So this week the geek world (Doctor Who division) is abuzz over the announcement that cussy Caledonian Peter Capaldi has been cast as the twelfth incarnation of the Doctor. Capaldi will surely bring a new energy to the venerable British sci-fi institution — the show is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year — and at 55 years of age, with a portfolio of morally ambiguous characters on his rÁ©sumÁ©, promises a hard-edged take on a property that has, under the direction of showrunner Steven Moffat, trended increasingly warm and fuzzy.

Now, geeks are a contentious lot, and any possible casting choice was bound to be a disappointment to someone — especially to people (your own Old Professor among them) who feel that if the immortal Doctor can regenerate into any form, then there is no reason why he cannot incarnate as a woman, or a person of color. Science fiction is a literature of infinite possibilities, and to celebrate the casting of a white man in his 50s to take over the role from a white man in his 30s as some kind of visionary stroke seems to me unfairly limiting. It’s like the proverbial honky-tonk band boasting that they play both kinds of music, country and western — a distinction without a difference.

In the aftermath of the announcement, there’s been the usual round of media thumbsucking and demographic dissection: Will teenage Who fangirls want to watch a gross old man like Foulmouth MacSwearykilt? Would audiences ever accept a female Doctor? A lot of this has just been the usual fannish griping, easy enough to disregard. But there have been a couple of tidbits to emerge from the noise that leave me with a nasty prickly feeling — items having less to do with the casting of Capaldi than with an all-too-prevalent attitude of contempt for the audience.

The first was in an old blog post from writer Neil Gaiman, recounting his experience writing for Doctor Who. As Gaiman tells the story, Moffat responded to a particularly complex bit of plotting by telling him, ”Look, you understand that, and I understand that, but we’re Science Fiction people. The other 100% of the audience may not get it.”

On the subject of gender-blind casting, Moffat offered this gem: ”It’s absolutely narratively possible [that the Doctor could be a woman] and when it’s the right decision, maybe we’ll do it. [But] I didn’t feel enough people wanted it. Oddly enough, most people who said they were dead against it — and I know I’ll get into trouble for saying this — were women!”

Then a wholly unrelated story about the much-anticipated sci-fi thriller Snowpiercer, an international production directed by Bong Joon-Hoo. Snowpiercer has been getting good buzz abroad — but the film’s American distributor, the Weinstein Company, has announced that the film will be recut for its US release, losing 20 minutes of character beats and gaining an explanatory voice-over. According to English film writer Tony Rayns, ”[Harvey Weinstein’s people] have told Bong that their aim is to make sure the film ‘will be understood by audiences in Iowa … and Oklahoma.”

Do you hear that, folks? They think you’re stupid. Steven Moffat, in his wisdom, thinks that you won’t be able to wrap your head around his Big Ideas, that your tiny brain can’t handle the sight of an alien authority figure in an A-line skirt and sensible flats. Harvey Weinstein thinks you need the premise of this SF action piece spelled out for you at the start of the story.

This belief in the fundamental simplemindedness of audiences, especially American audiences, has become an article of faith among creatives and moneymen — and among far too many critics. Every brain-dead gross-out comedy that wins its opening weekend, every hacky sequel or remake that gets greenlit, every smart, innovative picture that underperforms at the box office is cited as evidence that audiences don’t want quality, don’t want originality. What audiences want, we are told, is to switch off their brains and for two hours and enjoy the company of familiar personalities. Audiences don’t want to work too hard; they want movies that arrive pre-digested — movies that, essentially, watch themselves.

That’s bullshit, of course.

What audiences want — what audiences have always wanted — is to be entertained; and if creators can deliver that, audiences have proven again and again that they are willing to put in a little effort to meet them halfway. Quentin Tarantino, Christopher Nolan, Ridley Scott, Ang Lee, Martin Scorsese — these are all filmmakers whose massive success has been dependent on the audience’s willingness to learn how to watch their films as they go along.

Television audiences, in particular, have proved receptive to works that both reward and demand close attention, be it Mad Men or The Wire or The Sopranos, Arrested Development or Adventure Time, Hannibal, The Venture Brothers, or even Community. Even when such shows lose their audiences, as in the later seasons of Lost or The X-Files, it’s less a function of their unrepentant complexity than of a simple failure to remain entertaining. A prime example of uncompromising sci-fi entertainment has just been released on US DVD.

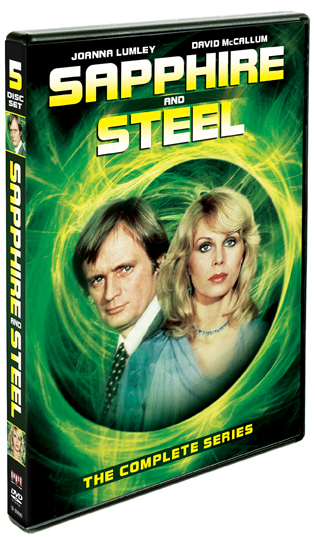

The five-disc Sapphire & Steel set, out this month from Shout! Factory, collects all 34 episodes of the British series, which ran on the independent ITV network between 1979 and 1982. More than 30 years on, Sapphire & Steel, created and mostly written by Peter Hammond, remains an object of fascination for its rejection of easy answers, its steadfast refusal to explain itself.

The title characters — played by Joanna Lumley and David McCallum, respectively — are mysterious figures who appear from out of nowhere to investigate anomalies in the timestream. But Doctor Who this ain’t. Sapphire and Steel are clearly not entirely human, but neither are they friendly Time Lords. She has some psychic sensitivity and a limited ability to wind back time by a few minutes; he has power over ambient temperature; and the two are telepathically linked.

