I’ve been catching up on the Entertainment Geekly podcast this week (which is my own damned problem, I suppose), and I was struck by an odd conversational turn during a discussion of Marvel Comics: The Untold Story. The book’s author, Sean Howe, was talking about how he came to comics as a teenager via The Uncanny X-Men, specifically writer Chris Claremont’s long tenure on the title.

That sounds familiar. Since its dÁ©but in the early 1960s, the X-Men franchise has been the gateway drug for generations of adolescent readers. Indeed, it might just be the platonic ideal of teen-friendly serial fiction, especially when written by Claremont. Not only did he serve up a devil’s brew of soap-opera turns and reversals, dysfunctional family dynamics, sci-fi trippiness, and old-fashioned melodrama — in his stories of superhuman mutants, hated and rejected by a world that fears them, there lurked an all-purpose metaphor for adolescent alienation: What teenager, gazing at his own acne-riddled face in the mirror, has not felt like a misunderstood freak?

Chris Claremont worked with a number of different collaborators during his time on the book, and Howe made passing reference to artist Paul Smith’s 10-issue run as ”definitive.” Podcast co-host Jeff Jensen took exception to that, pointing to an earlier period — the time when the book was relaunched with a new cast, under the artistic stewardship of Dave Cockrum — as ”definitive.” Said period, not-so-coincidentally, is about the time when Jeff Jensen started reading Uncanny X-Men. The dispute was quickly brushed aside, though, with an unspoken assumption that such questions are entirely personal.

This is a curiously widespread notion in fandom circles; that the creative highpoint of a long-running serial franchise fiction can — and indeed should — be defined subjectively, that any given introductory experience with the property becomes the de facto yardstick against which all opther periods are judged. That your estimation of A New Hope vs. The Phantom Menace, or your chosen incarnation of the Doctor, or the Original Series vs. the Next Generation or even (God help you) Voyager, will depend wholly on where you came in.

This is a curiously widespread notion in fandom circles; that the creative highpoint of a long-running serial franchise fiction can — and indeed should — be defined subjectively, that any given introductory experience with the property becomes the de facto yardstick against which all opther periods are judged. That your estimation of A New Hope vs. The Phantom Menace, or your chosen incarnation of the Doctor, or the Original Series vs. the Next Generation or even (God help you) Voyager, will depend wholly on where you came in.

This attitude presents difficulties for the critic, because underpinning it is the tacit notion that distinctions of quality are illusory; that there are no firm bases for judging anything as ”better” or ”worse,” only as ”favorite” or ”least favorite.” In other words, one must assume that the franchise remains aesthetically static throughout — that its quality in absolute terms never varies significantly from a given baseline. There’s a problem right there… because, sadly, not all creators are created equal, and the quality of the product is bound to vary with the skill of the craftsman. Even when a franchise is subject to the singular creative vision of a lone individual — as with a TV showrunner or, in the case of Uncanny in its heyday, a single nominal writer — the collaborative nature of franchise storytelling entails a degree of compromise.

Indeed, the creative practices in use at Marvel Comics at the time guaranteed it. While Chris Claremont was the sole credited writer for Uncanny, the Marvel production style — as Howe outlines in The Untold Story — gave great leeway to the artists, not just to select storytelling strategies, but actually to dictate plot and characters. The ”Marvel Method,” in theory, keeps artists invested in the story by giving them more freedom to draw what they like. In practice, the artist becomes the co-plotter — indeed, penciller John Byrne was credited as such during the latter part of his Uncanny run — taking a vital hand in shaping the direction of the franchise.

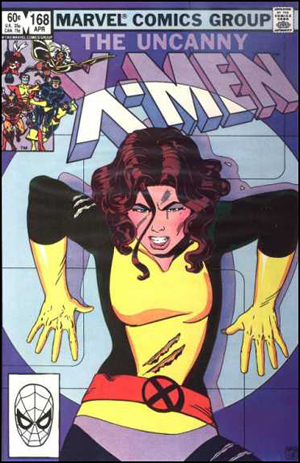

Different artists have different ambitions. When I started reading Uncanny, during the back end of Byrne’s tenure, he and Claremont were introducing new concepts to the Marvel Universe at a breakneck pace — concepts that continue to reverberate through the X-Men franchise, thirty years on. Within the twelve issues of Uncanny bearing a 1980 cover date, we were introduced to the Hellfire Club, Kitty Pryde, and the Dazzler; witnessed the metamorphosis of Jean Grey into the Dark Phoenix, and her subsequent tragic death; got our first look at Wolverine’s redesigned costume; and, for good measure, kicked off the time-travel epic ”Days of Future Past.” Not a bad year’s work.

