1988’s Brian Wilson is one of my very favorite albums. Around the time of its release, I read in Rolling Stone or Variety or maybe both that a biopic was in the works, with William Hurt as Wilson, who had come out of a foggy epoch of mental illness to record what was his first solo album after all those Beach Boys hits of the 60s, and Richard Dreyfuss as Eugene Landy, the unconventional live-in psychologist who got him into shape for the task. “Good casting,” I thought…and that was the last I heard of the project, which, as we now know, was premature, to say the least.

1988’s Brian Wilson is one of my very favorite albums. Around the time of its release, I read in Rolling Stone or Variety or maybe both that a biopic was in the works, with William Hurt as Wilson, who had come out of a foggy epoch of mental illness to record what was his first solo album after all those Beach Boys hits of the 60s, and Richard Dreyfuss as Eugene Landy, the unconventional live-in psychologist who got him into shape for the task. “Good casting,” I thought…and that was the last I heard of the project, which, as we now know, was premature, to say the least.

Fun, fun, fun, the recording was not, as Landy, who in 1992 was exposed as a charlatan and a quack of the kind peculiar to Southern California, pretty much whipped the hapless, overmedicated Wilson into shape for the recording sessions. Love & Mercy, a Brian Wilson biopic at last, goes into this tormented history, with John Cusack as Wilson and Paul Giamatti as Landy. But it’s only half the story, as it goes in and out of the 80s to the 60s, with Paul Dano as Wilson in his Beach Boys prime.

Or, rather, at the crest of the wave. Wilson, restlessly creative and spurred by the innovative sounds of the Beatles, dives headlong into the creation of Pet Sounds, to the confusion of the Boys and the skepticism of his father (Bill Camp), a fearsome, pipe-smoking authoritarian recently replaced as their manager. Envelope-pushing experiments in the studio do lead to the group’s biggest hit, “Good Vibrations,” but by then Wilson, as sensitive as an egg in its shell, cracks; he can hear only the music in his head.

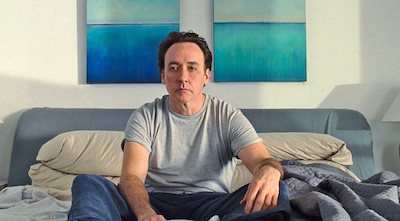

In the 80s, Wilson, a wispy, tentative figure always accompanied by Landy and his entourage, buys a Mercedes from Melinda (Elizabeth Banks), a salesperson who is somewhat reluctantly drawn into a relationship with the shadowy legend. Showing real mettle as their quirky romance deepens, Melinda uncovers Landy’s shady dealings and seeks to free Wilson from his regimen of drugs and surveillance. Cusack is credited as “future Brian,” billing that only become clear with the film’s final, haunting shot, which brings Wilson’s life full circle.

“Great Man” biopics become more hollow with each passing Oscar season, as square pegs like Alan Turing (The Imitation Game) and Chris Kyle (American Sniper) are bashed into round holes. Paced by Chadwick Boseman’s searing performance as James Brown in last summer’s Get on Up, musician biopics are holding their own–we don’t expect saints, and we’re not suffocated by official portraiture as the great artistry is explored. Love & Mercy excels in its studio scenes, as Wilson stubbornly, taxingly tries to extract that elusive new sound from his head, in sequences that are aurally illustrated by montages of Beach Boys and other music and audio brilliantly arranged by Oscar winner Atticus Ross (The Social Network).

“Great Man” biopics become more hollow with each passing Oscar season, as square pegs like Alan Turing (The Imitation Game) and Chris Kyle (American Sniper) are bashed into round holes. Paced by Chadwick Boseman’s searing performance as James Brown in last summer’s Get on Up, musician biopics are holding their own–we don’t expect saints, and we’re not suffocated by official portraiture as the great artistry is explored. Love & Mercy excels in its studio scenes, as Wilson stubbornly, taxingly tries to extract that elusive new sound from his head, in sequences that are aurally illustrated by montages of Beach Boys and other music and audio brilliantly arranged by Oscar winner Atticus Ross (The Social Network).

Consequently, the film favors Dano, who is spectacularly well cast as Wilson, who flowers, then disappears, right before our eyes. I can understand why producer and second-time director Bill Pohlad, from a script by Oren Moverman (an Oscar nominee for The Messenger) and Michael Alan Lerner, wanted to split the role, to show how Wilson was forced to shed one skin for another, and to reinforce a theme of doubling–Camp, a great stage actor who made a memorable appearance in Birdman, and Giamatti, masking the predator beneath layers of therapeutic concern, excel as the monster fathers, and if I’m not mistaken multi hyphenate-of-the-moment Banks (looking uncannily like Melanie Griffith) plays Wilson’s mother, a vaguer figure in his life, in one quick scene. Seeming to take his cue from Peter Sellers in Being There (1979), Cusack has neither the resemblance nor the character arc. He does, however, have one great moment, trying to negotiate a street corner as Wilson tries to regain basic skills after years of coddled isolation, and while not as radical as the multiple Bob Dylans in I’m Not There (2007) the rationale at least grapples with the limitations of swaddling a young actor in wigs and padding that might detract from his performance.

With numerous surviving family members are thanked in the closing credits, Love & Mercy doesn’t feel compromised. (The staff will be relieved to know that Popdose hate object Mike Love comes off rather poorly as the band disintegrates.) Nor is it overly celebratory, given the traumatized life at its center. It’s honest, heartbreaking, beautiful–and a gem.

Comments