In the summer of 1980, between a short stint in college and a longer (27-year) stint in the New Jersey State Police, my cousin Chuck held a job pumping gas at the 10S Service Area on the Jersey Turnpike. It was mostly night work, and during his shifts he doubtless encountered nocturnal nomads of every stripe and social position, from vacationers to gangsters to working folk, to party-goers racing the dawn. On occasion, he also got to wipe the windows, check the oil and pump petrol for someone he recognized from the movies or TV or his album collection.

One night, a tour bus pulled into the station, and as he filled the great steel horse with diesel, Chuck asked the driver whether the vehicle was carrying Jackson Browne, who he knew had played the nearby Garden State Arts Center that evening. The driver said it was, and invited my cousin to climb inside and meet the band.

Now, Chuck claims to not remember what he saw inside the bus (and I believe him—we humans only have so much space in our brains, and all those Phillies statistics have to go somewhere), but one can just imagine what went on in there—these were, after all, the kings of Laurel Canyon at the height of their powers (Browne’s Hold Out had just been released, and was about to take him to Number One on the album chart). I imagine the dimly lit path lined with comfy seats, the air sweet with the smoke David Lindley was blowing from the hookah built into the four-neck, 32-string bouzouki he was playing. Over on the other side, Russ Kunkel was working on his comb-over and his three-year plan to steal Carly Simon from James Taylor. Bill Payne and Bob Glaub were each getting comfortable with a young lady, Payne by recalling his days in Little Feat, Glaub by complaining about the other guys making fun of him because he wasn’t Leland Sklar (who, had he been in the bus, would have been giving shelter to at least three groupies, in his beard).

Now, Chuck claims to not remember what he saw inside the bus (and I believe him—we humans only have so much space in our brains, and all those Phillies statistics have to go somewhere), but one can just imagine what went on in there—these were, after all, the kings of Laurel Canyon at the height of their powers (Browne’s Hold Out had just been released, and was about to take him to Number One on the album chart). I imagine the dimly lit path lined with comfy seats, the air sweet with the smoke David Lindley was blowing from the hookah built into the four-neck, 32-string bouzouki he was playing. Over on the other side, Russ Kunkel was working on his comb-over and his three-year plan to steal Carly Simon from James Taylor. Bill Payne and Bob Glaub were each getting comfortable with a young lady, Payne by recalling his days in Little Feat, Glaub by complaining about the other guys making fun of him because he wasn’t Leland Sklar (who, had he been in the bus, would have been giving shelter to at least three groupies, in his beard).

All the way in the back of the bus, likely behind a curtain of turquoise and aquamarine stones, perched atop a bed strewn with rose petals and surrounded by five nubile 19-year-olds in togas, sat Jackson Browne himself. In one hand, he held a mirror tile containing lines of a white powder, and in the other hand a book of Zen proverbs. I can imagine him looking quizzically at Chuck and saying to him, ”Sitting quietly, doing nothing, spring comes and the grass grows by itself.”

I imagine my cousin looking quizzically back at him. The hell is he talking abou—

”Nobody rides for free,” imaginary Browne sang, and the five nubile 19-year-olds responded, ”Nobody, nobody.” At which time imaginary Chuck likely nodded and slowly turned, then walked back through the curtain of tiny stones, through the Lindley haze, and back out to the diesel pump.

The reality of my cousin’s moments on the bus more than likely involved Browne sitting having a beer with his band (though still making fun of Bob Glaub), or some such innocuous thing. But listening to the bulk of Browne’s output by the turn of that decade could easily lead one to believe he spent a good bit of time pondering the deep imponderables and counting the ways in which our lives are sliced open and emptied by love’s impermanence, nature’s vengeance and God’s indifference.

The reality of my cousin’s moments on the bus more than likely involved Browne sitting having a beer with his band (though still making fun of Bob Glaub), or some such innocuous thing. But listening to the bulk of Browne’s output by the turn of that decade could easily lead one to believe he spent a good bit of time pondering the deep imponderables and counting the ways in which our lives are sliced open and emptied by love’s impermanence, nature’s vengeance and God’s indifference.

