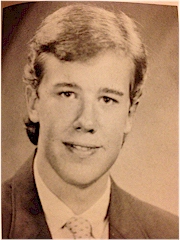

See that kid on the right? Smooth-faced, hair neatly parted, wearing the sport coat he hates? That’s me. The old fart down at the bottom of the page is me, too, but I don’t want to talk about him yet. I want to talk about the kid. I want to talk about 1988.

See that kid on the right? Smooth-faced, hair neatly parted, wearing the sport coat he hates? That’s me. The old fart down at the bottom of the page is me, too, but I don’t want to talk about him yet. I want to talk about the kid. I want to talk about 1988.

Goddamn, man—1988. High school, senior year. In the grainy, squiggly VHS tape that is my memory of that time, we were full of kinetic energy, tethered in place by parents and teachers and, yes, one another—with a sense of duty to be fulfilled by putting in our hours, and parroting back what needed to be repeated in order to be remembered, later to be forgotten. Kinetic energy with nowhere to go—that’s potential energy, and potential was what we foresaw for ourselves, in various degrees, and what those older and presumably wiser than we were saw for us, too.

One was our baccalaureate speaker, who didn’t even know us. “Today we dream dreams,” he told us ad nauseum, “Tomorrow, we live them.” I don’t know that I ever dreamed the life I lead now, and that’s okay—I was almost 18 then, and I wanted to be in radio, spinning and back-announcing records like Casey Kasem and Johnny Fever, like I’d done in my bedroom when I was a kid, like I’d do for a few years in college, before recognizing the reality of radio as a low-paying career of constant motion, and later giving it up.

Didn’t know that back then. It just seemed like fun, something I could look forward to doing. Potentially. Kinetically. Looking forward was what we did, when we weren’t focused on the moment we were in, and after that the next one, then the next one. The future was amorphous; any attempt to structure it at that point was foolhardy, parents and teachers be damned.

Kinetic energy, tied at the knees. You fall down a lot. You lift yourself back up (or, if you’re fortunate, you have others who can help you). When you have 17 or 18 years behind you and God knows how many ahead, you speak before you know what you’re talking about. You barrel into things head-first, because you can. You love—God, you love with more passion and emotional recklessness than you ever will again. You learn. Eventually, you learn.

If you’re smart—or if you’ve been unwillingly transient throughout your childhood—you stop from time to time, look around you, take stock and lock away a given scene or place or taste or person or kiss or sound or song, so you can remember it, so that years down the line, it will move you again. It will move you again when you least expect it to move you, when it sneaks up on you, taps you on the shoulder, and hits you in the jaw, hard, when you turn around. It will move you again because it’s imprinted deep within you; because when you’re moved, the air you breathe tastes and smells like it did then, and the room you’re in is the room you were in then, and the one you shared the moments with then is sitting next to you now, a chimera, an illusion, with an echo for a voice, and the spell lasts for as long as you can make it last, until you realize it’s all ephemeral, and then it dissipates; she fades into the ether, and the song’s final refrain fades away.

Some of our friends didn’t make it. Scott never saw graduation, taken out in a car accident that left him forever potential, and left the rest of us feeling a whole hell of a lot less immortal. Cancer took Eddie at 37. Tami died a couple years ago—another car crash—and left a husband, two daughters, and innumerable broken hearts in her wake. There have been others too soon gone, friends who once walked among us in the halls and beside the lockers, laughing, acting up, or just getting through it all.

Illness. Accidents. Dangers we never considered then.

Those remaining have fanned out. I kept in touch with a few, and, until recently (cough … Facebook … cough), was too busy with my own little corner of the universe to give much thought about the others. For many years, I thought it unnecessary to get back in touch with people, to, as I’ve noted previously, interrupt pleasant echoes of then with awkward small talk today.

But you know what? I was wrong. It’s a good thing to reconnect with old friends, even with secondary and tertiary players from that period. We probably have more in common now than we used to have. We grew up. We made it. We are now the age that our parents were then. We have spouses or significant others, kids, homes, hobbies, aches, pains, problems. Swim meets, soccer games, recitals. Victories, defeats. These are good things to share, good conversations to have.

