My crushing cynicism about life cannot withstand the blunt-force power of certain phenomena that seem to exist purely to negate the cynic’s strength. I am impervious to baby photos, for example, but put me in the room with one of the little freshly baked humans, and I turn gelatinous. Web videos of cute animals doing funny things are legion, and I am unmoved by their “Aw shucks” sweetness and light (not to mention the intentions of their masters behind the camera). The guileless affection of a friendly dog (or that of my dour but affable cat, Winston)? I am unable to resist, and to return in kind.

My crushing cynicism about life cannot withstand the blunt-force power of certain phenomena that seem to exist purely to negate the cynic’s strength. I am impervious to baby photos, for example, but put me in the room with one of the little freshly baked humans, and I turn gelatinous. Web videos of cute animals doing funny things are legion, and I am unmoved by their “Aw shucks” sweetness and light (not to mention the intentions of their masters behind the camera). The guileless affection of a friendly dog (or that of my dour but affable cat, Winston)? I am unable to resist, and to return in kind.

The music of Kenny Loggins is the pop equivalent of a toothless infant’s smile, though I know that, as an infant is likely releasing excrement as he or she forms that teensy-weensy grin, there is much in the Loggins oeuvre that is greenish-brown and smelly. No matter. I am drawn to the sound of the man’s voice and many of the asthenic musings of his imagination. Not all, mind you—when Loggins takes the highway to the danger zone, I get off at the first exit. I don’t even much enjoy kicking off my Sunday shoes (in this case, house slippers—I’m not a church-goer) and cutting loose with him. And the less said about his unimaginable life (what my pals Jeff Giles and Jason Hare refer to as his “enema period”), the better.

No, I dig the dude in the matching orange shirt and slacks, strumming the shit out of a 12-string acoustic guitar, singing “I’m Alright” on one of the first handful of videos I saw on MTV (kids, the M in MTV used to stand for Music, not Mook or Miserable). I dig the guy who sang “Whenever I Call You Friend” with Stevie Nicks, and who co-wrote “This Is It” and “What a Fool Believes,” three AM radio staples of my childhood. I dig the man who displayed the power ballad prowess of “Meet Me Half Way” and “Forever” and who—with “If You Believe” and “I Would Do Anything” and “Too Early for the Sun” (all of 1991’s Leap of Faith, actually)—created the soundtrack of the early days of my courtship with the patient, charitable woman who later agreed to marry me.

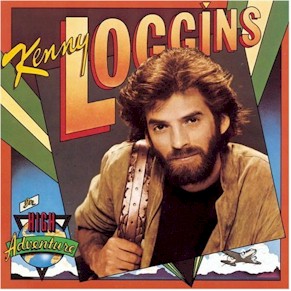

I dig the guy who dressed up like Indiana Jones on the cover of 1983’s High Adventure, and who rejected the original cover idea—a re-construction of his Keep the Fire cover, with the glowing orb in his hands replaced by Jim Messina’s still-beating heart, freshly ripped from the hapless Poco alum’s chest in a Thuggee cult ritual. High Adventure captured Loggins in a transitional phase, between the modest hitmaker of the Seventies (both solo and in partnership with Messina) and the soundtrack superstar of the mid- and late Eighties. Though it lags in spots late on Side Two, it is in many ways as perfect an adult contemporary pop record as you can hope for, blessed with expert playing, gorgeous production, and a brace of songs full with emotional heft and mature concerns.

I dig the guy who dressed up like Indiana Jones on the cover of 1983’s High Adventure, and who rejected the original cover idea—a re-construction of his Keep the Fire cover, with the glowing orb in his hands replaced by Jim Messina’s still-beating heart, freshly ripped from the hapless Poco alum’s chest in a Thuggee cult ritual. High Adventure captured Loggins in a transitional phase, between the modest hitmaker of the Seventies (both solo and in partnership with Messina) and the soundtrack superstar of the mid- and late Eighties. Though it lags in spots late on Side Two, it is in many ways as perfect an adult contemporary pop record as you can hope for, blessed with expert playing, gorgeous production, and a brace of songs full with emotional heft and mature concerns.

Things kick off with “Don’t Fight It,” one of Loggins’ finest flat-out rock songs, due in no small part to the presence of Pat Benatar’s hubby/guitarist Neil Geraldo and co-writer/duet partner Steve Perry, stepping out from his day job in Journey. The song begins with Loggins extolling the pleasures of strong drink:

Live long enough you’re bound to find

Moonshine’ll make a man go blind

Never can tell what the brew will do

But there’s times you’ll wind up feelin’ so fine

Yummy. One might surmise Perry would follow with a verse about finding the perfect Chablis, or the problems one has getting a good Beaujolais Nouveau for the Thanksgiving Day table. Nope. Instead, he takes a page from the Glenn Frey school of sexual politics:

Some women seem to have a knack

They’ll turn you on and leave you flat

Never can tell who’s playin’ for keeps

So tell me now what’s holding you back

I know your heart can take it

Bitches ain’t shit, he seems to say. They only keep a man from doing his manly duty, which of course consists of getting laid and rocking out. The song really cooks, though, thanks to Giraldo, on loan from Benatar’s band and boudoir; the binguna-bunguna- binguna-bunguna guitar riff and studiously sloppy solo are a cut above the polished flair usually present on Loggins records.

