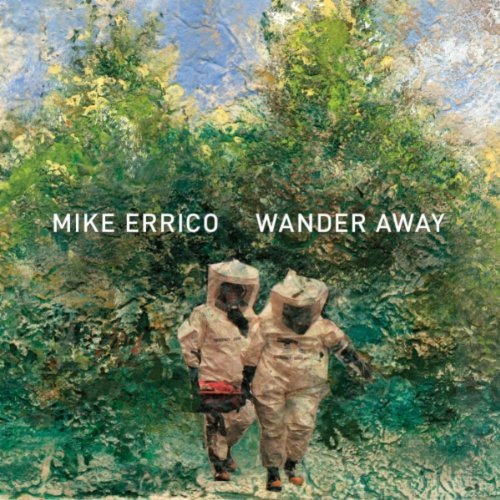

Mike Errico lost his record deal after releasing his debut album — but that was only the beginning of a journey that, over the last decade, has found his music on television (that was Mike who wrote the theme to Pop-Up Video), in films, and, of course, good old-fashioned CDs. His latest album, Wander Away, comes out next week, so we decided now would be the perfect time to talk to Mike about his career, his songwriting, and, of course, the new music.

One of the most interesting things to me about your career is that you started out at such an interesting time — you were kind of on the front lines as the industry changed.

One of the most interesting things to me about your career is that you started out at such an interesting time — you were kind of on the front lines as the industry changed.

Oh, yeah, absolutely. My first major label record came out in 1999, and that was the summer that Napster started becoming a word that people knew, and my first gig was a solo performance at Woodstock ’99, which basically burned to the ground. That was my baptism into the music industry. By fire. [Laughs]

You were on Hybrid, which was distributed through Sire, which was part of Warner Bros. — lots of cogs in a big machine. How did your deal with them collapse?

It was just sort of a thing where I felt like they, and the whole industry, were in the same boat that I was. I felt like I needed to take my songs and go elsewhere. I was very influenced by Ani DiFranco at the time, and I knew what she was doing was the right thing — and I think the label knew it, too. So we parted, and the songs I left with ended up on my next album, Skimming.

You hit the road by yourself for a couple of years after that. It reminded me of what Mike Doughty did after Soul Coughing fell apart.

Absolutely. I know Mike — he’s borrowed my guitar a couple of times onstage during bills that we’ve shared. What happened to me was that I got so lucky — a fan happened to also be a booking agent, and he’d tried forever to get in touch with me, but my management at the time didn’t pay him much attention. Finally, he got through to me, and booked me for…I don’t know how many years. Four? He was just a straight-up fan, and it happened pretty much out of the blue. I was pretty nervous about it at the time, but we became really good friends.

I wanted to talk to you about that nervousness, because you took a huge leap after you left the label — not even into the indie ranks, but totally on your own. How quickly did you start to figure out a roadmap for your career?

Not long. Let’s see, that was ’99, and I had a live record, Tonight I Drink You All, in hand by 2002 — and that would have been 2001 if not for, well, all the events that happened in New York. You know, 9/11. I recorded on September 21 of 2001. People were still scared to show up in groups. Not to overplay it, but that’s the truth, and it really changed the songs.

I was on the road with Soulive at the time, because what happened after I left the label was that all of my friends became accessible to me. [Laughs] It really shouldn’t be that way, but it opened up a lot of opportunities, and all of my best tours, and my best television appearances, my best tracks…everything opened up instantly because there was no roadmap, and all avenues became available to me. I really thought the opposite would occur, but it’s a little like the difference between driving on the highway and taking a boat through the open ocean. The ocean is scarier, I guess, but you just have to navigate by different points.

You’re pretty much on a three-year release cycle for new material, and I wanted to ask you about how that relates to your relationship with your audience. Do you feel pressure to get things out there, to maintain that connection?

I do feel a huge responsibility. What’s happened with me is that the things I give them aren’t necessarily musical — that’s always been the case to some extent; I was putting out ‘zines and other things as far back as the days of cassettes. But I also do television stuff, and things with other artists. I was an editor at Blender for awhile. That relationship with my audience is why I started my podcast, to open up that whole release schedule a lot more.

