And so we come, by the turning of the year, to the end of Shrovetide and the beginning of the Christian liturgical calendar. When I was a choir director, these three days of Easter were my favorite time of year. This is the time when Christendom enters its annual long dark night of the soul, and the rites of the Triduum still play out like a ritual drama. When programming music for Maundy Thursday and Good Friday services, I favored stark, direct songs — old folk hymns like ”When Jesus Wept, the Falling Tear” (sung here by Waterson Carthy) and ”What Wondrous Love Is This.”

The Passion narrative packs quite enough punch without slathering on the cheap pathos, and those rough old English tunes are sturdy things — tragic without shading into melodrama. If you’re thinking that it would be a tall order for any rock n’ roll song to capture that mingled mood of heartbreak and solemn awe, you’d be right. And if you’re thinking that Irish bombast-mongers U2 are unlikely candidates to pull it off, you’d be two for two. And yet their 1991 album track ”Until the End of the World” is a real thing, and it makes fools of us.

Now, this record came out more the twenty years ago, and I suppose it’s no longer esoteric knowledge that ”Until the End of the World” is written as a monologue, addressed to Jesus, from the perspective of the betrayer Judas Iscariot. (If you’re one of the few people who didn’t know this, congratulations! You’ve already learned your fun fact for the day, and can stop reading this column right now.) Catholic author and educator Stephen Catanzarite uses it as a starting point for his monograph on Achtung Baby, which aims to uncover a buried theological narrative running through the album as a whole.

The goal of Christian practice is to find room for the teachings of Jesus in our lives. But to really understand the betrayal, we need to understand the importance of the man from Nazareth in His own time and place — and to understand the actions of Judas in that same context. And it’s less a religious context than a political one.

Jesus and His disciples lived and died under military occupation. First-century Judea was a province of Rome. There was a local monarchy — King Herod Agrippa was ostensibly the head of state — but his was a puppet government; real power rested with the Roman provincial governor, or prefect. In the days of Jesus, this was a man named Pontius Pilate. (You may have heard of him.)

As always happens when one nation conquers another, petty local rivalries were absorbed into the larger conflict, and there were factions among the native Judean population who found ways to profit from the situation. When the Pharisees — a sort of cross between a political party and a theological movement — publicly backed the rule of Herod, and thus of Rome, they became the dominant force in Jewish religious and cultural life in the region, and rival factions — the conservative, aristocratic Sadducees and the radical ascetic Essenes — fell from favor.

As always happens when one nation conquers another, petty local rivalries were absorbed into the larger conflict, and there were factions among the native Judean population who found ways to profit from the situation. When the Pharisees — a sort of cross between a political party and a theological movement — publicly backed the rule of Herod, and thus of Rome, they became the dominant force in Jewish religious and cultural life in the region, and rival factions — the conservative, aristocratic Sadducees and the radical ascetic Essenes — fell from favor.

For the everyday people of Judea, though, the Roman occupation was a raw deal, and a lot of folks regarded Herod and the Pharisees as sell-outs, traitors, and quislings. The Zealots were an underground guerrilla movement opposed to Roman rule. They advocated for an armed rebellion against the oppressors, and undertook campaigns of vandalism and sabotage to undermine the occupation; some would even kidnap or murder members of the Roman and Greek minority populations.

So when Jesus came along, and the word got out that He might be the Messiah, the legendary figure who would lead the Jewish people to freedom — well. Is it any wonder people got the wrong idea?

Despite Jesus’ protestations that His kingdom was not of this world, the Roman authorities were understandably worried that He might incite an uprising. Their Judean collaborators — Herod and the Pharasaical religious establishment who supported him — didn’t want to give up their sweet deal. Even among those who opposed the status quo, Jesus found remarkably little support. Some of the Zealots had an interest in Him early on, but became disillusioned when He kept banging on about turning the other cheek and rendering unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s. Even some of Jesus’ own disciples urged Him to call down the wrath of God on the occupiers; clearly, His brand of revolution — a revolution in the head, a revolution of the heart — was a tough sell in this politically charged climate.

So what, exactly, led Judas Iscariot to betray the Son of Man with a kiss — and then to regret it so bitterly that he hanged himself? (Or that he “burst asunder, so that his bowels gushed out,” depending on whether you’re reading the Gospel of Mark of the Acts of the Apostles.)

It’s hard to say, because we know so little about Judas himself. We’re not even sure what ”Iscariot” means. It may be a Hebrew descriptor meaning that Judas came from the town of Kerioth, or it may derive from the Aramaic root-word for ”red,” indicating that he was a ginger. (Harvey Keitel played him as a redhead in Martin Scorsese’s film of The Last Temptation of Christ.) Or it may come from the Latin sicarius, or ”dagger-man,” marking Judas as a member of a terrorist offshoot of the Zealot movement, a cadre of assassins who preyed upon Roman occupiers and Jewish collaborators alike, cutting them down in the very streets.

It’s hard to say, because we know so little about Judas himself. We’re not even sure what ”Iscariot” means. It may be a Hebrew descriptor meaning that Judas came from the town of Kerioth, or it may derive from the Aramaic root-word for ”red,” indicating that he was a ginger. (Harvey Keitel played him as a redhead in Martin Scorsese’s film of The Last Temptation of Christ.) Or it may come from the Latin sicarius, or ”dagger-man,” marking Judas as a member of a terrorist offshoot of the Zealot movement, a cadre of assassins who preyed upon Roman occupiers and Jewish collaborators alike, cutting them down in the very streets.

