One night not long ago, our little hamlet in central Pennsylvania fell under a vicious, unprovoked attack by a line of thunderstorms sufficiently severe as to knock out power on my block for an entire evening. I heard the lightning strike that did it—it was a mighty thing, possibly hurled by Zeus (that showoff) himself. I heard the pop of a nearby transformer and knew that, in spite of Met-Ed’s hopeful operator’s predictions, we would be without tha juice at least until morning.

One night not long ago, our little hamlet in central Pennsylvania fell under a vicious, unprovoked attack by a line of thunderstorms sufficiently severe as to knock out power on my block for an entire evening. I heard the lightning strike that did it—it was a mighty thing, possibly hurled by Zeus (that showoff) himself. I heard the pop of a nearby transformer and knew that, in spite of Met-Ed’s hopeful operator’s predictions, we would be without tha juice at least until morning.

Not a problem for the wife, the kid, or the cat (who lounges and snores like he owns the place, which, of course, he does). Big problem for Big Papa here, as I suffer desperately from sleep apnea and require the assistance of a forced-air machine to keep from ceasing breathing 120 times an hour (I wish I wuz kidding, folks; one doc suggested a tracheostomy to relieve the issue. I demurred politely and got the fuck out of his office as quickly as I could). Said machine requires power and, without any to feed it, I sat up in bed—uncomfortably, for beds are for reclinin’ in—and occupied my mind the way I typically do in such situations, by recounting the various women to whom I have been attracted and with whom I have not slept. The lust list begins with Kristy McNichol in 1975 (I had a smutty mind when I was in kindergarten), continues through 1979 (Jill Whelan), breezes through the mid-Eighties (ah, Amy Steel, where are you now?), and achieves an extended, sad crescendo in college. In fact, there are so many from the college years, I often get trÁ©s bummed out, and abandon the list before it is completed.

My internal soundtrack for this pathetic reverie was Bob Dylan’s “Tight Connection to My Heart (Has Anybody Seen My Love),” not for any thematic or aesthetic reasons, but because I had spent some time earlier in the evening, before the storm, reading the five or so pages Clinton Heylin devotes in his fine Dylanography Behind the Shades Revisited, to the making of 1985’s Empire Burlesque, the album from which “Tight Connection” hails. Empire had been on my mind in recent weeks, as I struggled with coming up with a record to discuss in this column that didn’t involve listening to Dan Fogelberg.

My internal soundtrack for this pathetic reverie was Bob Dylan’s “Tight Connection to My Heart (Has Anybody Seen My Love),” not for any thematic or aesthetic reasons, but because I had spent some time earlier in the evening, before the storm, reading the five or so pages Clinton Heylin devotes in his fine Dylanography Behind the Shades Revisited, to the making of 1985’s Empire Burlesque, the album from which “Tight Connection” hails. Empire had been on my mind in recent weeks, as I struggled with coming up with a record to discuss in this column that didn’t involve listening to Dan Fogelberg.

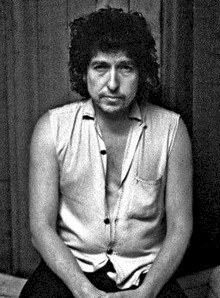

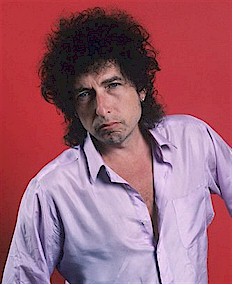

In fact, I had written and discarded several hundred words elucidating my theory that the Bob Dylan who recorded from 1967 to 1990 was not the true, authentic Bob Dylan, but a Bob Dylan who wore a mask bearing the visage of yet another “Bob Dylan,” one who, instead of following a line of art true to his own interests and muse, spent the better part of a quarter century simply giving his fawning but shrinking public what he thought they wanted. James Taylor and the aforementioned Fogie were big, so he put out New Morning, Blood on the Tracks, and the like. There were people who never got to hear him play with the Band and wanted to experience that privilege, so we had Planet Waves and Before the Flood to enjoy. Elvis had made a go of it in Vegas before dying on the toilet, so Dylan went to Japan and did his very best audition for the International Hilton (toilet and all) on Bob Dylan at Budokan. He fell under the spell of Christian fundamentalism, so he made the pastor-pleasing Slow Train Coming and Saved (and, to a lesser extent, Shot of Love). Later, with Peter Gabriel’s So and U2’s The Joshua Tree riding high on the charts and public consciousness, Dylan opened the door and in trotted Daniel Lanois, carrying a gris-gris bag and an echo pedal, smelling of patchouli and Creole seasoning (albeit of a Canadian origin). Together, they made Oh Mercy, one of his most popular “return to form” albums of the Eighties.

