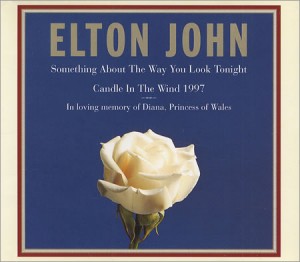

Creating a “song that kills” doesn’t necessarily mean putting out a song that kills your career, or puts you permanently out into One-Hit-Wonderland going forward. There is every possibility of having success after a release that gains massive notoriety and alters the world’s opinion of you. Take, as an example, Sir Elton John’s tribute to Diana, Princess of Wales with “Candle In The Wind 1997 (Goodbye England’s Rose).” I think few people would argue that John, and co-writer Bernie Taupin, haven’t suffered greatly since, but neither has their ongoing collaboration had quite the same shine since it.

We say these things knowing full well that the duo had been deeply ensconced in the Adult Contemporary world already. There wasn’t going to be another Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, no “The Bitch Is Back,” and not even an “I’m Still Standing.” So be it. But many saw the re-appropriation of Goodbye Yellow Brick Road‘s “Candle In The Wind” as a step too far, though most only admitted that later on. In the moment, at the remembrance of Diana and the temporary demise of the storybook myth that had adhered itself so thoroughly to her life, people seemed to lock onto the track. It was as if they believed in it hard enough, they could bring her back, as much as clapping very intensely and loudly could resurrect Peter Pan. It didn’t work.

We say these things knowing full well that the duo had been deeply ensconced in the Adult Contemporary world already. There wasn’t going to be another Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, no “The Bitch Is Back,” and not even an “I’m Still Standing.” So be it. But many saw the re-appropriation of Goodbye Yellow Brick Road‘s “Candle In The Wind” as a step too far, though most only admitted that later on. In the moment, at the remembrance of Diana and the temporary demise of the storybook myth that had adhered itself so thoroughly to her life, people seemed to lock onto the track. It was as if they believed in it hard enough, they could bring her back, as much as clapping very intensely and loudly could resurrect Peter Pan. It didn’t work.

In hindsight it is difficult to fathom the depths of Anglophilia that surrounded Diana. There was a lot more riding on her existence than the crown of England. In her post-marriage role she became an emissary for charities. She became a symbol, in abstract form, for asserting individuality over conformism. She rejected the mighty royal family, after all. She sired the future heirs to the throne, one of which is now integrated (trapped?) in the continuation of this sort of unfair fairytale narrative. Diana also was seen as a kind of trapped creature, yearning for freedom but always sniped at by hunters with cameras. It is no wonder that people briefly clung to “Candle In The Wind 1997” so completely. It is one of the best-selling singles of all time.

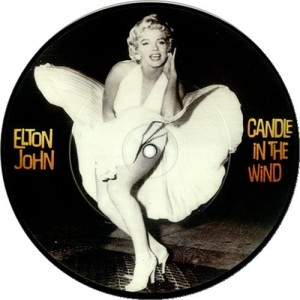

When Diana was well and truly departed and that reality sunk in, people started to take a closer listen. Unlike the original, an ode to Marilyn Monroe which was surprisingly even handed, the redux was notably heavy-handed. The original saw the protagonist as not just a victim but, perhaps, complicit in her ultimate victimization. It did not blame her, but it spoke of her humanity, her need for fame, and the price she paid to get it along with the constant dues she suffered for having it. Not so much with the remake.

One had to ask, if this was done by one of the preeminent musical collaborations of the day, could they not have done a unique track devoted solely to her? Why revise an older, fondly remembered song like so much reheating leftovers with some seasoned salt thrown in? Memory is fuzzy when looking back from 2014, or 1997, to the early 1970s. We think the original version was a hit off of its album. It wasn’t. It was actually never released as a single in the U.S., with that key slot paying major dividends when label MCA opted for “Bennie And The Jets” instead. “Candle In The Wind” didn’t become a hit until John’s live album much more than a decade later with the Melbourne Orchestra. Had “Candle In The Wind” remained a well-known deep track from the Seventies, it might not have been as much of a problem, but now it was fully engrained in the public recollection. (It occurs to me that many people think “Harmony” was a hit too. It was, in fact, another album track and a B-Side. Like I said, memory is fuzzy.)