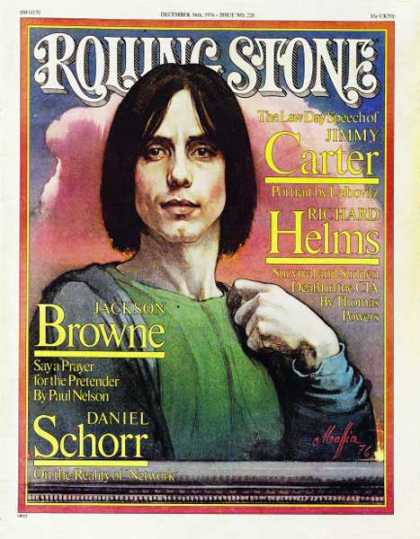

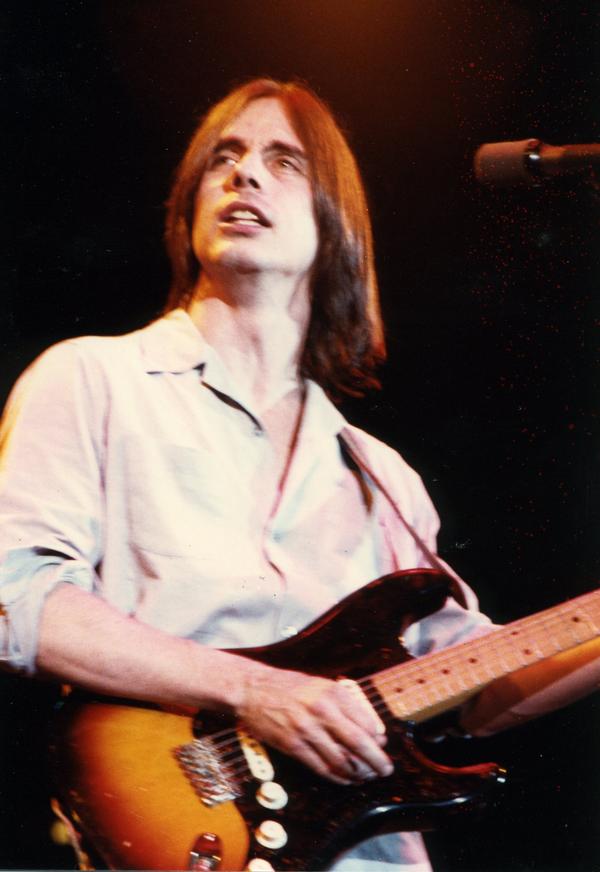

His first two records were really good—Jackson Browne had ”Doctor My Eyes” and ”Rock Me on the Water” and ”Jamaica Say You Will”; For Everyman had ”Redneck Friend” and ”Take It Easy” and the immortal ”These Days.” Browne’s next three albums, though, were reputation-making, era-defining, son-you’re-gonna-play-amphitheaters-for-the-rest-of-your-life singer/songwriter manifestos, though mostly quiet ones. This was a three-year stretch of creative bloom in an era in which sensitive singer/songwriters came up out of the bars and coffeehouses like wheat comes out of the ground—in great bulk and very closely resembling the stalk standing next to it.

