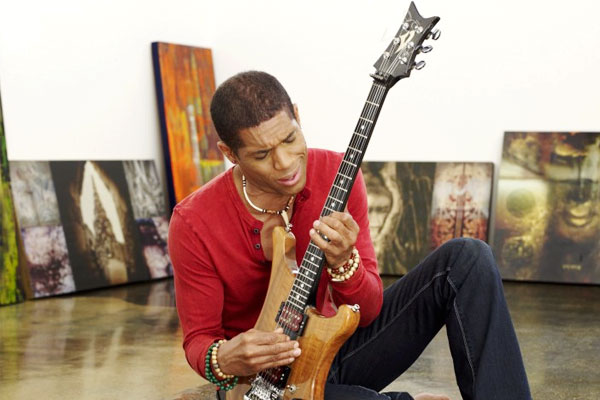

He’s never exactly been a household name, but Stanley Jordan has always commanded a certain amount of attention and respect in the jazz community, particularly among guitarists. To understand why, all you need to do is spend a few minutes watching him play; his use of the eight-fingered tapping style he calls the touch technique is not only visually spellbinding, it’s enabled him to do some fairly amazing things, including playing two guitars at once (as he did on his 1994 album, Bolero) and playing guitar and piano simultaneously.

But Jordan’s music isn’t all flash — in fact, quite often, his exceptional dexterity doesn’t even translate to the songs, which have always been crafted around emotion, sometimes to the frustration of fans who just want him to put on a show. He’s always stayed resolutely true to his muse, even when it meant taking a nine-year break from recording — and then returning in the early aughts with a pair of esoteric albums inspired by his studies in music therapy.

Over the last few years, Jordan has edged back toward the broader jazz marketplace, and his most recent release, Friends, offers perhaps his broadest commercial overture since Bolero. On it, he’s joined by a stellar cast of guests, including Charlie Hunter, Mike Stern, and Kenny Garrett; together, Jordan and his Friends run through an inspired set of originals, covers (including, yes, Katy Perry’s “I Kissed a Girl”), and a nod to one of his classical favorites, BÁ©la BartÁ³k.

I’ve loved Stanley Jordan’s music since stumbling across his cameo in Blake Edwards’ Blind Date almost 25 years ago, so getting to talk to him about Friends was a real personal thrill, and in conversation, he was just as thoughtful and honest as his playing. Read on.

Your technique has obviously gotten a lot of attention — more, I’d argue, than most artists, even in the jazz sphere. Do you ever feel like that’s put an undue burden on expectations for your music? There’s always this tension between melody and chops in jazz, and someone in your position is always in danger of being accused of straying too far on either side of the line.

I think there are general issues in the aesthetics of music that were always there before me. I kind of stepped into that world, and I’d like to see musical aesthetics evolve — I’d like to see people taking it a little more seriously. A lot of people, rather than thinking their opinions through clearly, will just express judgments that reflect their aesthetic beliefs, and an assumption that that’s the way things should be. When someone comes along and does something that’s difficult to categorize, the reactions can be all over the map.

In my case, I’ve had people who say “he’s all chops, he’s just showing off his technique,” and then other people who complain because they hear a lot of melody, and they don’t think I’m doing enough heavy, deep stuff. So what am I? Am I overdoing it, am I underdoing it?

I also like a lot of different types of music. I don’t think I’m all that unusual in that regard, but I’ve always had that attitude. When I was getting around New York in the beginning of my career, in the late ’70s and early ’80s, I met musicians who gave me career advice, and one of the things I heard a lot was “You have to pick a style. It doesn’t work like that. You can’t play all these different things.” I think they were right, at least to the extent that it has been kind of difficult to carve out a niche. But I feel like it’s been worth it, because at the end of the day, we have to be true to ourselves.

It’s funny in jazz. I stopped going to a lot of these jam sessions. It’s a shame, but I often felt like it was just one big cutting contest, and if I’m playing with someone, I like everyone to sound good together. That was one of the goals with the Friends album — obviously, there’s a sense of competition in that we’re all pushing each other, but there was so much love in the studio, and I really went out of my way to make people feel comfortable, and sit back and let them shine. The album was really more about them than it was about me.

And I did worry a little that people might think I should step up more. But really, when I’m playing with the touch technique, I don’t even think about that. I’ve been playing that way for so long that I forget. I can go two, three, four shows in a row, and the whole time it doesn’t occur to me that I have an unusual technique, because that’s just me playing the guitar.