Given these possibilities, and the political complexities of the time, why would Judas sell out the man that he gave up his home and family to follow? The Judas of the U2 song, as interpreted by Catanzarite, is a jaded nihilist, betraying his best friend for lack of anything better to do, prostituting himself to the Romans for a laugh — and for the money. The Gospel of John implies that Judas saw discipleship as a get-rich-quick scheme; he handled the disciples’ finances, and was skimming off the top. That ”thirty pieces of silver” would have been about three month’s wages for a laborer. Not a fortune, but not chump change, either. But we should take the stated amount with a grain of salt; Exodus 21:32 names thirty silver shekels as the price of a single slave, and with that in mind the use of that figure in Matthew’s gospel — written for a Jewish audience, and packed with allusions to Old Testament scripture — seems blatantly symbolic.

But if we take it as given that Judas was member of the Judean resistance — a Zealot, or even one of the sicarii — then the picture changes. Perhaps, like many Zealots, he had been attracted to Jesus’ ministry in the mistaken belief that, eventually, He would drop all the peace-and-love jive and get down to knocking some Roman skulls. But even if Judas were a disappointed Zealot, why would he turn Jesus over to those same authorities whom he himself despised?

But if we take it as given that Judas was member of the Judean resistance — a Zealot, or even one of the sicarii — then the picture changes. Perhaps, like many Zealots, he had been attracted to Jesus’ ministry in the mistaken belief that, eventually, He would drop all the peace-and-love jive and get down to knocking some Roman skulls. But even if Judas were a disappointed Zealot, why would he turn Jesus over to those same authorities whom he himself despised?

Or maybe Judas never intended for Jesus to die. Maybe he truly believed that Jesus was the Messiah, and figured that He would never allow Himself to be crucified. Having grown tired of waiting for Jesus to commence with the smiting, maybe Judas figured that he could force the Messiah’s hand; if He were put into a life-threatening situation, would He not surely call down the fire from Heaven in His own defense?

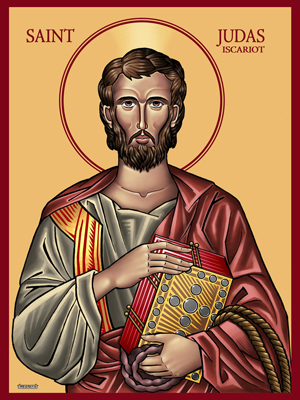

Judas pictured as a Saint, in the icon style of the Orthodox churches. The Gospel book he carries is encrusted in silver coins making the shape of the Cross; he carries a rope and his bowels are spilling out, symbolizing the varying accounts of his death.

Carrying on in this vein, imagine that Judas did not know from the start that Jesus would be condemned to death. He had, in modern parlance, no priors, and there were all kinds of self-proclaimed prophets running around Jerusalem in those days. Under ordinary circumstances, He might simply have been flogged and released. It’s possible that, in a perverse way, Judas thought he had Jesus’ best interests at heart. In this reading, Judas feared that Jesus’ growing public profile, already an irritant to the local Pharisees, would soon grow out of control and bring the wrath of Rome crashing down, possibly with terrible consequences for all of Judea. Perhaps Judas hoped that Jesus might be ”scared straight” by His ordeal, and scale back His public ministry. After all, a whipping, however horrific, is preferable to death. This would explain Judas’ awful remorse when he learns that Jesus is to be crucified, and his attempts to give back the money.

All of these scenarios presuppose that Judas, in some fundamental way, misunderstood the message and the mission of the Christ — that he mistakenly thought that the Chosen One would come in triumph, to lead His people to victory in arms, to destroy the heathen invader with fire and sword. But there is one last reading of the betrayal story — the strangest, the most radical, and the one that seems to me the most likely to be true.

Suppose that Judas, of all Jesus’ disciples, was the one who truly did understand His mission, who understood that it was necessary that the Lamb of God should be sacrificed, that He should be humiliated and tortured and killed. Who understood that only by His suffering and death could Jesus redeem mankind. Who was the only one Jesus could trust to do what was necessary to bring the mission to fulfillment. Who would deliver his friend to his destiny — who would assure the deliverance of all humanity — by making sure that Jesus was arrested and tried. Who would be strong for Jesus at a time when Jesus could not be strong for Himself.

In The Last Temptation of Christ, novelist Nikos Kazantzakis (and filmmaker Scorsese) literalize this by making Judas into the conscience of Jesus, who appears to Him when the devil tempts Him with a vision of the life He could have had, and urges Him to accept His cross:

[youtube id=”E1ulq07LIMM#t=378s” width=”600″ height=”350″]This Judas is the bravest and truest of Jesus’ disciples. This Judas is the secret tragic hero of the Gospels, dark mirror-twin of the Saviour, taking upon himself the burden of damnation in committing the unforgivable sin, sacrificing his own immortal soul as surely as Jesus sacrificed His own body, and for the same cause — to purchase, by his suffering, the salvation of all the world.

Something to talk about, anyway, if there’s a lull in the conversation around the Easter dinner table. Or you could just argue about which version of ”Until the End of the World” is better.

Comments