Bitches ain’t shit, he seems to say. They only keep a man from doing his manly duty, which of course consists of getting laid and rocking out. The song really cooks, though, thanks to Giraldo, on loan from Benatar’s band and boudoir; the binguna-bunguna- binguna-bunguna guitar riff and studiously sloppy solo are a cut above the polished flair usually present on Loggins records.

I have two favorite moments in the song—one I’ve always assumed was Perry, and one that is definitely Perry, in all his great Perryness. As Loggins finishes his half of the second verse—the line “I turn up the music ’til it’s shakin’ the sky”—somebody off-mic (I like to think it’s Perry) yells in assent, a “Yeah!” or some such thing. It goes by quickly; when the song was played on the radio, you probably couldn’t hear it. It’s a little slip of a moment, a rare bit of improvised expulsion on an otherwise carefully plotted track.

The second moment is also in the second verse—Perry’s penultimate line, “There’s nothing wrong with raisin’ some hell,” in which he stretches the word hell into two syllables (heh-hell), almost chuckling it, with evil intent. It’s as though he felt he could induce hell-raising with the mere inflection of his voice. Earlier attempts at this—think of “Lay It Down” or “Escape,” from Escape—were seriously deficient (he was always better at lady-wooin’, with his hippie Sam Cooke shtick). This one, though, just about works.

Hell-raising or no, “Don’t Fight It” catches Loggins and Perry just before they uncorked their solo mojos on such popular concoctions as “Footloose” and “Oh Sherrie,” both of which would follow within a year. This is where the magic got started.

K-Log follows the opening rock move with “Heartlight,” which is not a reference to E.T. (as was Neil Diamond’s hit of the same name), but a paean to the Heartlight School, a now-defunct private institution in Los Angeles. According to Loggins’ liner notes, a student at Heartlight, when asked what he liked most about the school, answered, “I like the love.” Loggins blatantly stole the poor kids’ words, like the rat bastard that he is (kidding) and turned them into the first line of the song, following it with a conga-punctuated interpretation of what it might have been like to learn something there:

I hold the hand

I walk with the teacher

We welcome in the mornin’

Singing together

Heartlight apparently treated singing as a vital part of the curriculum (the school’s chorus features prominently in the song), particularly in the morning. The evenings, though, were given to something more fabulous:

Stand in the dark

Oh, and I’ll light a candle

And then we’ll dance in the moonlight

Until the sunrise

Intentional or not, Loggins makes Heartlight sound like the coolest boarding school/summer camp in the world, with the singin’ and dancin’ and love-likin’. I’m going to guess they had a shitty football team, though.

“I Gotta Try” is the first of three co-writes with

that made it on the record; this one had appeared on McD’s first solo album in an almost identical version. Really, it sounds a lot like the other K-Log/McD collabs—blue-eyed soulful verses that leap into brilliant pop choruses. We got the same deal with “This Is It” and “What a Food Believes,” and it would happen again, a few years later, with “No Lookin’ Back,” and even a few songs later, on Side 2, with “Heart to Heart,” in which co-co-writer David Foster sneaks in his Fosterness (not to mention a Fosterific key change). “Heart to Heart,” as befitting the pedigree of its authors (not to mention the shiny reputations and uniformly perfect stylings of its players) is a perfect slice o’ adult contempo seriousness. It’s about surviving the painful stretches of a relationship, possibly to renew one’s love and commitment, possibly to call the whole thing off. The chorus presents the conundrum:

Does anything last forever?

Does anything last forever?

I don’t know

Maybe we’re near the end

Darlin’, how can we go on together

Now that we’ve grown apart?

Well the only way to start

Is heart to heart

This is serious shit; nobody’s having any fun here. Nobody’s getting laid or rolling a number or snorting a line (well, maybe someone was snorting a line—Toto, if you recall, was collectively elected president of Bolivia for two terms in the early Eighties, and several of los presidentes play on High Adventure). This ain’t something to be enjoyed, living through all this (or watching your parents live through all this, which supposedly is what fueled Loggins’ lyrics). “One by one, we’re collecting lies,” Loggins sings. “When you can’t give love, you give alibis.” That’s not fun. The players aren’t having fun. Michael McDonald isn’t having fun. David Foster is having fun, but that’s because he got to put a key change in the song.

Again, this is serious shit. Or at least you’d think so, until you look at the liner notes and see the credit “‘Artistic Debris’—David Sanborn.” Ah, David Sanborn, session man extraordinaire, provider of Bowie’s “Young Americans” hook and countless “that was him?” moments on records from the Seventies. Sanborn, who lets fly with a tremendous high-register sax solo that provides “Heart to Heart” with its release, one that speaks to the seriousness of the subject matter. David Sanborn. Artistic Debris.