Stanley Jordan – Friends – EPK from Mack Avenue on Vimeo.

Right, and I think that comes across watching you play. Even when you’re doing something amazing, like playing guitar and piano simultaneously, that isn’t necessarily reflected in the music itself. There’s nothing in the song that sounds like you’re winking at the audience.

Well, even that, I mean…okay, I’ve been doing it more seriously in the last few years. But even in the beginning, when I started working with the touch technique, it occurred to me that I could play guitar and piano. One of the reasons I shied away from it was that I didn’t want people to think it was a gimmicky thing, but after awhile, I started to feel like I was cheating myself. It was something musically that I really wanted to do. When I play guitar and piano together, it’s like one instrument, but it’s one instrument with a broader range of colors. I love the musical possibilities in that.

When you normally hear guitar and piano together, there’s obviously more that two players can do than I can when it’s just me, but they…blend into one. People have asked me if doing that turns my trio into a quartet. [Laughter] The answer is that it’s definitely a trio. That’s how I want it to come across — one person playing one instrument with some unique, amazing possibilities.

When I picked up my copy of Friends for the first time, I was thrilled to see that you played with Mike Stern and Charlie Hunter on the album. You make a sort of G3 for hardcore guitar geeks — you know, guys who have a lot of respect in the field, but haven’t achieved Metheny-size sales success.

Right, but it’s amazing how many people love their music. And I’m glad you mentioned that, because — maybe more in Mike’s case — they’re great guitarists that guitar players know and love, and they need to be heard more. And also Kenwood Dennard on drums — again, drummers know he’s amazing. I’ve been playing with him for years, and inside the musicians’ community, everyone loves him, but more people need to hear him, so I wanted him to be the only drummer on the album. And then there’s Russell Malone and Bucky Pizzarelli — those guys could make up part of another G3.

We might actually do some shows in that format, although it’s hard to get everyone together. I’d love to do a Friends reunion where we all play live together, but I don’t think it’s possible.

From the outside, you seem like a guy who was supposed to really grab that brass ring in terms of sales — you even got Arista to enter the jazz market — but then you walked away from all that and started making really deeply personal music. So a project like Friends, that includes some big names and includes, you know, a Katy Perry cover, might seem like a commercial concession. I’m guessing that wasn’t the motivation at all.

These are among my favorite artists. The fact that they have a high profile does help sales of the album, and I think it’s good to make a record that sells. You know, we were talking about aesthetics, and that’s one of the areas where the jazz community shoots itself in the foot — we have this bias against success, and then we sit around and wonder why the world isn’t beating a path to our door. There’s some bitterness against players who have achieved success in the rock world with music that doesn’t have the depth of some jazz.

And yet they’ve been able to be so successful marketing themselves. If we took a page from that book, we’d do so much better. We want people to like jazz, but we aren’t willing to do what it takes to get the word out. I don’t agree with that approach. So yeah, I expected that high-profile artists would help the record do well. But really, they were chosen primarily for their skills, and their musicianship, and how much I love them as artists. The music comes first. The music always comes first.

The Katy Perry song…well, first of all, jazz artists have always covered pop songs, so I’m not doing anything different there. But the thing that really got me excited about doing “I Kissed a Girl” in particular was watching her do an MTV Unplugged version. She obviously had jazz musicians playing with her, and the way she dressed, and the way she set it up, it was kind of this smoky jazz cafe sort of atmosphere. I liked the concept she was going for, and the image she was portraying, but she didn’t give those cats any solos! So I thought it’d be cool to do an actual jazz version, but I was really just continuing what Katy Perry started.

When I’m putting styles together like that, I want to do it organically. I don’t want to just throw things together out of the blue if they don’t make sense. To give you another example, there’s something that Mozart did in a lot of his pieces — a resolution where he’d take the augmented second and resolve it up to a major third. To me, when I hear that, it sounds like the blues — that’s what that is, basically. So when I played a movement from one of his piano concertos on my State of Nature album, I took it and made a blues lick out of it. I feel like it works because Mozart already gave me permission himself, you know? And history says he improvised a lot on that particular composition, so I did it too.

So here with “I Kissed a Girl,” the composer is Katy Perry, and she said the song could be done in a jazz way, so I said “okay,” and took it the rest of the way.

[youtube id=”wpf9UWtvJmc” width=”600″ height=”350″]It’s refreshing to hear your take on the jazz “sellout” debate. I think a lot of artists struggle with that.

