I have recently rekindled my love affair with vinyl records. It’s been a while; I haven’t had a working turntable in some time, plus, I wanted to carve out a space to enjoy records in the shithole that is my home office. Getting a turntable was easy; cleaning my office took months, and is a story for another column (or an episode of Hoarders dedicated to magazine addicts).

I have recently rekindled my love affair with vinyl records. It’s been a while; I haven’t had a working turntable in some time, plus, I wanted to carve out a space to enjoy records in the shithole that is my home office. Getting a turntable was easy; cleaning my office took months, and is a story for another column (or an episode of Hoarders dedicated to magazine addicts).

I admit that vinyl collecting is not an original hobby—I know quite a few people who do it, several of whom work for or around this very site and have written quite extensively and beautifully about the music and the medium (see Shane, Ken, “Cratedigger”). I have gone back in large part because I missed the rituals of finding and listening to music, as opposed to simply accumulating it.

Don’t get me wrong; there is nothing—absolutely nothing—bad about being able to listen to damn near anything I want with just a couple mouse clicks. However, it gives me great joy to actually shop for music again, at thrift shops and swap meets and one particular honest-to-God record store about 40 minutes from my house. I love bringing my purchases home, handling them carefully, cleaning them, taking care of them. Enjoying the artwork. Reading the liner notes and lyric sheets. I like the sound of records, from the little “donk” when the needle finds the groove, through to the “thwap” it makes when it hits the run-out groove (I’m not crazy about static, though, and I hate skips, but I roll with what I hafta roll with).

And so, I place my “Death by Power Ballad” column on temporary hiatus, and begin here writing of the sounds, both old and new, I am experiencing as a result of my reunion with real, trax-on-wax-style records. The music will always be the main story, but there will also be some digressions into the personal, or a snippet of something historical, or sometimes just a riff in words meant to complement or extend the riffs in the grooves. I also intend to re-evaluate the work of some artists I might have not quite understood at first, as well as some I have spent the past 30 or more years detesting (DanFans and Fogelfarts, take note).

So where to begin such an undertaking? I begin with disco, or, more to the point, with a particular non-disco act that attempted to go disco. But really, I begin in New Jersey, in the bedroom of my two cousins (the older brothers I never had), sitting in front of their multi-component stereo system, marveling at the dozens upon dozens of records they had, noting the care they took to keep those records looking and sounding great; noting, also, the wonderful tremendousness of volume at which they tended to play those records.

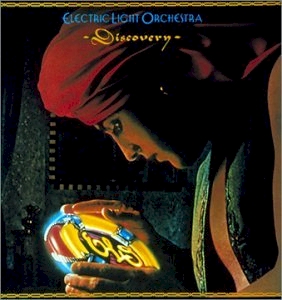

One was E.L.O.’s Discovery. I knew nothing about the band, except the singles that I loved that were all over the radio—”Last Train to London,” “Don’t Bring Me Down,” “Shine a Little Love”—and that was enough. I didn’t know about the band’s past pomp-pop excursions, its leader’s Beatles fixation, or the fact that this foray into dancy fare (keyboardist Richard Tandy referred to the album as Disco? Very!) was at all a digression from past glories.

One was E.L.O.’s Discovery. I knew nothing about the band, except the singles that I loved that were all over the radio—”Last Train to London,” “Don’t Bring Me Down,” “Shine a Little Love”—and that was enough. I didn’t know about the band’s past pomp-pop excursions, its leader’s Beatles fixation, or the fact that this foray into dancy fare (keyboardist Richard Tandy referred to the album as Disco? Very!) was at all a digression from past glories.

Imagine, though, that you’re Jeff Lynne in 1979 (minus the aviator shades and perm, unless you really like perms). You’ve built towering castles of sound for nearly a decade, and played symphonic pop with the aplomb of McCartney and the sly mischievousness of Chuck Berry—your string-laden take on “Roll Over Beethoven,” in fact, was a hit (though it was more Wolfgang A. than Ludwig v., cuz Mozart was more likely to abscond across state lines with pretty underage lovelies than was Beethoven). Even as punk blew up and people like Johnny Rotten eyed you as if imagining your freshly boiled corpse slathered with mustard and placed between two slices of good rye bread, you made the ultimate plastic prog double album Out of the Blue, complete with a side–long “concerto.” You are an artist. Capital A-R-T—and the other letters.

But all anyone wants to do is dance. And not just to sway in the middle of a crowded arena, as “Can’t Get It Out of My Head” filters the air around them. There are lights and neck chains and polyester suits involved. They love the nightlife and feel they have to boogie.

Okay, fine. You have a great rhythm section in Bevan and Groucutt—guys who can approximate disco’s thump-pop and hi-hat hiss and who would never, ever, ever betray you. You can bring the strings in, more for flourishes than to carry the songs. You can make bridges—there will definitely be bridges. And breakdowns. You can do this. You’re Jeff-freakin’-Lynne. Disco? Very!