I’ve listened to it, and I think one of the cool things about you doing that is that your tale, so to speak, is fairly instructive for artists. Not just musicians, but any creative people trying to make a living with their art while navigating this wilderness. As you mentioned, you’ve done a lot of different things. Twenty or 30 years ago, someone who lost their record deal would have far fewer opportunities, but even if it’s easier in some ways to build your own career, you still have to take the initiative. You definitely did that.

Absolutely. And for me, I’ve always had interests in a lot of different areas, so if one thing wasn’t working…I’ve always had a lot of plates spinning. For better or for worse, I can’t really tell, but it keeps people guessing, and that’s something I appreciate in the artists I like. I like it when someone records, tours, shows up in the theater, does a TV theme song, or whatever.

This is an incredibly open time, with digital distribution and social networks and…whatever. I think people want to see a lot of different angles and sides. One artist I really admire is Amanda Palmer. What she’s done online — I mean, now you can find ways into her that have nothing to do with her music. Her videos. Her art. Someone could say, “Oh, I like her sketches, but I hate her songs.” [Laughter] She puts so many things out, and that’s something I’ve really connected to — that new paradigm for artists.

But at heart, do you still consider yourself a songwriter?

Yes, I do. But even early in my career, when I played live, I used to have a slideshow, and I would put the remote for the slide carousel on my microphone stand, so I could tell stories, play, and in the middle of a chord, I could click so it’d flip to a different slide. I’ve always had that other component. It’s never just been like Bob Dylan with the guitar, or just somebody very monolithic. Bruce Springsteen, you know, someone you can see doing one thing. I’ve always appreciated artists like Spalding Gray or Laurie Anderson — people whose work doesn’t fit in one set of boundaries.

So in the middle of all this, how do you strike a creative balance? How do you feed your musical craft while engaging in all this non-musical expression?

It’s super hard. That’s a super hard thing. It’s always a negotiation. Sometimes it’s saying no to a party, and sometimes it’s saying yes because the party’s going to be crazy. You know what I mean? It’s a matter of being deliberate. Jesus, do I wish I could play more — and I’m sure that’s a common complaint, but it’s really true. I was just bitching to someone that I feel like music is five percent of what I do. It kills me sometimes.

What’s your approach to the muse? Some songwriters clock in every day, and others just wait for inspiration to strike. Some are always writing, and some don’t write unless they’re working on an album.

I feel like I’m always doing something, and things will meld into one another depending on what’s needed. Like right now, I’m in the push for the new album, but as that’s going on, a couple of directors have come in because they want me to do something for a film. So then all of a sudden, my promotional brain has kicked my musical brain into gear. What I’ve been doing for weeks now — you’re talking about clocking in — is forcing myself to go to bed at 11:30, and then waking up before the alarm at 6:30, so I’m up, either pushing the record, or working on something for film or TV, or putting together the band, working on the string charts…whatever it is. It means saying no to a lot of things, and it also means definitely going out to feed your head. See a film.

Do you feel like you need a certain set of conditions to get your best songwriting done, or are you just an open channel?

Really, it’s just sleep. That’s a big one. Sleep and a strong idea — a strong focus. I need a trigger, know what I mean? I’ve been playing Radiohead’s King of Limbs nonstop lately. It’s just opened up my head, and sometimes that’s all it’ll take. Maybe a YouTube video. Like there’s this band, El Guincho. Indie pop, but very Latin — Latin rhythms, but with a lot of indie sensibilities.

For a lot of artists, it seems like a point of pride if they don’t listen to other music — “I’m too busy making my own!” — but you’ve always taken a more open approach.

Oh, absolutely. And my better half over here, just from editing her work, even that gets me going. She just gave me the Patti Smith book, Just Kids, and just the type of her writing, her compact sentence structures…they’re so terse and brilliant. I have to read that book. If I can get the goddamn time, I’ll read it, and absorb some of those rhythms.

It seems like some of your songs are autobiographical. A song like “Daylight,” for example — that story seems like it had to have happened to you. But then there’s a song like “When I Get Out of Jail” that seems more like a story. How often do you draw on your own experiences for your songs?