And that’s about all we ever learn about Sapphire and Steel — about their relationship, about the authority that assigns them their missions, even about the exact nature of their enemies. The famous opening sequence is the closest we get to an explanation…

Plainly, this is not a show that will be spoon-feeding you vital story information. You will be dropped in at the deep end and will be expected to find your feet right quick — and the show, like the title characters, seems likely to snap at you if you can’t keep up.

Because Sapphire & Steel is anything but warm and fuzzy. McCallum’s Steel, in particular, seems to have little use for the humans under his protection; he is brusque, impatient, condescending. As Sapphire, Lumley is a marginally warmer presence, but it’s the difference between dry ice and snow.

Both of them act up a storm — perhaps surprisingly, given that Sapphire & Steel came during a rough patch in their respective careers. Lumley, former model and Bond girl, would reinvent herself in the 90s as a comedienne, but in 1979 she was coming off a reboot of The Avengers that had drawn mixed reviews. McCallum’s success with The Man From UNCLE had left him typecast, struggling through a string of failed series and B-movies; God knows how he must have felt about headlining a low-budget kiddie show, but he channels his heavy-browed surliness into a commanding performance, playing Steel on a note of constantly-simmering anger.

About that budget: It was low. Sapphire & Steel was shot cheaply on video, and each of its six serialized storylines used only a single location — a country house, an abandoned railway hotel, a disused service station. The supporting casts were kept small. But the show worked brilliantly within its limitations, turning them to strengths. The visual effects are simple but effective, as is the sparsely-orchestrated music. The lighting design is noticeably good, maintaining a gloomy, oppressive atmosphere throughout. And atmosphere is what Sapphire & Steel does best. Hammond created the show after spending the night in a purportedly haunted house, and Sapphire & Steel succeeds at evoking that experience. The single location, the looming shadows, the methodical pacing — all conspire to make the viewer, like the characters, feel anxious and trapped.

And a happy ending is by no means guaranteed. The malevolent forces that dwell outside of Time — or perhaps the malevolent intelligence of Time itself — cannot always be defeated. Victory may come with a terrible cost; Steel will not scruple to sacrifice individual lives for the greater good. And the series ends on an ambiguous note, with our heroes trapped in a time loop with no apparent means of escape.

It’s dark, unsettling stuff — thoughtful, moody, wonderfully eerie. Because the dark forces gain access to the timestream via human souls, Sapphire & Steel becomes, in part, an interrogation of nostalgia. The past is always lurking, always seeking to bleed through into the present. A nursery rhyme, an old photograph, a popular song from days gone by — any of these can make a crack in Time through which evil can enter the universe.

And here’s the thing: it’s absolutely gripping. McCallum and Lumley are fantastic; the supporting characters are well-drawn and beautifully-acted; and the mysteries pull you right along. Without telling you a single thing that you don’t absolutely need to know — indeed, by withholding some information you do need to know — Hammond keeps the situations nerve-janglingly tense. Sapphire & Steel is compulsive viewing, and wildly entertaining. And though it is not dumbed-down, it never feels inaccessible. The feeling of being in over your head, grappling with forces and concepts that you cannot fully comprehend, is essential to the viewing experience.

And here’s the thing: it’s absolutely gripping. McCallum and Lumley are fantastic; the supporting characters are well-drawn and beautifully-acted; and the mysteries pull you right along. Without telling you a single thing that you don’t absolutely need to know — indeed, by withholding some information you do need to know — Hammond keeps the situations nerve-janglingly tense. Sapphire & Steel is compulsive viewing, and wildly entertaining. And though it is not dumbed-down, it never feels inaccessible. The feeling of being in over your head, grappling with forces and concepts that you cannot fully comprehend, is essential to the viewing experience.

Look. Obviously, in any given audience drawn from a broad spectrum, there will be some dummies. It’s unfortunate, but it is a given. Not everybody’s light will burn with the same brightness, and there will inevitably be some folks in the crowd who can’t handle unfamiliar ideas or innovative storytelling. But that doesn’t mean that entertainment should, by default, cater to those people. It doesn’t mean that smart entertainment should perforce be a specialty product.

Every first-hand account of filmmaking I’ve ever read indicates that the industry is driven by a fear of excluding any viewer. It’s all right if you dislike a film, but it is a catastrophe if you do not understand it. This thinking needs to change, because it fundamentally misrepresents how people relate to their entertainment.

Newspapers are famously written on a fourth-grade reading level, because they are primarily vehicles for information; people read them because they need to. But audiences have different standards when they read for enjoyment. They will follow the turns of nonstandard syntax for the sheer pleasure of a well-turned sentence. They will regard the narrative of an unreliable narrator with appropriate skepticism. They will allow for the possibility of irony, for words not meaning precisely what they say. They will even, sometimes, turn to a dictionary when they encounter a word they do not already know. They are not reading to learn; but they are learning as they read — learning the rules under which they are to engage the very book they are reading. If you only ever read newspapers, and never read literary fiction, than you might never learn those essential decoding skills. And that would be a pity, because you would be locking yourself out of a world of entertainment.

TV and movies, though, seem to be stuck on that fourth-grade level of comprehension, with everything safe and familiar and immediately-graspable. Viewers are not expected to possess, nor are they encouraged to develop, any kind of advanced viewing faculties. And that is more than a pity: it is an active disservice to the viewing public. That a sharp, risky show like Sapphire & Steel still has a devoted audience after 30+ years something curious, something that mainstream filmmakers have all but forgotten: If you make the difficult entertaining, viewers will raise their game to appreciate it.

There are wise pleasures for the wise, and simple pleasures for the simple — but exposure to wise pleasures can actually bring wisdom to the simple. That’s not exclusionary thinking; that’s a way to grow your audience. In fact, in the end, it’s probably the only way.

Comments