One had to ask, if this was done by one of the preeminent musical collaborations of the day, could they not have done a unique track devoted solely to her? Why revise an older, fondly remembered song like so much reheating leftovers with some seasoned salt thrown in? Memory is fuzzy when looking back from 2014, or 1997, to the early 1970s. We think the original version was a hit off of its album. It wasn’t. It was actually never released as a single in the U.S., with that key slot paying major dividends when label MCA opted for “Bennie And The Jets” instead. “Candle In The Wind” didn’t become a hit until John’s live album much more than a decade later with the Melbourne Orchestra. Had “Candle In The Wind” remained a well-known deep track from the Seventies, it might not have been as much of a problem, but now it was fully engrained in the public recollection. (It occurs to me that many people think “Harmony” was a hit too. It was, in fact, another album track and a B-Side. Like I said, memory is fuzzy.)

The end effect was almost like a double-victimization of Marilyn Monroe. Here was this musical throne built in her honor, in a time the most sympathetic portrayal that had been offered of her, but almost without regard at the death of Diana, Norma Jean’s corpse was evicted from that throne and replaced. Again, this seems unnecessary for a musical team that produced a number one hit song every year for more than a decade, and sometimes multiple number ones per year. It seems lazy, to call it straight.

It didn’t go by unnoticed. It was either Saturday Night Live or MadTV that ran a parody commercial called “Elton John’s Tributes To Dead Celebrities” eulogizing a host of notables, each more outlandish than the last, with classic rock retrofitting. The tunes were turned into Weird Al Yankovic-styled parodies, and in the end, that’s sort of how “Candle In The Wind 1997” feels. I stress that it was never how it was meant. I guarantee that both Elton and Bernie were sincere, but sincerity cannot make a bad idea into a good idea.

Elton can still pull an audience. He is one of those few, rare artists from a long time ago that can still command premium ticket pricing. He is still an event. I have not been all that excited about his albums though. I’ve tried. People have stated Peachtree Road, The Captain and The Kid, and The Diving Board are returns to form, being more driven toward Elton’s earlier piano-driven opuses rather than his rock and roll side. While I will say the skin of these animals clearly exhibit those tendencies, the bones inside are brittle. It is a brittleness, and a schmaltziness, that did not begin with “Candle In The Wind 1997” but certainly was the peak moment of it. The real damage I feel that song did was that it showed this consummately capable team of songwriters, Elton and Bernie, as being too easily persuaded by good intentions linked with really bad ideas. Once that suggestion had been planted in the larger consciousness, it became hard to shake. You looked for fault, and when you found fault it only reinforced your purpose in looking in the first place.

Elton can still pull an audience. He is one of those few, rare artists from a long time ago that can still command premium ticket pricing. He is still an event. I have not been all that excited about his albums though. I’ve tried. People have stated Peachtree Road, The Captain and The Kid, and The Diving Board are returns to form, being more driven toward Elton’s earlier piano-driven opuses rather than his rock and roll side. While I will say the skin of these animals clearly exhibit those tendencies, the bones inside are brittle. It is a brittleness, and a schmaltziness, that did not begin with “Candle In The Wind 1997” but certainly was the peak moment of it. The real damage I feel that song did was that it showed this consummately capable team of songwriters, Elton and Bernie, as being too easily persuaded by good intentions linked with really bad ideas. Once that suggestion had been planted in the larger consciousness, it became hard to shake. You looked for fault, and when you found fault it only reinforced your purpose in looking in the first place.

“Candle In The Wind 1997” didn’t kill their careers, but it did kill that facade of instinctual infallibility. That may be just as detrimental.

P.S. “That’s What Friends Are For” was not written by John/Taupin, so even though it is more of a musical felon than “Goodbye England’s Rose,” Elton is only an accessory to that one.

Comments