If you think that today’s rappers have corned the market on sexual braggadocio, think again. While the current hip-hop stars may describe their amorous adventures in explicit detail, there’s a tradition of sexual one-upmanship that goes back to the blues songs of the 1920s, and probably before that.

Some say that “Sixty Minute Man” was the first rock and roll record. While there are always going to be differing opinions on that score, what is not in doubt is that Billy Ward and His Dominoes were one of the most successful vocal groups on the R&B scene in the 1950s. Ward himself was a musical prodigy. He was born in Savannah and following a stint in the Coast Guard, where he sang in the choir, Ward studied music at the Julliard School of Music in New York City. It was an experience that was extremely rare for a black person in those days.

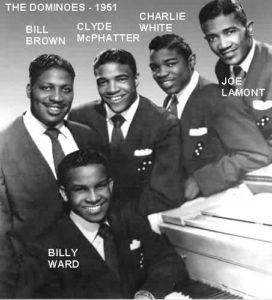

Ward was working as a vocal coach in New York when he met Rose Marks, who became his agent and his songwriting partner. The pair decided to form a vocal group, drawing the singers from among Ward’s students. At first, they were called the Cues, and Clyde McPhatter was chosen as the lead singer after he won a talent contest at the Apollo Theater. The other Cues were Charlie White, Joe Lamont, and Bill Brown. Ward played piano for the group and created their vocal arrangements.

The Cues made successful appearances at the Apollo, and on the Arthur Godfrey TV show. They were recommended to Ralph Bass of Federal Records, an imprint of the King label. When the label signed them, the Cues became the Dominoes. McPhatter sang lead on their first single for the label, “Do Something For Me,” which reached #6 on the R&B chart in early 1951.

Not long after that, the Dominoes released “Sixty Minute Man,” this time with bass singer Brown singing the lead vocal. Brown promised his lady 15 minutes of kissing, 15 minutes of teasing, and 15 minutes of squeezing, after which he would be “blowing his top.” Whew! Those sentiments were enough to take “Sixty Minute Man” to the top of the R&B chart, where it remained for 14 weeks and, crucially, crossed over to a spot on the Pop chart at #17. The groundbreaking blend of gospel, blues, and sex, apparently appealed to everyone, although in some quarters it was relegated to the ranks of novelty records.

Billy Ward and His Dominoes became bigger than contemporaries like the Five Keys and the Clovers. But Ward was a tough taskmaster and didn’t pay the Dominoes enough to make the discipline worthwhile for them. Jackie Wilson, who would replace McPhatter in 1953, said:

“Billy Ward was not an easy man to work for. He played piano and organ, could arrange, and he was a fine director and coach. He knew what he wanted, and you had to give it to him. And he was a strict disciplinarian. You better believe it! You paid a fine if you stepped out of line.”

Ward and Marks owned the Dominoes name, giving them the power to hire and fire at will. Meanwhile, McPhatter was barely making enough money to live on. “Whenever I’d get back on the block where everybody’d heard my records—half the time I couldn’t afford a Coca-Cola,” McPhatter said. Given the name of the group, many people thought that Ward was the lead singer, and sometimes he billed McPhatter as Clyde Ward so that people would think that he was Billy’s little brother.

The first two defections came in 1951 when White and Brown left to form the Checkers. They were replaced by James Van Loan and David McNeil, who had been in the Larks. Despite the lineup changes, the hits kept coming. Maybe Ward had a point. “Have Mercy” hit the top of the R&B chart in 1952 and enjoyed a 10-week stay at the top. The big departure came the following year when McPhatter decided that he had had enough and left the Dominoes to form his own group, which he called the Drifters.

That could have been a death blow for the Dominoes, but McPhatter’s replacement was Jackie Wilson, a vocal student of McPhatter’s. At around that time McNeil and Lamont left and were replaced by Milton Merle and Cliff Givens. The interchangeable parts continued to function successfully as records like “You Can’t Keep a Good Man Down” continued to find chart success, albeit not the same level of success as the McPhatter-led hits.

In 1954, the Dominoes moved first to Jubilee Records, and then to Decca. They had a nice-sized pop hit with “St. Therese of the Roses,” with Wilson singing lead. But that was about it for chart activity for the group. They soldiered on though, with more lineup changes, and when Elvis Presley saw the Dominoes in Las Vegas in 1956 he was so impressed by Wilson’s vocals on Otis Blackwell’s “Don’t Be Cruel” that he returned to Memphis and recorded it again, this time with the Million Dollar Quartet. Elvis always said that Wilson sang the song much better than he did, and he appreciated the Dominoes slower arrangement so much that he did an impersonation of it backed by Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, and Jerry Lee Lewis.

In 1957 Wilson left to begin his own legendary solo career. Enter another former-Lark, Gene Mumford. Another label change took the Dominoes to Liberty Records where they hit #13 on the Pop chart with “Star Dust.” Somehow, despite all of the changes, including the loss of two future superstars, there was still some gas in the Dominoes tank. Incidentally, “Star Dust” was one of the first multi-track recordings in rock and roll history, as well as one of the first to be mixed in true stereo. It was the Dominoes only million-seller, and their final big hit, although various Dominoes lineups continued recording and performing well into the 1960s.

Billy Ward and His Dominoes were elected to the Vocal Group Hall of Fame in 2006. They were a group that not only broke new ground musically but one that gave birth to the careers of two of the biggest stars, in McPhatter and Wilson, that soul music has ever seen.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OpQuNY3XFI0

Comments