Last year saw a number of albums released by artists whose best days one might have imagined might be behind them—strong work, work that musicians so long in the tooth have little business making. Dion’s album New York is My Home showed The Wanderer applying what is in my opinion the greatest voice rock and roll ever produced, to a set of old-school rock and blues tunes, and pulling it off with skill and feeling. Emitt Rhodes broke a 43-year silence with Rainbow Ends, an adult pop album that landed on my best-of-the-year list, among many others. Even the Monkees—aided by Adam Schlesinger, Rivers Cuomo, Ben Gibbard and a host of other writers and performers of relatively recent vintage (as well as Popdose alum John Hughes in the executive producer’s chair)—turned in a record (Good Times) whose best tracks can sit easily with the best things they did in their prime.

The Monkees, people!

Considering the number of beloved artists we lost last year, it occurs to me how tightly we should be holding on to our elders, how closely we should embrace new work from them. When we lost David Bowie (just over a year ago, if you can believe that), one could not help but turn one’s attention to other iconic figures of similar age, and recognize the odds were good that their demises would be sooner, rather than later, relatively speaking. McCartney is 74; Dylan is 75; Mick and Keith are each 73. Hell, Springsteen is 67, and in spite of a recent spate of four-hour concerts, 67 is still 67 (sure, John Lee Hooker played until he died at 88, but I don’t recall him crowd-surfing during those shows).

The fact is, the elders are in their twilight; for some of them, it’s later in the evening than others. When they speak, we should listen.

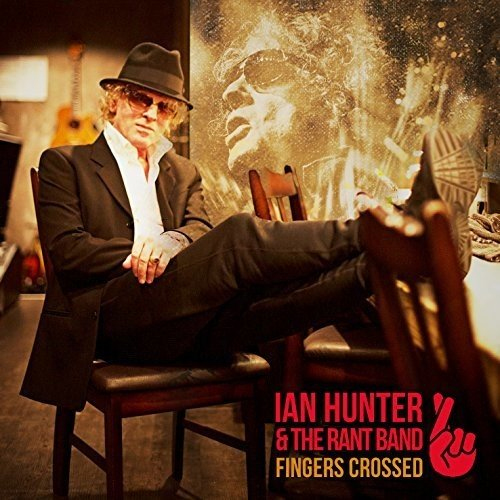

Every few years, Ian Hunter, 77, gathers his Rant Band and puts together a set of straight-up rock and roll songs, and my God, we should all be grateful for that. Last year’s Fingers Crossed finds him sounding energetic and vital as ever, from front to back.

Every few years, Ian Hunter, 77, gathers his Rant Band and puts together a set of straight-up rock and roll songs, and my God, we should all be grateful for that. Last year’s Fingers Crossed finds him sounding energetic and vital as ever, from front to back.

Hunter’s swagger is intact in the opener, ”That’s When the Trouble Starts,” which, with its sharp guitars and Hunter’s gritty vocal, sounds like the best Talk is Cheap outtake Keith Richards never had. His complaint that we’re all ”heading down the sewer of reality” dovetails nicely with Side Two’s ”Stranded in Reality,” an alien’s perspective of life on this here third stone from the sun. This particular spaceman is more than a little touched by earthlings’ cynicism, particularly the American strain of it, as he marvels at how little he likes about the place. ”They still believe in fancy tales,” he sings, ”and lots of ammunition.” He must have crash-landed somewhere near where I live.

The best tracks on Fingers Crossed are the ones in which Hunter looks back at his past, whether it’s the countrified, album-closing ”Long Time”—an exercise in memoir as rock song—or the flat-out rock of ”Ghosts,” a loud-but-reverent rave-up Hunter wrote about a trip to Sun Studios in Memphis, where some of the earliest rock and roll was recorded. ”Why don’t you put the needle down,” he sings in the great refrain, yearning to hear his heroes play, even as he stands in the very place where they made the records whose grooves helped form him and his art.

Hats must be removed and prayers lifted to the heavens for ”Dandy,” Hunter’s elegy for Bowie. The lyrics skitter close to maudlin—with a few too many references to Bowie songs for my taste—but the overall result is one of heartfelt respect and, dare I say it, love, for both the man and his music.

There’s one verse that moves me deeply, each time I hear it—

Dandy, the world was black and white

You showed us what it’s like

To live inside a rainbow

Hunter really gets to the heart of the effect Bowie had on him and his contemporaries—taking them out of the drab, boring days of their youth and surroundings and turning that fuzzy, grayscale existence into the sharpest technicolor vision imaginable. Bowie was his enchanter, his compass, and also his friend and collaborator. Hearing ”Dandy” late in 2016 conjured up the days after Bowie’s death for me, a bittersweet thing, to be sure, but also a healing thing. Ian Hunter’s mourning was one that many others could share.

