Since the announcement of Neil Peart’s death on January 10, 2020, there’s been an outpouring of tributes, obituaries, and other remembrances of a man who valued his privacy over the trappings of celebrity. Being the drummer and primary lyricist for Rush — a band often called the biggest cult band in the world — came with baggage that Peart probably wished was never there. The zealotry of fans, for one. Being fanatical about a band was not something Peart thought was bizarre or strange. As a teenager, he loved The Who, so he understood the power music and lyrics have on a young person’s ears. Despite his single-minded dedication to rock drumming — often channeling the spirit The Who’s Keith Moon — and his deep admiration for Pete Townshend’s lyrics, he said he could never imagine a scenario where he’d stalk them as a teenager. Even when he had an opportunity to meet Pete Townshend in 2012, Peart kept his cool by mostly talking about how much he enjoyed Townshend’s 1985 short story collection, Horse’s Neck.

To be a slobbering fanboy in front of one of his rock idols was not in Peart’s hard wiring. So, he found it odd and unsettling that his fans often had no sense of boundaries when it came to his privacy — which is probably why he traveled with a security detail during Rush tours. As he wrote in one of his seven books, Roadshow, it gnawed at him that people thought he was a dick because he valued his privacy outside the Rush Machine. How could people who didn’t know him at all think so badly of him? Instead, he summed up his relationship with his fans with a quote ascribed to Humphrey Bogart: ”The only thing I owe the public is a good performance” — which, if you ever saw Rush live, you would know he lived up to that promise every night. Later in his career, he’d remind people that he’s actually a very shy person. Talking about himself or the importance of his work with fans made him feel awkward, uncomfortable and looking for the exits. He added that if you met him in a small town diner somewhere in North America — and had no idea who he was — he’d be incredibly social and talkative. However, the moment when someone does recognize him is the very moment he starts to shut down and put up defenses to protect himself from guys (and it was mostly guys) who would tell him how much this or that song meant to them or wanting to be pals for life. When Peart wrote the lyrics for Limelight” — and most notably the line ”I can’t pretend a stranger is a long awaited friend” — it was before the band’s fame and fortune really took off. If he was feeling leery about fanboys in 1980-81, that feeling of dread was certainly far worse after the Moving Pictures Tour made Rush rock stars.

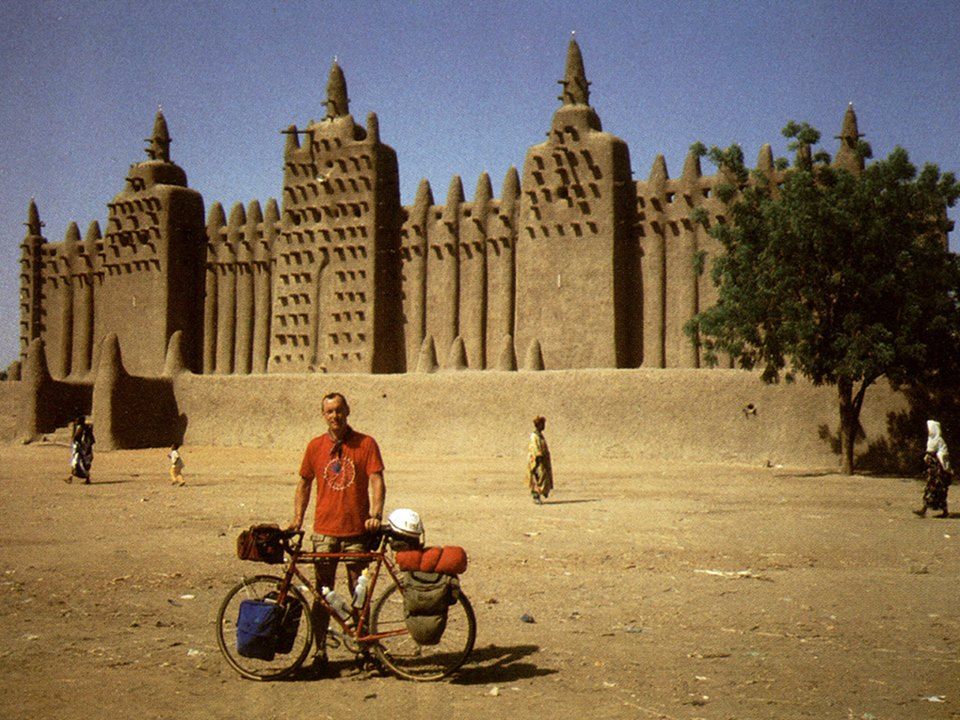

Peart captioned this selfie “Are you serious?” It could easily be the way he reacted to the adulation of fans.