After Byrne’s departure in early 1981, the art chores passed back to penciller Dave Cockrum, who had helped relaunch the title back in 1975. Cockrum’s return was a letdown. At the time, I attributed it to the art — Cockrum’s figure work had grown stiff, and Joe Rubinstein’s soft-brushed finishes couldn’t have looked more different from the work that Byrne had produced with inker Terry Austin, which was as tight, as hard, and as bright as a diamond — but the changes to the book were more than superficial.

Under Cockrum’s custody, the X-Men squared off with Marvel mainstays like Dr. Doom, Magneto, and the mutant-hunting Sentinels. Fan favorites Havok and Polaris were brought back, as were the Cockrum-created space pirates the Starjammers. There was a retread of the Dark Phoenix storyline, as Storm went (temporarily) mad with power (check out that shameless cover blurb: ”We Did It Before … Dare We Do it Again?”). There was even a grand space-opera storyline to end his second go-round, just as the eight-issue ”Phoenix Saga” had ended his first. In short: After the sustained invention of the Byrne years, Cockrum’s return played like a Greatest Hits record.

Fair play to Cockrum, who died in 2006: He was drawing the kind of comics that he wanted to read. As a fan and scholar of comics long before he turned pro, he retained a deep nostalgic affection for the characters. But that very affection pointed toward the franchise’s eventual descent into self-parody. Spurred on by Cockrum — and in the absence of new Grand Crazy Ideas upon which to build his stories — Chris Claremont’s writing turned inward, towards an obsessive examination of the team dynamic. His scripts had always found room for poignant character beats, but now the stories ground to a halt as page upon page was devoted to exploring how the various X-Men felt about each other. Whimsy levels grew toxically high: female characters went shopping together; events of past issues were recast as fairy tales; Kitty had a new hideous costume every month. All Claremont’s worst tics — which would only grow worse in later years — were on full display.

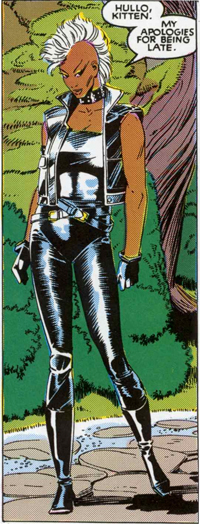

After the disappointment of Cockrum’s second residency, Paul Smith came in like a breath of fresh air. It took him a couple of issues to find his feet — the result, most likely, of being tasked with wrapping up Cockrum’s final storyline — but he was soon reinventing the book. Some of the narrative innovations of his run — adding the reformed villain Rogue to the team, the introduction of the sewer-dwelling mutant outcasts the Morlocks — had staying power; others, like Storm’s leather-and-mohawk makeover, did not. But Smith’s primary innovations were stylistic.

