Miss Christina drives a 944

Satisfaction oozes from her pores

She keeps rings on her fingers, marble on her floor

Cocaine in her dresser, bars on her door

She keeps her back against the wall

She keeps her back against the wall

So I say “Welcome to the boomtown

“Pick a habit, we got plenty to go around”:

It’s difficult to imagine a more unlikely first verse for a Top 40 song in 1986 — it was, after all, the year of El DeBarge’s “Who’s Johnny?” — and musically, the song’s creepshow synths and wobbly E-Bow were no less anomalous. Yet something about David & David’s “Welcome to the Boomtown” must have struck a chord with the people listening to pop radio, because it was a decent-sized hit; the duo found itself one of the most buzzworthy new artists of the year. It all flamed out spectacularly before they managed to even release a follow-up, and the David who went on to a solo career would discover an increasing lack of support — even hostility — from label bosses (not to mention an indifferent record-buying public).

But hey, things get a lot more interesting when everybody stops watching, and that makes the discography of David Baerwald pretty damn fascinating.

Boomtown (1986)

purchase this album (Amazon)

Baerwald set the pattern early — as in the first line of his first release — establishing right away the stuttering beat of his songwriting heart. His songs are littered with people who either never had a chance or pissed it all away. The streets are dark and dangerous, you can’t trust the cops, the wealthy are corrupt, and the government doesn’t give a fuck about you — yet somehow, impossibly, always, there is a beautiful glimmer of humanity. Sometimes even the hope for redemption. And his voice is the perfect vehicle: ragged; slippery of pitch; alternating between world-weary sigh and anguished howl. It’s postmodern Los Angeles as the Wild Wild West, and in many ways, he’s never altered that viewpoint.

Musically, Boomtown is a piece of the ’80s, although I think it holds up better than other albums of the period. The synths and drum machines are there, but you can tell they’re being used by guys who started using them because they were living in a one-bedroom apartment above a Mexican restaurant and couldn’t afford a full band setup, not because they wanted to sound like the latest Jellybean Benitez production. There’s a difference.

[youtube id=”gi7eprMlXnU” width=”600″ height=”350″] [youtube id=”ikPBffZz1HQ” width=”600″ height=”350″]

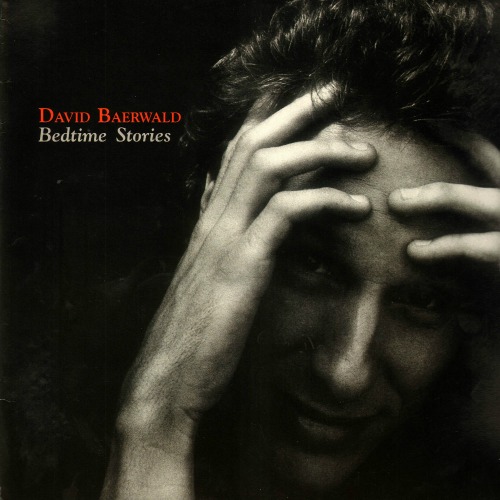

Bedtime Stories (1990)

purchase this album (Amazon)

Before they could complete their second album, David & David exploded in a haze of sex, drugs, and rock & roll; the “other” David — Ricketts — went on to behind-the-scenes work for artists like Toni Childs. Baerwald got the solo contract. A&M, seeing great potential, dumped a bunch of money into grooming him for singer/songwriter stardom. The result, Bedtime Stories, is an album that remains faithful to Baerwald’s favorite themes, yet sounds like an expensive KFOG listening party. Its merits have been debated ad nauseum by the faithful, and Baerwald himself seems to regard it with lukewarm affection. The prevailing sentiment seems to be that he “sold out” when he made this one, but I think that’s a bunch of hooey. Bedtime Stories is a more consistent album than Boomtown, contains some of his best work, and is populated, on the whole, by characters more sympathetically and subtly shaded.

Is the production slick? Sure. But it’s organic, for one thing, and for another, a lot of it was done with Larry Klein and a group of really phenomenal late-’80s Los Angeles studio players. As a result, the arrangements are engagingly complex without ever being showy. The album sags a bit in the middle, when Baerwald sacrifices memorable pop hooks for sheer stridency, but on the whole it hangs together extremely well. If it had been a big hit, there’s no telling where his career might have gone. As it happened, the absolute commercial failure of Bedtime Stories contributed to the near-total change in direction Baerwald made on his next release.