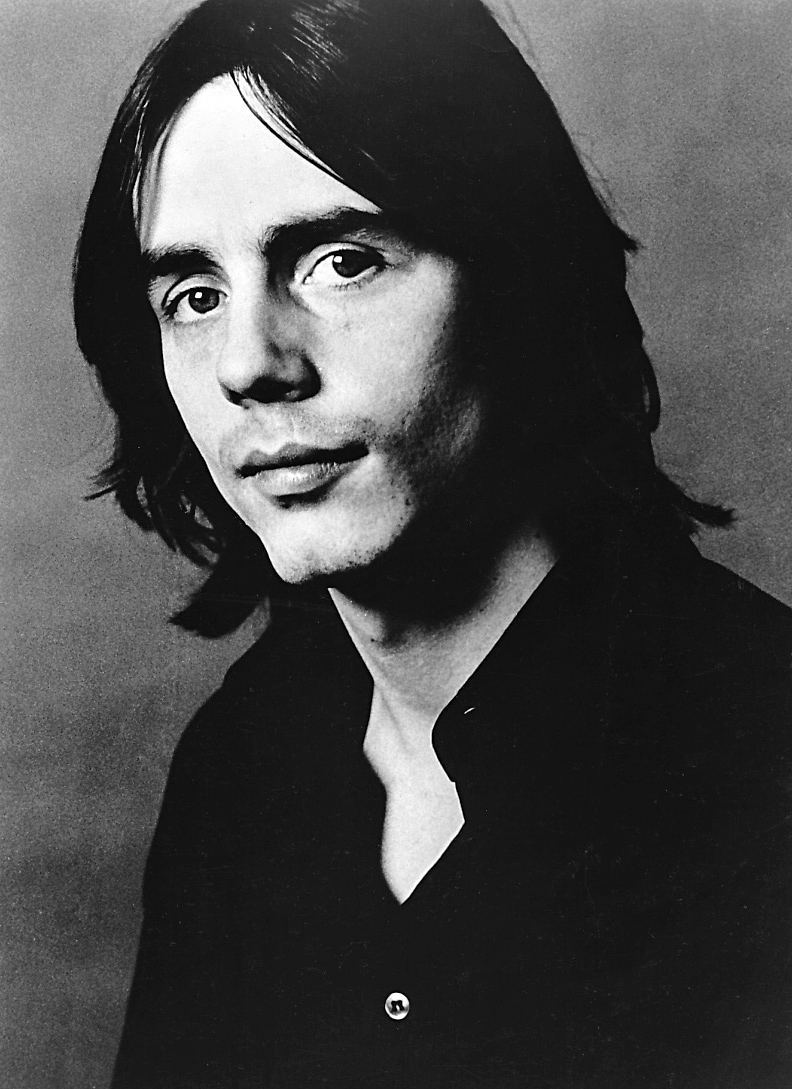

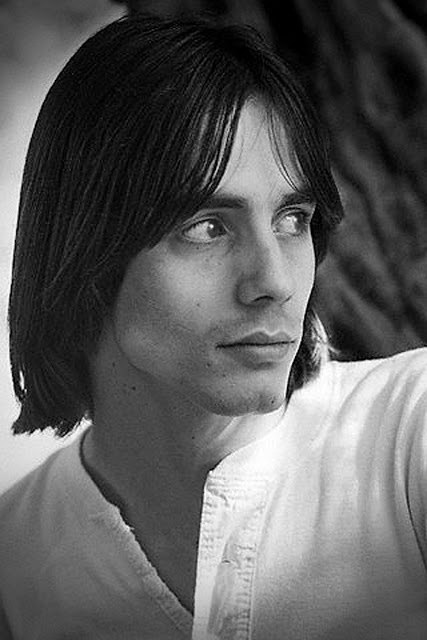

What set Browne apart, other than the handsome smoothness of his face and his carnal knowledge of Nico, Laura Nyro and Joni Mitchell, was the caliber of his writing, and the way the musicians under his command helped him craft those ponderings into artistry of the highest order. He had the cream of the session musician crop playing his compositions in the studio and on the road, making the ballads float cloud-high and the rock songs zip cleanly, like on a Linda Ronstadt record. This was a damn good thing, because the songs themselves could have sunk heavily in weaker hands.

