When does a girl become a woman? Is it a biological or a psychological phenomenon? Likely a combination. Important signposts along the road: First bra. Actually needing one’s first bra. Menstruation. First love. Starting to shave one’s legs andÁ¢€¦other things. First sex. First orgasm. (Note that those last two don’t necessarily go together.) Personally, I feel that I reached such a milestone on my thirteenth birthday, but not because of my age Á¢€” because of a book.

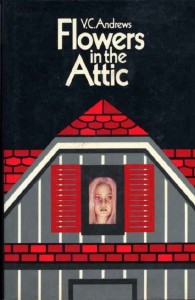

I remember opening my presents that spring morning. There may have been some now-forgotten items of clothing among them, but the other stuff is still vivid in my mind. First, Whitney Houston’s debut album (on vinyl). Then I unwrapped a paperback, thick, with a spooky cover: a girl’s face, looking like she was holding a flashlight under her chin in a dark room. Flowers in the Attic by V.C. Andrews. Thanks, Mom and Dad. They wouldn’t let me go to R-rated movies but I could read anything I wanted. I knew I would start reading on the bus on the way to school. Soon, I would be sucked into a literary obsession, lost in a world of Southern gothic psychodrama from which I would never completely return.

In a nutshell (a sick, sick nutshell), Flowers in the Attic is a late-’70s bestseller about a newly pubescent girl who, along with her three siblings, is hidden in the attic of her grandparents’ mansion so her mother can collect an inheritance. For three years, these extremely blond children are tortured by their bat-shit crazy grandma, who whips them, starves them and poisons them while telling them they are the spawn of Satan. Deprived of sunshine and fresh air, the youngest two fail to thrive, leaving them with little kid bodies and big kid heads. Meanwhile, the oldest girl and boy get super horny andÁ¢€¦well, you can imagine where that goes. After tearing through the entire 400 pages in about three days, it was off to the bookstore to buy the next one in the series.

Oh yeah, it’s a series.

Over the years, this sad quartet and their progeny experience everything from miscarriages to sexual abuse to gangrene to arson, with lots of dialogue like “Damn you to hell, Mother!” punctuating the madness. And to think I had been wary of Ms. Andrews’ oeuvre at first because the cover art gave me the willies. (Then again, I was the kind of kid who was terrified by movies like Gremlins.) I zipped through all seven of her novels in a matter of weeks. So did a number of my friends, to whom I would pass on my copies; they would show up at school every day with glassy eyes from having stayed up too late reading about crazy hillbillies selling their kids and disemboweling hamsters (Heaven) or a woman copulating with her husband on her own grave (My Sweet Audrina). We were (mostly) good girls fixated on (very) bad people.

With all this drama occupying my mind, I’m not sure how I managed to graduate from seventh grade. It was all V.C. Andrews, all the time. I started writing a Flowers in the Attic screenplay. I made mix tapes for the soundtrack. Madonna’s “Live to Tell” seemed especially apt, so I used it as the basis for a short ballet, choreographed and performed by myself and two close friends for our class talent show. That summer at camp, while other girls were making lanyards and sneaking off to pull pranks in the middle of the night, I was spreading the good word about V.C. Andrews. “Isn’t that the one where they’re all going bonkers and raping each other?” my skinny British counselor sneered. I was undeterred by her dismissive Eurotrash attitude. At the end of the summer, I had not, sadly, learned how to double-dutch, but I was presented with “The V.C. Andrews Award” for my work as the self-appointed expert of mass market paperback puberty horror.

As deep as it may burrow into our tender souls, adolescent obsession isn’t built to last. Two tragic events brought me, kicking and screaming, back to a world not populated with lecherous uncles and homicidal half-sisters. First, V.C. Andrews died. Her publisher promptly hired a ghostwriter Á¢€” a former high school teacher, no less Á¢€” to complete books she had left unfinished and begin new ones under the Andrews name. I read a few, trying to recapture the feeling of the original novels, but they all seemed like fan-fic rather than the real deal. (Ironically, “V.C. Andrews” has published dozens upon dozens more books posthumously than she did while she was alive.) A year later, a film based on Flowers in the Attic was released. A fellow Andrews-freak joined me on a cold Saturday morning for the earliest showing. The movie should have been a slam dunk: I mean, how do you screw up a story jam-packed with Biblically-inspired violence and pastries sprinkled with arsenic?

They found a way. Everything was wrong. There’s such a fine line between over the top and overdone. I arrived at the theater expecting to see a psychotic old lady driving a pair of hot young people into an incestuous passion. But some genius at the no-name production company must have decided that the brother-sister coupling was no big deal, because when the lights came up, the most they had done was hug one another very tightly. It was as if Rhett Butler had turned to Scarlett and said, “Hasta la vista, baby,” or Rosebud had turned out to be a brand of chewing gum. Damn you to hell, Hollywood!

The world had gotten its hands on something important to me and millions of other sexually repressed, over-imaginative teen girls and spoiled it with their pathetic inability to appreciate its glorious filth. Like Cathy, the narrator and main character of Flowers in the Attic, I carried a burning desire for justice deep inside for years. Unlike her, I did not feel the need to seduce my mother’s husband to achieve it. My method of healing was far less gross and destructive: I wrote something. Specifically, I wrote an academic paper for a Master’s program, in which I linked Andrews’ novel to Medea, Grimm’s fairy tales, Jane Eyre, Freud’s theory of the uncanny, and oral contraception. Don’t be surprised if you see this paper published one day, in your favorite bi-annual women’s studies journal. There are a lot of us deep-thinking chicks out there, hanging out in the murky space between fear and fantasy.

Comments