[youtube id=”xuFQ0BJrPJA” width=”600″ height=”350″] [youtube id=”XOoH3pI6_NA” width=”600″ height=”350″] [youtube id=”Nl2xZFNuGiU” width=”600″ height=”350″]

Triage (1993)

purchase this album (Amazon)

Baerwald’s never been shy about whatever his message happens to be. Triage is a harrowing album, a scathing indictment of the Reagan and Bush administrations — a shotgun blast aimed at American foreign and domestic policy of the 1980s. His statement of purpose? A picture of bloody hands held over an American flag. It isn’t exactly subtle, but then, neither is Triage. I’ve still never heard anything quite like this album. Thematically, it’s a slight reversal for Baerwald, at least insofar as that his sights are now aimed explicitly at the federal government. Where before he had contented himself with sympathetic portraits of lives bent and broken by greed — trusting the listener to make the connections — Triage is obviously political. And full of some of the blackest, most honest rage committed to tape.

His partner in crime for these sessions was Bill Bottrell, fast becoming a producer du jour for a diverse and growing stable of artists. Triage represents his most interesting work, split between songs dominated by razor-sharp hard angles (the industrial kitchen-sink approach of “The Waiter”) and those cast in unsettlingly quiet shadows (“A Bitter Tree”). For me, the culmination of this approach is the terrifying “The Postman,” which contrasts Baerwald’s gentle exhortations to have no fear against tapes of Jim Jones, congressional hearings, George Bush, and an ever-approaching military helicopter. They wrap up the album with the hopeful one-two punch of “Born For Love” and “Brand New Morning,” but really, it’s too late — it’s as though your dad kept you up all night telling you the scariest ghost stories he could think of, then looked out the window at dawn, gave you a cheerful grin, and slapped you on the back as he headed out the door. There are no safe places in Triage; the only question is whether or not to leave your nightlight plugged in. Do you want to see the slobbering, sharp-toothed beast under the bed?

The album, of course, sold next to nothing. Baerwald’s politics, increasingly dark personality, and refusal to play record-company stooge all contributed to a rift between himself and the guy running the show at A&M at the time. After Baerwald’s involvement in Sheryl Crow’s phenomenally successful Tuesday Night Music Club album, you’d think things would have been smoothed over, but no. It got personal, to the point that the label held onto Baerwald’s contract only so it could prohibit him from releasing anything while simultaneously engaging in a whisper blackball campaign against him. It would be nearly a decade before another album would surface.

[youtube id=”yM-DzyWLCV8″ width=”600″ height=”350″] [youtube id=”PDkeVwJNWww” width=”600″ height=”350″] [youtube id=”oqI4RtIQmoQ” width=”600″ height=”350″] [youtube id=”Fmi89ki9P3s” width=”600″ height=”350″]

A Fine Mess (1999)

Thank the Internet for this one. In the late 1990s, a fan named Dan put together the David Baerwald Infosource, a place for DB fans to get together, talk about his work, and hope (seemingly in vain) for new music. As it turned out, the site was discovered by Baerwald’s mother, who passed word along to the man himself, and thus began a fascinatingly open public exchange between an artist and his fans.

It also turned out that Baerwald had been sitting on not one, but two albums of new music. It was nothing he’d intended on releasing — the sessions took place largely in order to help him deal with his grief over the death of a friend’s young child — but faced with more (and more intense) interest than he’d expected, he graciously arranged for the release of the double album A Fine Mess.

It lives up to its title wonderfully. A lot of it sounds like what it was — a wake — all creaky joints and gloriously ragged edges. And hope; so much hope. Whether this is because Baerwald can see the sun again, or whether it’s simply a method of wrestling with his sadness, is impossible for the listener to say. But the effect is beautiful nonetheless. It hangs askew, like all of Baerwald’s finest work.

The production, if not completely live, at least sounds like it, and there are liberal helpings of roadhouse piano; at times, it sounds like a lost Stephen Foster album, or like Gershwin on a three-week bender. In other words, it was too good for a major label. That didn’t stop the labels from knocking, though, and it didn’t keep Baerwald from re-recording some of AFM‘s tracks in order to create Here Comes the New Folk Underground, a bowdlerized version of the album that inspired it. The best thing about Underground was that the label paid for a short tour. The worst thing is simply that it isn’t A Fine Mess. This sounds like a small complaint, except for those who really appreciate AFM for the tear-stained thing of beauty it really is.

Underground sold next to nothing, and Baerwald seems to have used its failure as a cue to turn his back on pop music, at least for now. He’s been scoring films lately (Holes, Around the Bend, and — oh yeah — there was that Grammy for “Come What May,” a song he wrote for Moulin Rouge), and his return to traditional album releases is up in the air. So download these selections from A Fine Mess — which is completely unavailable anymore, as it was released only through the website in a signed, numbered, limited edition — and enjoy!

David Baerwald – Nothing’s Gonna Bring Me Down

David Baerwald – Compassion

David Baerwald – A Prisoner’s Dream

David Baerwald – Bozo Weirdo Wacko Creep

David Baerwald – Daydreamer

David Baerwald – If Ever I Thought

David Baerwald – Love #29

David Baerwald – The Crash

David Baerwald – The Church of No Religion

Comments