My theory holds that not until 1992’s Good as I Been to You and, especially, 1993’s World Gone Wrong (a major Bob Dylan record, regardless of whether anyone knows it, though I have it on good authority that Dylan himself did), did the true Bob Dylan reemerge, croaking old railroad songs and sea shanties, and absconding with their imagery, melodies, and snippets of their lyrics for every studio record he’s made since. The real Bob Dylan plays on, even today—the septuagenarian Grandpa Bob, jokester, bandleader, piano player—touring summer sheds and delighting audiences with unrecognizable versions of tunes they all—we all—know by heart. He’s a natural extension of the twentysomething kid who set all kinds of shit on fire, gave rock musicians a new language to learn, and made the world safe for the likes of Donovan and Paul Simon, Gawdblessum, before crashing his motorcycle in 1966 and taking himself out of the game.

My theory holds that not until 1992’s Good as I Been to You and, especially, 1993’s World Gone Wrong (a major Bob Dylan record, regardless of whether anyone knows it, though I have it on good authority that Dylan himself did), did the true Bob Dylan reemerge, croaking old railroad songs and sea shanties, and absconding with their imagery, melodies, and snippets of their lyrics for every studio record he’s made since. The real Bob Dylan plays on, even today—the septuagenarian Grandpa Bob, jokester, bandleader, piano player—touring summer sheds and delighting audiences with unrecognizable versions of tunes they all—we all—know by heart. He’s a natural extension of the twentysomething kid who set all kinds of shit on fire, gave rock musicians a new language to learn, and made the world safe for the likes of Donovan and Paul Simon, Gawdblessum, before crashing his motorcycle in 1966 and taking himself out of the game.

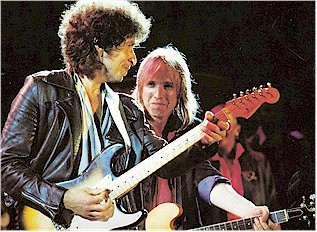

Toward the end of the inauthentic period, between the Christian records and Oh Mercy, the “Bob Dylan” who roamed stages sporting teased hair and dangling earrings and hung out with Tom Petty made several albums that were interesting in large part because they balanced his typical urge of the time to please people, with a counterbalancing tendency to not give a shit. This period gave us the warm, Mark Knopfler-produced Infidels, shortly before Knopfler went supernova with Dire Straits’ Brothers in Arms. It gave us Empire Burlesque, on which “Dylan” began a long stretch of producing himself, with the assistance of outside help brought in to help make his records sound more “modern.” For Empire, it was Arthur Baker, remixer extraordinaire, who layered in synths and background vocals. Subsequent records would see people like Petty, Paul Simonon, Eric Clapton, Ron Wood, Robert Hunter, the Grateful Dead, and others involved, sliding in and punching songs up or out. It didn’t seem to matter to this “Dylan” who was involved. He needed something to tour behind, and these records fit the bill.

[This is not to say there weren’t some really good songs to come out of this period—any Dylan period that included moments like “I and I” (from Infidels), “Brownsville Girl,” “Got My Mind Made Up” (both from Knocked Out Loaded), and a chilling cover of Hank Snow’s “Ninety Miles an Hour (Down a Dead-End Street)” (from Down in the Groove) cannot be completely discounted, and that doesn’t even count the quality songs that got left off the records, like the transcendent “Blind Willie McTell,” inexplicably dropped from Infidels. There was a lot “Dylan” did during this period that defied explanation.]