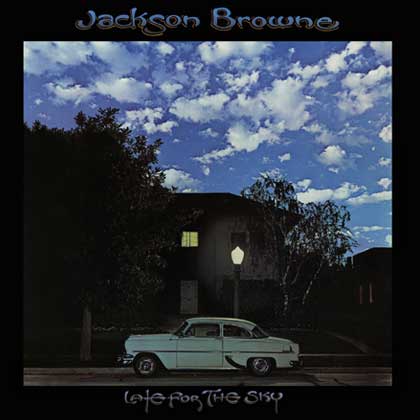

Late for the Sky, released in 1974, was a towering achievement in both morose earnestness and earnest morosity. To this day, it stands as an example of the Laurel Canyon ethos of the Seventies, with lyrics that dig deep into the post-hippie psyche and music played with polish and professionalism. And more polish.

Late for the Sky, released in 1974, was a towering achievement in both morose earnestness and earnest morosity. To this day, it stands as an example of the Laurel Canyon ethos of the Seventies, with lyrics that dig deep into the post-hippie psyche and music played with polish and professionalism. And more polish.

The title track is a perfectly paced reflection on love’s dissolution. An all-night conversation with a soon-to-be-former lover leads to the recognition that the end is near, and has been coming for a good long while. ”How long have I been sleeping?” he asks, but after rubbing his eyes, he understands—”I know I’m alone / And close to the end / Of the feeling we’ve known.” The song builds slowly to the climax of the final verse, when the instruments fall away, leaving just Browne’s voice to sing the song’s title, the only time he does so in the song. It’s a kind of sigh of resignation; one can easily imagine him letting it out, then turning and walking away from the microphone, out of the vocal booth, out of the studio, and across the street, into the scene pictured on the album’s cover—an homage to Rene Magritte—a dark home nearly consumed by a beautiful blue sky.

You’ll recognize other songs on the album—”Before the Deluge” closes the record; ”Fountain of Sorrow” is on there, too. So is ”For a Dancer,” a meditation on seizing the day, on the occasion of a friend’s funeral, complete with a lovely harmonizin’ choir of Don Henley, John David Souther and whoever else was hanging out in the studio that day. Don and John reappear on ”The Late Show,” giving a kind of responsive reading to Browne’s paean to finding one true love in a big, big world.

You’ll recognize other songs on the album—”Before the Deluge” closes the record; ”Fountain of Sorrow” is on there, too. So is ”For a Dancer,” a meditation on seizing the day, on the occasion of a friend’s funeral, complete with a lovely harmonizin’ choir of Don Henley, John David Souther and whoever else was hanging out in the studio that day. Don and John reappear on ”The Late Show,” giving a kind of responsive reading to Browne’s paean to finding one true love in a big, big world.

My favorite song on the record might be its most aberrant. ”Walking Slow” is the boxer’s feint right in order to deliver a left hook. It’s a straight-ahead, uptempo thumper in which Browne professes to be ”feeling good,” because he’s ”all alone and … got no place to go.” This, we find is bullshit; he’s got a woman at home who he describes thusly: ”Sometimes we forget we love each other and we fight for no reason.” He doesn’t know what he’ll do if she leaves him, but one gets the feeling he’s going to find out soon enough.

Late for the Sky has all the marks of a classic Seventies singer/songwriter album—smart songcraft, squeaky clean playing and a dead-on earnestness about the subjects under discussion in the songs. I place it with Sweet Baby James, Tapestry and maybe Still Crazy After All These Years on some Troubadour Rushmore for that period (you might also squeeze in Harvest, Blue, Christmas and the Beads of Sweat, Moondance and Blood on the Tracks, but that’s a lot of mountain).

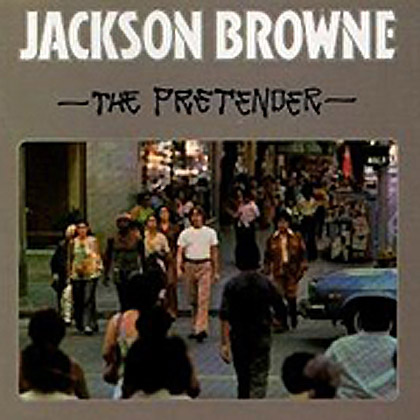

The Pretender (1976) had all of Late for the Sky’s earnest energy, but, at 35 minutes long, it feels more compact in form and execution. It starts with ”The Fuse,” a song whose chief object of menace is unstated, and thus open to interpretation. When Browne sings ”It’s coming from so far away, it’s hard to say for sure / Whether what I hear is music or the wind through an open door,” the listener doesn’t know what it is, and the remainder of the song gives few clues – death? destruction? impending doom? The angst is plain, and the rumination on time’s passage (“Through every dead and living thing / Time runs like a fuse”) is penetrating.