You know, what I really love about popular music is its raw power. Its energy. If you can marry that to the more sophisticated structures you get on the jazz and classical side, I think you’ll find the amazing new integral music of the future. I love that word, integral, and I’m a fan of Ken Wilber’s philosophy. I think it applies to music as well.

He talks about the difference between integration and fusion, and you see it in music, too. Fusion is where you kind of melt things together and end up with something that’s a little this and a little of that — neither here nor there. With integration, you’re putting things together and creating something new, but the original elements are still really there. I like my rock to be rock, and my jazz to be jazz. When I put them together, I like it to be jazz rock. You know?

I remember before fusion was a thing, they called it jazz rock. Then it was rock fusion, and then it kind of started to become more bland.

And then fusion became a four-letter word.

Right, right. Whereas for me, I’ll do things like…for example, I covered Michael Jackson’s “The Lady in My Life,” and I’d describe my approach to that performance as jazz soul. I didn’t have the word “fusion” in my head, but I liked taking the R&B and soul elements and mixing them with jazz. That means there are things you wouldn’t do, because they wouldn’t really work — so in other words, everything has some constraints on it.

Everything has some sort of limit. Artistically, it’s about working within those limits. But on “Lady in My Life,” for instance, I think I did some things on my solo with some of the intervals and patterns I played that nobody was doing. It’s interesting to me that some people will hear the beat to a song and classify it without hearing the music. They’ll say they don’t like it, but they don’t notice that there are some innovative lines going on in there.

Back when I was first getting my concepts together, I was really influenced by a book called Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. It contains some really good points that can be applied to music. For instance, the author points out that a lot of people lose the ability to draw as they get older, because every picture they want to create is already attached to a concept. They could be looking right at you and try to draw your nose, but they aren’t really drawing what they see, they’re drawing “a nose.” It always ends up looking the same, and it isn’t good art.

So the author suggests turning it upside down, so it’s no longer a mirror of your preconceived image. It’s a light area, and a dark area, and so on. You draw the lines and the shapes and the flow of the energy, and boom — you end up with a drawing that really jumps off the page. I think it’s the same thing with music, where listeners — and musicians, too — will go in with a concept, and it’s no longer based on sound, tone, energy, structure, or any of the fundamental energies of music.

[youtube id=”G3gHtPLXQOI” width=”600″ height=”350″]You’re talking a lot about energy, but it seems like one of the crucial differences between fusion and integration would be a firm grasp of theory.

I think that really helps. I’m a theory buff from way back; I have a degree in theory and composition, and there’s still so much. It’s infinite. I do feel that it’s helped me, because it gets me out of the box sometimes. I’m always aware. I’m often reminded of a good friend of mine from college, who was a mathematician, and we’d talk a lot about his work, which had to do with algebraic topology. He was studying manifolds in 14 dimensions and so forth.

One day I asked him, “Bill, don’t things get really complicated after the fourth or fifth dimension?” and he said, “Actually, things simplify. With more dimensions, you have more space — it’s easier to do things because you have more places to put stuff.” It’s just like cleaning your room — if you have a big room, you can move stuff over here for awhile so you can concentrate on this other section.

I think it’s the same thing with theory. The more you know, the more room you have to work, because there’s always something else you can bring in to make the piece fit together.

But is there ever a tension between all that theory and the energy you’re talking about?

There can be, yes. And this is one of the things I talk to my students about. The mind and the heart and the hand — there can be tension between any two of those things. I tell my students to try and remember that they’re holistic people, and to try and integrate all those things. It can be useful to focus on one for a period of time, and section it off, but you have to reintegrate it later.

If you’re working on theory, let’s say you’re learning 10 new scales. Well, realistically, you probably don’t have enough time to play all of them in a musical way, so I’d suggest picking three and using your knowledge of theory to choose the ones that represent all 10. Start with the first one, and really, really stay with that scale until you feel like you’re making music with it. Until you know it like a friend.

That takes time — it has to settle in. You can’t predict; you have to sit with it. I often tell my students that they have to slow down, because the mind is faster than the heart. You have to give the heart enough time to catch up — but you need the heart, because the heart gives guidance to the mind. The mind knows of a jillion possibilities, but the heart knows which one is the best one right here and now.