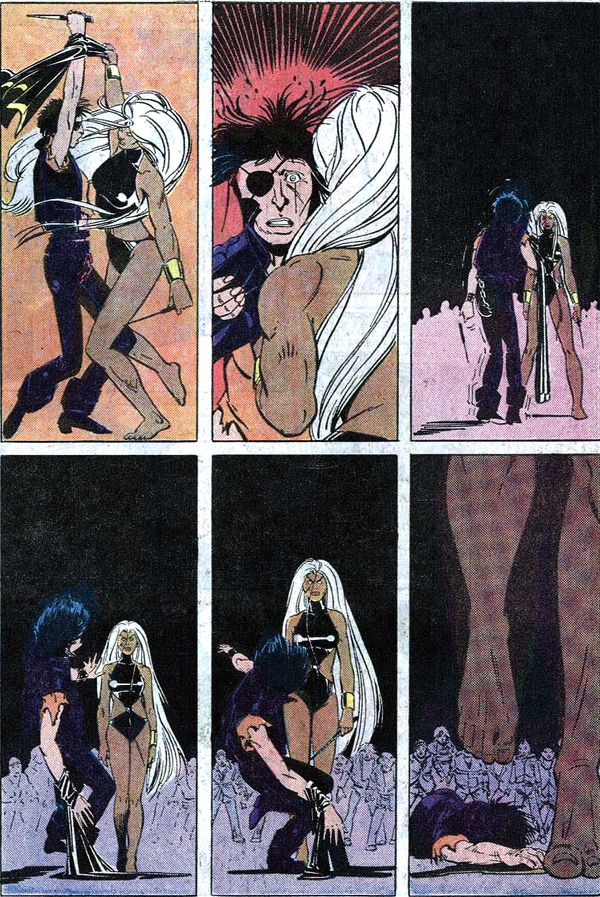

From his bow in January 1983, Smith’s linework was clean and uncluttered, but less in the John Byrne / Neal Adams mode than in the Franco-Belgian ligne claire style. His storytelling, too, has a Eurocomic sensibility. Look at this famous page, the climax of the first Morlocks story. Even in this crappy scan, it’s a master class in comics storytelling — brutal violence in a series of frozen moments, the very stillness of the images making the impact more visceral. (This was three years before Dave Gibbons perfected the technique in Watchmen.)

Even better, Smith’s visuals pushed Claremont’s writing to new heights. Sometimes the Marvel Method left artists and writers at cross-purposes; Such was the case with Uncanny’s sister book The New Mutants, which found Claremont using acres of captions in a desperate struggle to keep Bill Sienkiewicz’s art — surreal, perverse, sometimes verging into inky abstraction — grounded in some kind of narrative. But Smith’s cinematic style was more immediately sympatico with Claremont, and the two of them could switch on a dime from screwball comedy to film noir atmospherics (one issue was even entitled ”To Have and Have Not“) that transcended the usual soapy melodrama for moments of real pathos.

Uncanny X-Men had long been glorious pop, but under Paul Smith it became unashamedly arty. What makes Smith’s run fondly remembered 30 years later, despite its brevity, what makes it definitive — what makes any run definitive — is its ambition. His ten issues are consciously breaking new narrative ground, pushing the artform, raising the bar.

That’s the true measure of quality, and it doesn’t matter when you started reading the book. It used to be that the Latin motto De gustibus non est disputandum — ”There is no arguing with taste” — was an insult, a way of dismissing the undeserved success of crappy art. But in fandom, it has become a rallying cry, a shield to protect one’s treasured garbage from the ravages of artistic judgment.

The guiding principle of any kind of art criticism is to answer two questions: What is this art setting out to do? and How well does it succeed in doing it? There’s a third question, though, that often goes unspoken, and here’s where it gets controversial: Is it worth doing in the first place? The answer is open to personal preference, but in general the loftier the goal, the more credit the artist gets for succeeding. If your aim is to introduce oblique European-style storytelling to American superhero comics, I’m going to rate you higher than if you simply want to produce familiar, entertaining stories about the characters you love.

For a lot of fans, of course, the latter is sufficient. Given the never-ending serial nature of comics, the fanbase has become invested in those characters, and has grown accustomed to accepting a certain degree of mediocrity so long as they can keep their monthly appointment with Wolverine on time. If the creative team is rewriting the rules of comics in the process, so much the better — but shipping the books on time is still Job One. Quality is secondary; one Wolverine book by anybody is as good as another by someone else, in the end.

The publishers are well aware of that theory of aesthetic stasis — in fact, they have historically counted on it. Throughout the Terrible 90s, there was little motivation for franchise comics to do anything but keep turning product out on time and in bulk, on the assumption that fans would keep buying em. The books themselves only needed to be pretty good in the aggregate — sometimes better, sometimes worse, so long as it all evened out — the better to propagate the myth that quality is inseparable from personal preference, a function of nostalgia rather than an inherent property.

Thankfully, the creative landscape has shifted again, and in some places writers and artists of great talent are being hired and rewarded specifically for their individual, ambitious takes on corporate franchises. That’s the kind of thing that attracts new readers. In the end, though, it might not be enough to save a dying comics industry that for too long has bet on the wrong business models. Leveraging its long-term health for a series of short-term cash grabs. That’s a whole nother essay, for another time — but there’s only life in the old genre for as long as it keeps moving forward. You don’t get to be ”definitive” simply by exemplifying the artform as it stands, month after month. You’ve got to advance it. To define is to re-define.

Comments