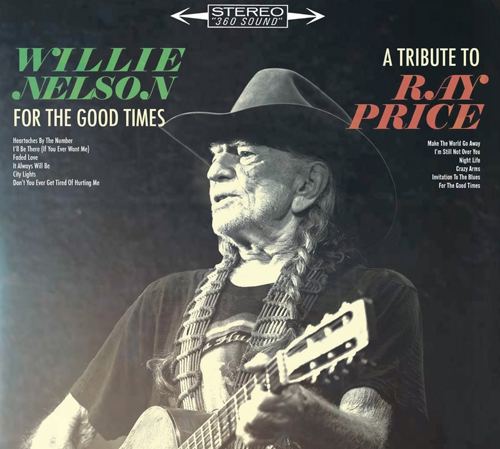

If you’re Willie Nelson and you’re mourning a friend, perhaps you don’t write a song that encapsulates the breadth of your feelings. Perhaps, instead, you pay tribute to your friend by singing the songs he sang, just the way he sang them. Such is the case with For the Good Times, a tribute to Ray Price, an early benefactor of Nelson’s and close friend, who died in 2013.

Back in the early Sixties, when Nelson was a struggling songwriter in Nashville, Price recorded several of his songs (most notably ”Night Life,” which became something of a theme song for Price) and installed Nelson as his band’s bassist. Over the course of a 50-year friendship, they played together countless times and recorded three albums together (including the wonderful San Antonio Rose, in 1980).

Back in the early Sixties, when Nelson was a struggling songwriter in Nashville, Price recorded several of his songs (most notably ”Night Life,” which became something of a theme song for Price) and installed Nelson as his band’s bassist. Over the course of a 50-year friendship, they played together countless times and recorded three albums together (including the wonderful San Antonio Rose, in 1980).

Price had a velvety voice that was sophisticated and twangy, equally at home with a country shuffle and a string-laden ballad. Nelson pays tribute by staying close to the classic arrangements that Price and his producers employed to clothe that voice, often employing the fine Western swing all-star collective the Time Jumpers to bring the arrangements to life, with rich, soulful playing.

What is initially jarring is Nelson’s own voice. When he sings, it’s still unmistakably, inimitably him, but there is a worn quality that has been pronounced these last few years—a fading, like a picture left too close to a light for too long. The details can still be discerned, but what remains is weaker for the time spent too close to that intensity. When Johnny Cash made his last couple American records, one could hear the toll the years had taken on him; it was in the frailty of his voice, yet the ”Cash-ness” of it—his phrasing, his accents—remained intact. Nelson, at 83, is in a similar situation.

He can still deliver, though, and when he does, there’s no mistaking you’re in the presence of one of the greats, even though the experience is not the same as it once was. Take “Heartaches by the Number,” the first track on the record. The Time Jumpers apply the fiddles and the pedal steel, and the song shuffles the way a good country shuffle should. Nelson is definitely there, tucked a back a bit in the mix, and you notice his pace and phrasing are different than you might be used to hearing in other versions of the song; there are more micro-pauses, and the notes don’t settle in the back of his throat quite like they once did. Vince Gill’s harmony vocal on the chorus fattens the tone, and when it does, you can hear what’s missing, the layer of sound that’s not quite present when Nelson is alone at the mic.

That recognition returns on the next track, ”I’ll Be There (If You Ever Want Me),” one of the standouts on Nelson and Price’s San Antonio Rose, where the two traded verses and sang harmonies effortlessly. On the new version, Nelson is hitting the notes, but he doesn’t enliven the song as much as simply perform it, letting the arrangement (for the Time Jumpers and background voices) carry the day. And while Price is absent, Nelson’s approach reveals his spirit to be very present—it sounds like a Ray Price song, thanks to the reverent reading Nelson provides.

This happens again throughout the record. ”Make the World Go Away” is another example of the arrangement being the star, with the abundance of background voices and creamy strings (courtesy arranger and conductor Bergen White), contrasting against Nelson’s worn delivery. It’s a gorgeous rendition, but the best part may well be the opening ten seconds, in which Nelson delivers a preamble on Trigger, his worn gut-string guitar, sans any other accompaniment, except the sound of his own breathing.

Beauty abounds in “I’m Still Not Over You”—when Nelson sings ”That feeling’s still the same,” it’s almost a whisper, and it makes you feel like he means it. ”It Always Will Be” has an almost cinematic scope (replete with a flute solo), and Nelson’s voice—on the higher notes, in particular—turns back the clock at least 20 years.

But the clear highlight is the title track—the elegiac Kristofferson cover that closes the album. Price had one of his biggest hits with the song, back in 1970; Nelson and producer Fred Foster incorporate a Seventies-style electric piano with the acoustic guitar and pedal steel in the song’s early moments, as Nelson sings ”Let’s just be glad we had some time to spend together,” and his friend’s ghost hovers over the room. It all builds with background voices and strings into that heartbreaker of a chorus, and you can’t help but get chills as it does.

It hits you (if it hasn’t hit you before this moment) that For the Good Times is not just a tribute album, but a gift—a gift of music Nelson might have simply made on his own and offered up to the cosmos, hoping it would find Price somewhere on the other side of the horizon. That he recorded it and took such care with it is a gift from Nelson to those of us with the heart and smarts to listen; it’s a testament to the love one man has for another, and for the music and memories that bound them.

And yes, the performances here may contain an unstated acknowledgment of time and what it can and cannot do. It can take our bodies—obviously, because Price is not present—and it can also weather and thin our voices, as it has to Nelson’s.

But there are also things time cannot do, at least not yet, and one of them is tell Willie Nelson—or, for that matter, Ian Hunter—to lie down. We should be grateful for that, for every day we have these men, these artists, still with us, still interested in and capable of making art. This may be their twilight, but they’re greeting that twilight with souls still bursting with songs, and with guitars still in their hands.

Comments