[youtube id=”lQZY87PDsnQ” width=”600″ height=”350″]We’re kind of skirting around the edges of music therapy, which is a field you’ve explored pretty deeply over the last decade or so. I’d like to talk about that now, and about how music therapy influenced your work on Friends.

Music therapy wasn’t so much of a conscious thought when I was making Friends. I think it was more in the forefront of my mind when I was making my last album, State of Nature. With that album, I was trying to do global music healing, in a sense, by using music to try and help people feel their connection with nature more — and to be more thoughtful about it, too.

When it came to Friends, even though I didn’t have that thought in my mind, music therapy ended up being part of the album anyway, because I’ve always been kind of an introvert. A lot of people don’t know that about me, because they only see me when I’m confident — I only emerge when I’m ready to deal with people, and then I disappear for awhile. A lot of times, I feel socially awkward, because when I was younger, I spent so much time practicing that it was almost sort of a substitute. I didn’t have the nerve to go talk to that girl, but then she’d see me perform, and then maybe she’d be more receptive.

So I kind of developed in a weird sort of way, and what Friends did was help me come out of my shell and be more social. On this album, I’m the host. I’m the one going around to everybody and making sure they’re comfortable, and they have everything they need. That helped me feel comfortable.

I think there’s really a connection. I developed my whole style of playing solo because I loved people like Joe Pass, but there was another element to it; sometimes I had difficulty finding people who wanted to play when I wanted to play, or who wanted to do things I wanted to do. Sometimes you get into a band situation and there’s all this other noise that goes on, and I was just…forget it. It was easier to play solo. My social deficiencies may have been why I developed so much of a solo style in the first place. So this time around, I decided to pursue the musical opposite — I think this is the first album I’ve done where there isn’t a single solo song on it. It really was healing for me in that way.

Do you feel like you’ve mastered your craft at all? To what extent do you still feel like a student?

I’m always going to feel like a student. The more you know, the more you know you don’t know. That’s what my teacher Elroy Jones always told me, and he was right. I’m always going to hear all the things that didn’t quite work out — to hope I managed to play those things off. There’s always going to be that kind of insecurity, I think.

But sometimes I sit back and think about all the ground I’ve covered so far, and I do feel proud of that. I see young guitarists coming up, and they don’t worry about playing in an unusual way, because they don’t have anything to prove. It’s a little like the younger gay or TG generation — for them, it’s just an alternative lifestyle, and it doesn’t bring with it the same type of struggle it did before. I do feel like I’ve made a difference with my instrument that has made it okay to play differently, or to do the kinds of things I’m doing.

One of the things I’m really excited about is work I’m doing with my harmonic vocabulary. It’s been a long-term project — it’s really been decades now — but lately I’ve been putting more energy into it, and I feel like it’s coming to fruition in a new way. I have kind of a big harmonic vocabulary, but it doesn’t always occur to me when I’m on the spot. On stage, I tend to fall back on the things that are comfortable, but once in awhile I’ll remember what I know, and I love those moments of creation.

Lately, I’ve been training myself to use more of what I know. It’s a balance, because I don’t want to overdo it and play something that doesn’t make sense musically. But basically, I’m working off a list of about 1300 chord types — and what I mean by chord types is chords and scales. They’re the same, so I call them both chord types. So there’s 1300 of them, and they can be played in all 12 keys, so it’s a pretty big list, and I’ve been really getting deeply into it. Just loving the exploration of it. I want five or six more lifetimes, and there’s no way I can even make a dent in it.

So what I’m really excited about is teaching. I want to develop a method so that people can learn this quickly — these different approaches to voicing on the guitar. I’ve come up with a way of modeling and notating it; I’m still kind of working on the terminology a little bit, but the concept is totally in place. I’ve discovered what is kind of a unified field theory of chord structure, and I’m really excited to develop and teach it. I’m going to be putting an educational website together. Of course, my technique stuff will be there, but the theory and composition side is what I’m the most excited about. That’ll explain this unified harmonic theory.

We’ll also get into aesthetics, which we haven’t really had time to talk about today. I think you can use ideas from aesthetic philosophy to help invigorate our discussions in the field of music criticism, where I feel we’ve hit an impasse, and there’s a bit of a battle between the artist and the critic. I think we can heal that by clarifying what musical criticism is, and the principles we come from. There are times when we should agree to disagree, but we’re just disagreeing to be disagreeable. I think we can heal some of that if we can find a common language, and I feel aesthetic philosophy provides for that. I’d like to get other people involved in that, and build a community around it.

Comments