[This is not to say there weren’t some really good songs to come out of this period—any Dylan period that included moments like “I and I” (from Infidels), “Brownsville Girl,” “Got My Mind Made Up” (both from Knocked Out Loaded), and a chilling cover of Hank Snow’s “Ninety Miles an Hour (Down a Dead-End Street)” (from Down in the Groove) cannot be completely discounted, and that doesn’t even count the quality songs that got left off the records, like the transcendent “Blind Willie McTell,” inexplicably dropped from Infidels. There was a lot “Dylan” did during this period that defied explanation.]

Back to my dark, electricity-free night of the soul. As my roll call of sexual frustration petered out, I groggily began to contemplate the snippets of “Tight Connection to My Heart” that resonated most with me. The randomness of the imagery in the song somehow, cumulatively, makes sense. It’s a relationship gone sour, lost to the vagaries of one’s wanderlust, or one’s illicit occupation (or preoccupation). The first verse sounds like something Miami Vice‘s Sonny Crockett would have told a woman who’d fallen in love with him, several days after he’d left her, alone, in a different bed:

Well, I had to move fast

And I couldn’t with you around my neck

I said I’d send for you and I did

What did you expect?

My hands are sweating

And we haven’t even started yet …

I’m gonna get my coat

I feel the breath of a storm

There’s something I’ve got to do tonight

You go inside and stay warm

Dylan goes on with more fluid imagery. “Madame Butterfly” lulls him to sleep “in a town without pity / Where the water runs deep.” It’s almost as if he were flipping through a TV Guide or a magazine, copying down arbitrary phrases, until he had enough to weave together. Later in the song, he tells of a crowd “beating the devil out of a guy wearing a powder blue wig,” how he can still hear the man’s “voice crying in the wilderness.” Then he hits home with my favorite lines in the song:

Never could learn to drink that blood

And call it wine

Never could learn to hold you, love

And call you mine

It fairly snaps the head back, that little uppercut of a verse. Clinton Heylin takes issue with it—an earlier version of the song (later released on the first Bootleg Series box set) made references to Babylon and, further imbuing the verse with religious overtones, replaced the last two lines with “Never could learn to look at your face and call it mine.” One might argue, as Heylin does, that one’s inability to see God’s face, or Christ’s face, and the inability of that person to partake of the Eucharistic blood, made the song deeper and more resonant. However, I counter that anyone who’s endured a difficult relationship’s dissolution will recognize the unwillingness to drink anything offered by the soon-to-be ex—blood, wine, Kool Aid, whatever—and accept it for what the other party says it is.

It fairly snaps the head back, that little uppercut of a verse. Clinton Heylin takes issue with it—an earlier version of the song (later released on the first Bootleg Series box set) made references to Babylon and, further imbuing the verse with religious overtones, replaced the last two lines with “Never could learn to look at your face and call it mine.” One might argue, as Heylin does, that one’s inability to see God’s face, or Christ’s face, and the inability of that person to partake of the Eucharistic blood, made the song deeper and more resonant. However, I counter that anyone who’s endured a difficult relationship’s dissolution will recognize the unwillingness to drink anything offered by the soon-to-be ex—blood, wine, Kool Aid, whatever—and accept it for what the other party says it is.

And I never got to sleep with Kristy McNichol.

Empire Burlesque gets a lot of critical shit for its Á¼ber-Eighties sound, its thin, synthy textures, and Dylan’s thinner, reedy croak. It does, however, have its share of warm moments. The trio of romantic songs on the record—“I’ll Remember You,” “Never Gonna Be the Same,” and “Emotionally Yours”—are more successful in their execution of intended sweetness than most of the rest of the record’s songs were at furthering the Dylan mythology, or bringing it into a modern context. “I’ll Remember You,” in particular, is a subtle yet resounding trifle, a fond, seemingly simple farewell to a woman the singer has been with only briefly, and his regret over their relationship’s brevity seeps from each verse. “I had so much left to do,” Dylan sings, “I had so little time to fail.” He knows she’ll be on his mind for a good long time—”When I’m all alone in the great unknown,” “When the roses fade and I’m in the shade,” “When the wind blows through the piney wood”—and each instance of memory will strike him, and strike him hard. Ultimately, he knows he must let her go:

