Elvis, but he initially didn’t share Epstein’s view that the Beatles would become the ”biggest thing in the world.” Sullivan thought it was ”ridiculous” to give them top billing because a group, least of all an English group, hadn’t had success in the U.S. in a long time. It took four days to settle the shows’ performance order, and, in the end, Epstein got exactly what he wanted.

And the rest, as they say in movies, is history.

Today, celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Beatles’ performance on Sullivan, it is fitting and, in fact, rather obvious that Epstein receive accolades as well: after decades of lobbying by supporters, artists, and fans, Brian Epstein will finally join the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame with the Class of 2014.

”It’s great to see Brian finally getting his due,” says Tiwary, who calls Epstein his ”historical mentor.” While a student at Wharton, Tiwary stumbled upon Epstein and felt an immediate connection to him. ”I know what it’s like to feel like an outsider, being an Indian-American in the entertainment industry. Brian felt that way his whole life; he was gay at a time when homosexuality was a crime. He was Jewish during a period of rampant anti-semitism.”

Finding that virtually nothing had been published about the industry legend’s life and work, Tiwary decided to take on the task himself, interviewing Epstein’s family, friends and colleagues multiple times over a 20-year period. His efforts culminated in The Fifth Beatle, a gorgeously-illustrated telling of Epstein’s prime years. Part fact, part fantasy, the book paints Epstein as the justifiable hero of the Beatles story in an easily readable — and entertaining — format. There are currently plans in the works for a film as well.

Though Tiwary agrees that Epstein was indeed a hero, he calls him ”an imperfect one.” A chief criticism of Epstein as manager was his oversight in underestimating the value of the Beatles’ merchandising rights. ”Before the Beatles, no one was selling merchandise. T-shirts were for promotion, and no one had the idea to make money off of them,” Tiwary says. ”Brian made mistakes, but he was also the first one to break ground in the music industry the way that he did — there was no precedent before him.”

Though Tiwary agrees that Epstein was indeed a hero, he calls him ”an imperfect one.” A chief criticism of Epstein as manager was his oversight in underestimating the value of the Beatles’ merchandising rights. ”Before the Beatles, no one was selling merchandise. T-shirts were for promotion, and no one had the idea to make money off of them,” Tiwary says. ”Brian made mistakes, but he was also the first one to break ground in the music industry the way that he did — there was no precedent before him.”

Epstein, who died at age 32 in 1967, managed other significant rock acts like Billy J. Kramer and the Dakotas, Cilla Black, and Gerry and the Pacemakers throughout his short-lived career, but no one could ever compare to John, Paul, George and Ringo. Even though his day-to-day management lessened when the band stopped touring in 1966, his untimely death left them without a figurehead and, it could be argued, led to the group’s ultimate undoing. “When Brian died, I thought, ‘We’ve fuckin’ had it,'” said John Lennon.

For his faults, it was Epstein’s single-minded vision of success for ”his boys” that propelled the Beatles into everlasting fame. Without someone who could dream as big as him, or speak as boldly, Americans probably wouldn’t remember where they were on February 9, 1964, or who Ed Sullivan’s guests were. Epstein’s resolve was not only travel to America, but conquer it.

As he himself told The New Yorker at the end of 1963, ”I think that America is ready for the Beatles. When they come, they will hit this country for six.”

Comments