When you think about it, though, you can’t help but realize that these fuckers were having a blast. They were playing on a surefire hit, and all were likely getting paid two or three times union scale for the privilege. Artistic debris, my ass. They probably even told each other jokes between takes.

The song that sounds like it was the most fun is “Swear Your Love,” a deceptively breezy bit of Logginsia that blows by you at 100 miles an hour and leaves your hair messy the rest of the day, though the verses and chorus sound as though they’re attached with Erector set parts. For such a light-sounding song, the sentiments expressed in the lyrics venture into some heavy cynicism, which I applaud, but which is an odd stance for the man whose initial popularity came from his song about Winnie the Pooh. Perhaps Loggins and wife Eva Ein (who co-wrote the song) were secretly planning the divorce they’d embark upon before the decade was out, cuz matrimony takes a street-level beatdown:

You see your diamond ring,

You see your diamond ring,

I’m here to say that doesn’t mean a thing

Without your love

And if that’s all we got then take it off, tear it off …

… I know a lady in Spokane

She thought that happiness would find her when

She caught a man, security second-hand

She got her diamond ring

It’s sad to say that was the only thing

“She thought that happiness would find her when she caught a man?” Damn, that’s cold. I mean, I get the point, that loveless marriages are bad, but still—”security second-hand?” That’s ice cold. That’s Steve-Perry-channeling-Glenn-Frey cold. The first chorus (which is money, like all great choruses are) further piles on the snark:

Swear your love say you don’t need no diamond baby

If some piece of paper’s keepin’ us together, I ain’t buyin’ it baby

Multiple K-Logs work the high harmony, so it sounds great blasting out of your Trans Am while cruising the strip on a Friday night, but the breeze of the music is belied by the ill wind blowing through the lyric.

The proto-hair metal of “If That’s Not What You’re Looking For” and the plastic rock of “It Must Be Imagination” sound, smell, and taste like filler, and serve only to delay the listener from encountering the beautiful K-Log/McD album closer “Only a Miracle.”

Strings—both real and synthesized—slip us into the song, and it sounds like—God help me—a Dan Fogelberg intro, so much so that my arms broke out into little itchy hives the first time I heard it. Just as I was going for the calamine, though, Loggins opened his mouth, and out came this:

I’ve always said that I believe that anything can happen

I’ve always said that I believe that anything can happen

Lately I’ve been wonderin’ if that’s really true

For a boy, time can be a lovely dance, then suddenly the music can fade

Leave the man alone and dreamless

Until he only sees that he’s used up all his chances after all

‘Til now only a miracle could do to save the man I’ve turned into.

Won’t somebody let me know, where’s my miracle?

Whew, I thought then, with my mother’s words echoing in my head (“Don’t scratch it; it’ll only spread!”). True dat, I think now. “Only a miracle could do to save the man I’ve turned into”—when you look in the mirror and the face staring back at you is the face of someone who has let you and others down in so many sundry ways; when that man hits a patch when he can do nothing right, or correctly, or properly, or successfully; when that man repeatedly steps into the many holes he’s dug for himself. That man is the sad-sack schlub in Lionel Shriver’s novel So Much for That, and Jonathan Tropper’s new one (One Last Thing Before I Go), and every novel Richard Russo has ever written. Those are the books that reflected man reads the most, because the protagonists are so much like him, and if they can find redemption—their miracle—then there is hope for him.

Loggins deepens the monologue in the second verse, slowly unfolding the real reason for the song:

Love it always seemed so easy

Just like a child who plays with imaginary friends

I could see the face of someone I believe but only in the words of a song

Then she came along and got me dreamin’

That’s when it began and when I held you, I held a miracle in my hands

Until now, only a miracle could do

I’ve found the boy I was in you

You’ve come to let me know there are miracles

The schlub finds redemption, in the love of a good woman and, especially, the birth of their child—the “miracle” about which the song is written. The moment captured is a magical one, indeed—that first time you lift the newborn, making sure to support his head, bringing him toward your body, for comfort and warmth. He’s been taken from the safety of the womb, brought outside into cold, antiseptic environs, breathing air, hearing noise, passed from hand to hand. His life is just starting; yours will never be the same. In the rush of fears and concerns and mistakes and things you’ve said and things you should have said and done and prayers you’ve made and oaths you’ve sworn and everything positive and negative that you’ve ever thought about yourself, all of it going by in a maelstrom powerful enough to suck you in and knock you over—there comes a moment of clarity. It doesn’t last long—you’re in the storm’s eye, and its tail end will come around and hit you again—but there it is, all around you, all of it centered on this life, this child. Childbirth is biological; our species has done it for millennia. But the birth of this child—this one, yours, the one breathing and crying in your arms—is nothing short of miraculous. That’s what Loggins captures here, his voice fluttering and soaked in orchestration.

It’s a moment that can sap the power of even the hardest cynic. It gets me every time.

Comments