I note the great lengths Peart went to protect his privacy to illustrate another reason why: the guy loved experiencing the beauty and awe of the world — without feeling like he was the center of it. From the grand, to what some would consider the mundane, Peart’s adventure travels were chronicled in his books. Whether it was cycling through three West African countries with a group, riding over 55,000 miles on his motorcycle after the deaths of his oldest daughter and first wife in the 1990s, his love of snowshoeing, bird watching, cross-country skiing, stamp collecting, hiking, swimming, and reading, it was clear that he found incredible joy and a sense of healing while being an active participant in the world. After he remarried and eventually had a child with his second wife, domestic bliss rarely meant retreating from little and big adventures. In more than one interview, Peart often said that he lived by the motto: ”What’s the most excellent thing I can do today?” That, to me, is a guy for whom experiences were an integral part of living a life where — to quote a lyric from ”Headlong Flight” — he wouldn’t trade tomorrow for today.

Much has been made of Peart’s professed atheism — especially after his older daughter Selena and first wife Jackie died in 1997 in and 1998. I used to belong to a couple of Rush online groups during that period, and a good number of fans noted that while they knew Peart was an atheist, they hoped the deaths of his family members would get him to believe in God. Well, that didn’t happen. In ”Faithless” he was quite upfront that his own ”moral compass…beats a spirit in the sky.” Rather than engaging in polemics, though, he asserted that clinging to hope and believing in love is enough for him. I’ve often wondered what hope meant for Peart. It’s a word that conjures a sense that something will turn out favorable in the end. But there are other interpretations that run deeper than that. I don’t know if Peart ever read anything by Cornel West, but West often says he’s ”prisoner of hope.” It’s not hope borne out of optimism, though. Rather, West says that hope is the refusal to succumb to despair and nihilism. Considering the kind of tragedies befall us all in life, sinking into despair and even nihilism are clearly things one wants to avoid if you’re living an engaged existence that celebrates the sheer force of life. Losing family members and friends is something all of us experience. Some of us find solace in religion. Others, even with words and deeds meant to comfort, may fall into despair. Peart certainly felt those things in 1997-98 — and found that only through the motion of travel on a motorcycle could his wounded ”baby soul” find comfort among the wonders of the world. And so it was with love. Peart met Carrie Nuttall in 2000 after the band’s photographer (Andrew MacNaughtan) played matchmaker for his widowed friend. The couple married a year later and Nuttall gave birth to their daughter Olivia in 2009. After realizing that he spent little time with his first daughter — partially because of Rush’s relentless touring and recording schedule — Peart vowed not to repeat what he did in the past. Though he was pulled back to work for three more tours and one album (Time Machine in 2010, Clockwork Angels in 2012, and R40 in 2015), he was reluctant to leave his daughter for extended periods of time. So, while Rush calling it quits in 2015 was very sad for fans who had become used to the band being active since their ”comeback” record Vapor Trails in 2002, Peart must have felt relief that he was finally free of the itinerant life of a touring musician.

Alas, those post-music years came with a cancer diagnosis — which Peart kept private right up to his death on January 7, 2020. Most reports say he was battling cancer for 3 ½ years, but The Guardian suggested a longer time frame of five years. Whatever the case, Peart’s retirement probably did not mean he retired from life. Certainly, the aggressive form of cancer he had amplified the limitations of time. It’s that limited time Peart probably took advantage of with his wife, daughter, parents, sisters, brother, and friends — while an invisible countdown clock ticked down.

How he spent those last years of his life is entirely a private matter.

Publicly, Peart leaves a number of books that detail his experiences both with Rush and on his own — ironically, often told in a personally revealing manner. However, it’s the music he created with Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson under the band name Rush that will stand as an example of how talent, hard work, chemistry, and artistry led to a unique form of musical excellence in rock music. Those moments are preserved in recordings that can still motivate, inspire, or be a catalyst for just rockin’ out.

The treasure of a life is a measure of love and respect

The way you live, the gifts that you give

In the fullness of time

It’s the only return that you expect — “The Garden” lyrics by Neil Peart

Comments