I’m trying to make it less…well, it’s funny. To some degree, all of these things have happened to me. But I’m trying to find the things that have happened to all of us, so I’m trying to pull my particular experience out of these things and get to a general experience, so I can say the word “I” and the listener will feel like I’m singing something about them.

And yet even a song as personal as “Daylight” contains narrative elements that almost anyone can relate to. I think sometimes, the more specific a line is, the more universal power it holds.

Absolutely. And conversely, the more universal a line is, the more wishy-washy it can get. It’s a tricky balance — I mean, that’s the art. I think Bono is someone who captures that really well, because he’s always speaking to an arena, you know? I don’t know how he asks for the salt at dinner. [Laughter] Does the entire world pass him the salt? Everything he does is so universal. I try to strike that balance.

Let’s talk about recording. How much time do you spend working on your own?

Skimming and All In were mostly done at home, but Wander Away was a lot more open. I had very definite ideas for the rhythms and melodies — which is a lot of it — but in the inside arranging, I managed to find some great minds, some great interpreters. Like Bruce Kaphan, the pedal steel player — I fell in love with his work with Mark Eitzel and the American Music Club. Oh my God. And I haven’t even met him, but we sent the tracks to his studio in California, and he’d send us back takes.

Start to finish, the songs are arranged by the time I get them out of the home studio. And I could just do the whole thing at home, but I guess I lived alone for so long that I love playing off people. [Laughs] I guess I’m sort of paying for the company. No, that’s not totally true. These are fantastic players and engineers. Of all the tools available in a studio, it’s really that human energy. It’s being able to finish a take and say, “Was that good? Did that suck?” Getting good minds into a room makes something better.

I know you said you wanted to work more with atmosphere on this album, and going back and listening to your releases in sequence, it struck me that each of them sounds bigger — and bigger-budget — than the one you put out through a major label.

I know you said you wanted to work more with atmosphere on this album, and going back and listening to your releases in sequence, it struck me that each of them sounds bigger — and bigger-budget — than the one you put out through a major label.

[Laughs] Yeah, and I think if you added up all of the budgets for those albums, they’d come out to less than half of my debut.

Independent musicians have more tools, and more affordable tools, at their disposal now. Pictures of the Big Vacation was really strongly rooted in acoustic guitar.

If I told you, I don’t know if you’d laugh or keel over at how expensive that first album was. It was ridiculous. If the later albums sound bigger, I feel like a lot of it is because I know the studio more, and the songs continue to grow. This was the first album where I used strings, for instance. Such gorgeous moments in those sessions — I have some great memories of those.

How often do you approach an album with a pre-existing framework established? Knowing, for instance, what kind of sound you’re going after?

I definitely went into Wander Away with that framework.

And did you write the songs to fit it, or did you have them already written?

I had most of them, and the whole creative process was sort of moving in one direction. I was writing a lot for television at the time, and working in the studio where I ended up recording the album, and it’s a very warm place. I’d always wanted to get that warmth, that sound, and all of a sudden, I knew this was the place.

It’s interesting that you say “warmth,” because I think this is your warmest record, and it has an intimacy that even an acoustic song like “When She Walks By,” from your first album, doesn’t have.

Yeah, I even changed the way I sing. I wanted to relax. To chill and feel what’s right. That’s where Ken Rich, who produced with me and mixed the album, really came into play. My neurotic perfectionism would come up, and he’d say, “No no no no no, don’t touch it.” What I might hear as a mistake, he identified as the best thing about a take. I did trust him, and I was just kind of white-knuckling it for awhile there, but the result is a much warmer piece of work. I wasn’t trying to make any hard turns and make everyone fly out the window — that wasn’t the idea. The idea was just to keep going and get something new. I think it worked.

Related articles

- The Popdose Interview: Joe Washbourne of Toploader (popdose.com)

- The Popdose Interview: Michael Gomoll of Joey’s Song (popdose.com)

- The Popdose Interview: Alex Dezen of The Damnwells (popdose.com)

- The Popdose Interview: Lee Feldman (popdose.com)

- The Popdose Interview: Tom Johnston of The Doobie Brothers (popdose.com)

Comments