But you know what? I was wrong. It’s a good thing to reconnect with old friends, even with secondary and tertiary players from that period. We probably have more in common now than we used to have. We grew up. We made it. We are now the age that our parents were then. We have spouses or significant others, kids, homes, hobbies, aches, pains, problems. Swim meets, soccer games, recitals. Victories, defeats. These are good things to share, good conversations to have.

But they’re also bittersweet. Before relatively recently, I only rarely pondered the passage of time; my M.O. was always mere acceptance. Someone would say, “I can’t believe it’s been x years since [insert occasion],” and my typical response was, “Yeah, it’s been about that long.” Nonchalance. Our timelines are, by definition, linear things—we started way over there, then [insert occasion] happened back there, and now we’re here. Here we are. Que sera, sera. Shit happens, as they say, and happens often.

And though it is so clichÁ© I cannot believe I’m admitting it, I now ponder time often. I’ll be 43 next month, so that probably has something to do with it. And though 43 isn’t one of those milestone birthdays we throw big parties for, it has been 20 years since I graduated college (that one, last December, was a gut punch). And next week, my high school classmates (or some of them, at least) will gather to celebrate 25 years since we all shuffled onstage at the Hershey Theater and shuffled off our adolescent coils, leaving the hallowed halls of our alma mater for good, and bidding it good riddance.

(I will not be among the revelers, though I had every intention of joining in the fun; I will instead be driving back from a rare extended-family vacation, which I’m sure I’ll one day tell you all about, if I am fortunate enough to survive it).

That old Seger lyric comes back at me—”Twenty years—where’d they go? / Twenty years—I don’t know / I sit and I wonder sometimes / Where they’ve gone.” Add five years and stir, look into the glass, and you might just see overweight, bald, gray-bearded me sitting in my home office, Beck’s tallboy in hand, thinking about that kid at the top of the page and wondering what he might’ve thought of this middle-aged man, whether where I’ve wound up and what I’ve done and who I am have been worthy of that energy from 25 years ago, whether what I’ve done with that energy is all I could have done with it. Some days—many days—I wonder if I have any of that energy left, or whether I might be able, by some means, to conjure up some of it again.

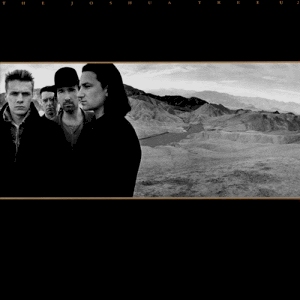

When I hear “Where the Streets Have No Name,” the opening track on U2’s The Joshua Tree, I feel some of that energy come back to me. How many long, aimless drives (back when gas was, like, a buck a gallon) began with that song? Too many to count. How many times did I shout along with the spoken part in “Bullet the Blue Sky” (“And he’s peeling off those dollar bills / One hundred! Two hundred!”)? How many times did I sing the harmony part in “In God’s Country?” how badly did I beat the steering wheel in my old ’78 T-Bird, pounding out Larry Mullen’s beat from “Exit?” U2 was the biggest band on the planet my senior year of high school. Hearing this record—any of it, really, in spite of the time gone by and the ubiquity of its most famous tracks—immediately transports me to that period, consciously or otherwise.

When I hear “Where the Streets Have No Name,” the opening track on U2’s The Joshua Tree, I feel some of that energy come back to me. How many long, aimless drives (back when gas was, like, a buck a gallon) began with that song? Too many to count. How many times did I shout along with the spoken part in “Bullet the Blue Sky” (“And he’s peeling off those dollar bills / One hundred! Two hundred!”)? How many times did I sing the harmony part in “In God’s Country?” how badly did I beat the steering wheel in my old ’78 T-Bird, pounding out Larry Mullen’s beat from “Exit?” U2 was the biggest band on the planet my senior year of high school. Hearing this record—any of it, really, in spite of the time gone by and the ubiquity of its most famous tracks—immediately transports me to that period, consciously or otherwise.

Who knows how much time lies ahead? The best we can do is count up what’s behind us, and brace ourselves for whatever happens next. I hope my old friends have a good time next week. Maybe, on a good day—on the very best of days—we’ll recognize that energy from then moving through us now. It could happen next week, or next year, or tomorrow. Maybe it won’t happen at all, and we’ll just have to contend with what we are and where we are, in this instant. Maybe in the end, that’s all we really need, and being okay with that is the very best we can ask for.

Comments