In an era full of quirky bands, XTC may have been the quirkiest.

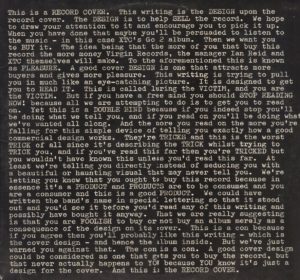

Their debut album featured primary singer/songwriter Andy Partridge leering at the Statue of Liberty amid musical settings designed to simultaneously build upon and satirize pop and punk. Their second album was a favorite of record-store browsers like me for its cover, a Monty Python-esque essay in plain typography informing us all that this is a RECORD COVER whose DESIGN is to help SELL the record.

Their debut album featured primary singer/songwriter Andy Partridge leering at the Statue of Liberty amid musical settings designed to simultaneously build upon and satirize pop and punk. Their second album was a favorite of record-store browsers like me for its cover, a Monty Python-esque essay in plain typography informing us all that this is a RECORD COVER whose DESIGN is to help SELL the record.

Keyboardist Barry Andrews, whose off-the-wall organ flourishes had added to the hilarity of the first two albums, departed at that point. Enter Dave Gregory, sometimes a keyboardist but more frequently a guitarist from the George Harrison melodic school. And bassist Colin Moulding hit his songwriting groove with Making Plans for Nigel, a skewering of British parents forcing their kids through a regimented childhood and pre-ordained adulthood.

By the early 80s, they were ready for MTV with Senses Working Overtime, which alternated sparsely arranged verses with a sprightly chorus (all together now: ”1, 2, 3, 4, 5! Senses working …”).

Then came the meltdown. Explanations have varied over the years, but all we really need to know is that Partridge was no longer able to play on stage. At the height of their careers, XTC quit performing live.

Fortunately, these were the days in which a band could still earn a living making these things called ”albums.” While XTC regrouped without a drummer (Terry Chambers had an Australian girlfriend, and without live gigs, there really wasn’t much point in staying), they also formed a psychedelic side project called The Dukes of Stratosphear and settled into a nice groove releasing albums for a loyal cult following buoyed by a few ”hit” songs on alternative radio.

Then they recorded a series of masterpieces.

Skylarking benefited from the discipline imposed by producer Todd Rundgren. It’s in some ways the rural answer (not that XTC’s base of Swindon is a tiny town, but the band was influenced by the fields around it as surely as R.E.M.’s early work reflects agricultural northeast Georgia) to Dark Side of the Moon — a set of musings on life and death with transitions between songs and moods.

And still, the decision-making was odd. Initial pressings of the album omitted the agnostic’s lament Dear God, a classic mix of Partridge wit and anger perfectly arranged with atypical rhyme schemes and brooding acoustic guitar — the bass notes under an A minor chord go A / F / G / F#, creating an ominous, uneasy atmosphere. It’s an alt-rock standard that barely saw the light of day.

Oranges and Lemons was XTC’s The White Album, a mixture of pop and more diverse styles pushed along by Moulding’s agile bass lines and guest drummer Pat Mastelotto on his way to King Crimson glory. My personal favorite is the chaotic Across this Antheap, a witty and poignant depiction of a society too distracted by ”work” to address those in need. ”The fur is genuine but the orgasm’s fake,” chortles Partridge before he takes liberties with the rhyme scheme: ”We’re spending millions to learn to speak porpoise / while human loneliness is still a deafening noise.”

This album also found Partridge reveling in parenthood. The opener, Garden of Earthly Delights, is a remarkably optimistic tour of the world for his children, including such helpful advice as ”Just don’t hurt nobody — less of course, they ask you.” Next up is parent Partridge pledging to make up for his lack of education with a big heart in Mayor of Simpleton, which actually topped the U.S. Modern Rock chart and got airplay on our local ”Skynyrd and Zeppelin 4EVER” station in North Carolina.

So if you had to pick a band that would gaze upon a rotting jack o’lantern and immediately think of heads on spikes at Traitor’s Gate, then turn the whole thing into a tale of a Jesus/JFK figure inspiring people but being murdered by the cynical powers that be, then use that as the lead single for an album called Nonsuch, you’d have to say XTC. Read the story at Chalkhills.com, which goes into vivid detail on scores of XTC songs and will destroy your productivity for the day.

On its surface, Pumpkinhead is rather cynical. A compassionate and charitable man (”showed the Vatican what gold’s for”) develops a following (”emptied churches and shopping malls”), and those who prefer the status quo of the oligarchy (”But he made too many enemies / Of the people who would keep us on our knees”) respond by questioning his sexuality (”Peter merely said / Any kind of love is all right”) and then crucifying him (”had him nailed to a chunk of wood”).

But like a lot of Partridge songs, this is deceptively hopeful. It has a sprightly setting, as American Songwriter notes:

While Bob Dylan may have been an inspiration to Partridge when writing, he and his band played the song more as an energetic romp than a balladic dirge, with a recording featuring booming drums, jangly guitar, and frisky harmonica.

The general populace in this song is receptive to Peter’s ”peace, love and understanding” message. Yes, the rulers have him killed, but then there will always be more Peter Pumpkinheads — in all of us. ”Hanging there he looked a lot like you, and an awful lot like me.”

We may not need one massive Peter Pumpkinhead. We need a little Peter Pumpkinhead in all of us.

So, this Halloween, why not leave your jack o’lantern out a bit longer than usual? Maybe we’ll be inspired. (Or maybe the neighborhood deer will have a nice snack.)

Comments