The Pretender (1976) had all of Late for the Sky’s earnest energy, but, at 35 minutes long, it feels more compact in form and execution. It starts with ”The Fuse,” a song whose chief object of menace is unstated, and thus open to interpretation. When Browne sings ”It’s coming from so far away, it’s hard to say for sure / Whether what I hear is music or the wind through an open door,” the listener doesn’t know what it is, and the remainder of the song gives few clues – death? destruction? impending doom? The angst is plain, and the rumination on time’s passage (“Through every dead and living thing / Time runs like a fuse”) is penetrating.

Browne’s wife, Phyllis Major Browne, committed suicide in the middle of the album’s recording, leaving Browne to raise a young son on his own and lending poignancy to the two songs on the album that focus on the relationship between fathers and sons. ”The Only Child” sees a father imparting advice to his offspring, with a healthy dollop of cynicism:

Whatever you might hope to find

Among the thoughts that crowd your mind

There won’t be many that ever really matter

You almost hear the kid whispering, ”You can say that again,” as he bounces on Papa’s knee. That song is followed by ”Daddy’s Tune,” the flip side of that conversation, years after the father-son relationship has soured, perhaps after the old man has died. The son reflects on his role in that relationship’s problems:

Daddy what was I supposed to do?

I don’t know why it was so hard to talk to you

I guess my anger pulled me through

The odd thing about the song is its arrangement—the first two verses are delivered in ponderous Brownean ballad mode, but this approach gives way to a horn-driven, almost celebratory blast of soul (or soul-ish) music to continue the pondering at a much more sprightly tempo. This second part of the song seems almost bolted onto the first part; the incongruity is jarring (credit is probably due to producer Jon Landau, on holiday from turning Bruce Springsteen from New Dylan to New dos Passos).

This is particularly so when one considers the pure perfection of the album’s most beautiful moment. ”Sleep’s Dark and Silent Gate” continues the relationship thread from ”Walking Slow,” on Late for the Sky, though where the earlier song moves with a straight rock rhythm, ”Sleep’s” is almost motionless, awash in piano and strings that sweep where the earlier song bounced. The love he had found has indeed left him, and the quiet moments before fitful rest are awash with regret. The killer lines come at the end of the first verse, as the full weight of his melancholy descends—

Never should have had to try so hard

To make a love work out, I guess

I don’t know what love has got to do

With happiness

But the times when we were happy

Were the times we never tried

The last two lines are delivered with a kind of heartbroken resignation that can crack the listener open, just as the singer himself has been cracked open. On the Jackson Browne sadness scale of 1 (”I’m very sad—like, James Taylor sad”) to 10 (”Dear sweet Jesus, I’m going to die of heartache—my heart literally hurts”), those two lines register somewhere north of 12.

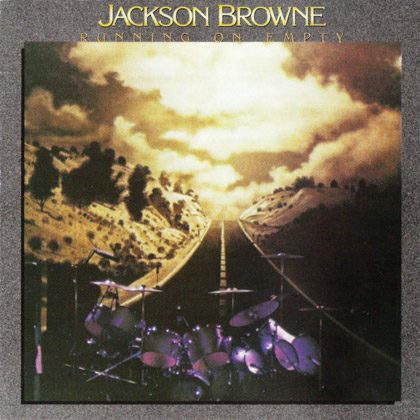

”Love Needs a Heart,” from Running on Empty (1977), follows that dour strain to its conclusion, as the singer’s regret turns to motion. Here, it’s clear he is the one who’s done the leaving (”Leaving behind the life that we’d begun / I split myself in two”). To get away from that regret, he takes off, but no length of time on the road enables him to escape; he sees the pain in her eyes everywhere—”They’re behind each flashing city light.” It’s a sight he cannot elude, a sadness he cannot outrun.