Though I’d never say

That I done it the way

That you’d have liked me to

In the end

My dear sweet friend

I’ll remember you

Elsewhere, the inauthentic “Dylan” dons the mask of the truth-teller, giving him ample opportunity to point his finger and yell, “Shame!” “Clean Cut Kid” decries the conscription of a young man with no business going to war:

Elsewhere, the inauthentic “Dylan” dons the mask of the truth-teller, giving him ample opportunity to point his finger and yell, “Shame!” “Clean Cut Kid” decries the conscription of a young man with no business going to war:

They said, ”Listen boy, you’re just a pup”

They sent him to a napalm health spa to shape up

They gave him dope to smoke, drinks and pills

A jeep to drive, blood to spill

They said ”Congratulations, you got what it takes”

They sent him back into the rat race without any brakes

He was a clean-cut kid

But they made a killer out of him

That’s what they did

Dylan practically spits the words out; he sounds more alive, more in the moment, than at any other point on the album. The version of “When the Night Comes Falling from the Sky” that made it onto Empire Burlesque sounds just the opposite. It’s another desperado’s tale, its lyrics full to bursting with a mixture of recrimination and desolation, but Dylan’s vocal and accompaniment squander the power of those words. Over a bed of ridiculously layered keyboard tracks and synth drums, Dylan’s zombie wheeze veers into self-parody, drives through self-parody, skids to a stop, then backs up through self-parody again. And repeats the process. It’s appalling, and a shame, because a discarded version of the song—with different melody, and E Streeters Roy Bittan and Steven Van Zandt playing real instruments—later turned up on the first Bootleg Series box, sounding so alive, with Dylan so engaged in the rich layers of lyric. The outtake would have easily been the highlight of Empire Burlesque, but alas, without a synthesized horn section and Linn drum, it had no place on the record.

Dylan practically spits the words out; he sounds more alive, more in the moment, than at any other point on the album. The version of “When the Night Comes Falling from the Sky” that made it onto Empire Burlesque sounds just the opposite. It’s another desperado’s tale, its lyrics full to bursting with a mixture of recrimination and desolation, but Dylan’s vocal and accompaniment squander the power of those words. Over a bed of ridiculously layered keyboard tracks and synth drums, Dylan’s zombie wheeze veers into self-parody, drives through self-parody, skids to a stop, then backs up through self-parody again. And repeats the process. It’s appalling, and a shame, because a discarded version of the song—with different melody, and E Streeters Roy Bittan and Steven Van Zandt playing real instruments—later turned up on the first Bootleg Series box, sounding so alive, with Dylan so engaged in the rich layers of lyric. The outtake would have easily been the highlight of Empire Burlesque, but alas, without a synthesized horn section and Linn drum, it had no place on the record.

Empire closes with its most uncharacteristic track, “Dark Eyes.” Accompanied by just his acoustic guitar and harmonica, Dylan again strings together a series of seemingly unrelated images that, in combination, form scenes of emotional upheaval and regret. According to legend, Dylan wrote the song after passing a call girl in the hall of his hotel, she having just left the room of a client. Perhaps it is her voice he is speaking through in the song’s penultimate verse:

They tell me to be discreet for all intended purposes,

They tell me revenge is sweet and from where they stand, I’m sure it is

But I feel nothing for their game where beauty goes unrecognized,

All I feel is heat and flame and all I see are dark eyes

It’s a fine song, though one Dylan has only performed live eight times in 27 years; indeed, he’s treated it like the throwaway tune it probably was.

Many consider Empire Burlesque to be a throwaway record; it’s a perspective I understand, but disagree with. I prefer to think of the album as emblematic of a difficult period for Dylan—one in which he struggled both to please people and to distance himself from his authentic muse. He pretty much failed on the first count—Empire sold as poorly as most of his albums of the period. How much he succeeded at the latter has only become more apparent with time, and with the quality of his recorded output in the last 20 years.

Ultimately, though, there are enough moments on the album to make it worthy of returning to, particularly on dark, stormy nights.

Comments