Plus, you know, if the Beatles were still around, they’d be making disco records—they’d almost have to.

(At this very moment, John Lennon, kneading bread dough in his Dakota apartment, a year and change left to live, experiences a sustained, stabbing pain in his spleen, which forces him to sit down. Meanwhile, Paul McCartney naps warmly in his seaside retreat in Hove, purchased with the royalties earned from the “Goodnight Tonight” single).

And so, Lynne and Co. created their stab at Bee Geedom, largely successfully. “Shine a Little Love” kicks off the record with thirty seconds of spooky keyboards and chimes that lurch into a rumbling, “Achilles Last Stand”-ish intro, which in turn slides into a thumpy dance groove. Lynne does his pasty British soul man thang over a prancing bass line and electric piano comping, leading into the gloriously ascending pre-chorus—a quick trip into the clouds, before the descent back to the dance floor (punctuated, as were many of the era’s party anthems, with a group of people yelling, “Woo!”).

“Shine a Little Love” is as perfect a dance single as one could expect from a British prog-pop band, and Lynne follows with a similarly high-quality midtempo ballad in “Confusion,” all cascading keyboards and acoustic strumming. It’s the kind of thing the Moody Blues—that other symphy Brit export—should have been doing all decade long. There’s really not a danceable moment here, unless it’s of the grasp-one-another-and-sway variety. Listening to it now—on vinyl, with speakers set to “Stun”—I hear low-mix layers of vocals I’ve missed, lo, these last thirty-odd years. They are gorgeous little things, and I am pleased to make their acquaintance.

“Need Her Love” slows things down even further, though the Abbey Road Side Two atmosphere is lovely, indeed. Side One ends with “Diary of Horace Wimp,” an “Eleanor Rigby” for Yvonne Elliman fans. A tale of the downtrodden chap who is yanked from his sad sack existence by a “voice from above” that chides him as badly as any of his daily acquaintances, “Diary” chronicles the week he rises above his nerddom and actually finds everlastin’ satisfaction with a pretty, pasty British lass. The comedic twist at the end of the song, though, is not nearly as funny as the bippity-boo-boo vocorder vocals that skip and prance through the entire song.

“Need Her Love” slows things down even further, though the Abbey Road Side Two atmosphere is lovely, indeed. Side One ends with “Diary of Horace Wimp,” an “Eleanor Rigby” for Yvonne Elliman fans. A tale of the downtrodden chap who is yanked from his sad sack existence by a “voice from above” that chides him as badly as any of his daily acquaintances, “Diary” chronicles the week he rises above his nerddom and actually finds everlastin’ satisfaction with a pretty, pasty British lass. The comedic twist at the end of the song, though, is not nearly as funny as the bippity-boo-boo vocorder vocals that skip and prance through the entire song.

Lynne returns to the dance floor out of the gate on Side Two, as “Last Train to London” thumps and shimmys, with perfect use of the E.L.O. strings, applied to the task of wooing a young lady back to ye olde flat after an evening of gettin’ down, Saturday Night Fever-style. It’s a terrific come-on, replete with mid-song harpsichord solo (gotta give the harpsichordist some, knowhumsayin’?). The gettin’-it-on gets serious with “Midnight Blue,” a sweet, post-wooin’, baby-makin’ track that features both the low-in-the-mix bassy vocals and the vocorder declamations, as well as Lynne’s manly falsetto. It’s the kind of song that the CD player repeat function was made for, to keep the mood going until the mighty-mighty goes nighty-nighty.

Since we’re talking about vinyl, though, we get one shot at “Midnight Blue,” and it ends at the intro of “On the Run,” a dinky mood-breaker if ever there wuz one. Actually, “On the Run” and “Wishing,” which follows it, are typical Side Two filler—placeholders for the listener’s attention until the big mama-jamma comes up.

Said jamma on Discovery is “Don’t Bring Me Down,” the album’s closing track, most popular song, and quite possibly E.L.O.’s most lasting hit. It’s a great song, but one built around a curiosity—the synthesized noise attached to the brief drum breakdown after the second verse. Two verses come before it; two verses and two choruses come after it, but those three and a half seconds are what people wait for, kinda like Homer Simpson at a Bachman-Turner Overdrive show. And when the song ends, you pick up the needle and play the song again, waiting for those three and a half seconds. You turn your volume as loud as you can stand, for those three and a half seconds; you cup the headphones closer to your ears, for those three and a half seconds. You risk the ire of your neighbors, family, and God Hizself, to crank it up for those three and a half seconds. The whole of recorded music prior to Discovery was merely the prelude to those three and a half seconds, and the whole of recorded music since those three and a half seconds has been a gradual comedown.

Jeff Lynne might have been a Wilbury; he might have shepherded Roy Orbison’s final words to the world; he might have turned two John Lennon demos into reasonably listenable songs; he might have written a “concerto” on Out of the Blue—but he will always be remembered as the man who made those three and a half seconds on “Don’t Bring Me Down.” The damn Beatles never did that.

Comments