”Love Needs a Heart,” from Running on Empty (1977), follows that dour strain to its conclusion, as the singer’s regret turns to motion. Here, it’s clear he is the one who’s done the leaving (”Leaving behind the life that we’d begun / I split myself in two”). To get away from that regret, he takes off, but no length of time on the road enables him to escape; he sees the pain in her eyes everywhere—”They’re behind each flashing city light.” It’s a sight he cannot elude, a sadness he cannot outrun.

Motion is a central theme throughout Running on Empty—if not the first concept album about a band on the road, then certainly one of the finest. Recorded onstage, in hotel rooms and on tour buses, the album offers a peek into the idle moments musicians experience when not onstage—from the illicit pleasures and lasting damage described in ”Cocaine” to the dawdling and glad-handing in the cover of Danny O’Keefe’s ”The Road,” to the humorous coulda-been/shoulda-been story in ”Rosie,” which ends with the singer alone in his hotel room, doing the five-finger shuffle. ”The Load Out” pays tribute to the road crew that sets everything up and tears everything down, and it’s followed on the record by a take on Maurice Williams and the Zodiacs’ ”Stay,” which is played on classic rock radio to this day.

But Browne also uses the road as a way to attach some sort of measurement to his life, on the album’s title track. He wonders where the time has gone, and what he’s done with himself, how the years have changed him. ”Everyone I know, everywhere I go / People need some reason to believe,” he sings, before practically shouting, ”I don’t know about anyone but me.” It’s as if he’s attempting to put some distance between the artist who spent time searching for answers to Big Questions, and the one who simply wanted to get onstage and play rock and roll.

Or it could be that he’s found that there are no clear answers. The key lines come in the last verse—

I look around for the friends that I used to turn to pull me through

Looking into their eyes I see them running too

What are they running from? Age? A world they don’t understand? The ennui of their eventual offspring? Or are they afraid of what will happen if they stop running, if their motion ceases? Musicians used to life on the road often have trouble re-acclimating to life off the road. Sometimes, though, the habits they develop or nurse while in motion do follow them back, often to deleterious effect. Sometimes there’s simply no home to go home to, literally or figuratively—what is there to do but keep running?

What are they running from? Age? A world they don’t understand? The ennui of their eventual offspring? Or are they afraid of what will happen if they stop running, if their motion ceases? Musicians used to life on the road often have trouble re-acclimating to life off the road. Sometimes, though, the habits they develop or nurse while in motion do follow them back, often to deleterious effect. Sometimes there’s simply no home to go home to, literally or figuratively—what is there to do but keep running?

Running on Empty was the last of Browne’s great Seventies records; Hold Out would follow in 1979, but for the first time, Browne seemed to falter lyrically, particularly when he turned his lens outward to street scenes that seemed inauthentic, as on ”Disco Apocalypse” and ”Boulevard.” Though the exquisite ”Of Missing Persons” and the title track still resonate today, too much of the album sounded empty; well played, but empty. I kept buying his records for years, but tended to only find one or two or three songs on each that moved me. That’s not to say that there haven’t been some extraordinary moments—a great Jackson Browne playlist must contain middle- and late-period tracks like ”In the Shape of a Heart,” ”Anything Can Happen,” ”I’m Alive,” ”Lawless Avenues,” ”Sky Blue and Black,” ”Time the Conqueror” and ”Birds of St. Mark’s.”

I do think he hit on something special on those early albums, though, when he had youth and earnestness and the best musicians around on his side, and a whole lot of time ahead of him. When he bade his audience good night at the end of Running on Empty, he left a bit of that something behind—an important bit.

Or maybe he just took it out to the tour bus and forgot it there. Groupies in togas can be distracting.

Comments