”I feel that in my photographs there is a trust given by the artists. When I point the camera at somebody, there is covenant, and I will not violate that trust” — Jim Marshall

One of my favorite possessions is Not Fade Away, the book by photographer Jim Marshall. I received it for my birthday from my brother in 1997 and since then, the hardbound collection of black and white stills has been taken down from the bookshelf once or twice a year. I spend a week or so leafing through Marshall’s candid, intimate photos, rereading his recollections and marveling at the artistry of each shot. There is an effortless quality to Marshall’s photography that is difficult to pull off. He was a master.

birthday from my brother in 1997 and since then, the hardbound collection of black and white stills has been taken down from the bookshelf once or twice a year. I spend a week or so leafing through Marshall’s candid, intimate photos, rereading his recollections and marveling at the artistry of each shot. There is an effortless quality to Marshall’s photography that is difficult to pull off. He was a master.

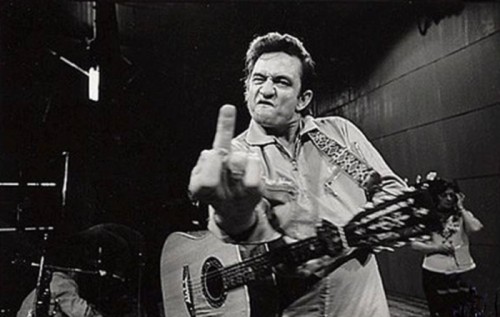

Rock and roll and music lost a legend on Wednesday when Jim Marshall passed away at the age of 74. You may not recognize his name, but if you’re a fan of popular music, then you’ve seen his work: The Jefferson Airplane standing in a circle staring down at the camera; Otis Redding pleading into the microphone, onstage at the Monterey Pop Festival; The Beatles rushing out on to the field of Candlestick Park for their last concert ever; Bob Dylan rolling a tire down a New York City sidewalk; The Allman Brothers laughing in front of their gear, posing for the cover of their seminal album, At Filmore East; Keith Richards on the verge of tipping out of his chair during the Exile on Main Streets sessions, cigarette in mouth, guitar in hand; Johnny Cash flipping off the camera, backstage at San Quentin prison.

During the early years of rock n roll, when the music was still shaping into an art form, Marshall was there to document the highs and lows with his trusty Leica cameras. Born in 1936, Marshall bought his first camera in high school and photographed the beat scene in his hometown of San Francisco. After a stint in the Air Force, Marshall had a chance encounter with the legendary John Coltrane that resulted in nine rolls of pictures. Those photos of Trane led to paying gigs in New York, working with Dylan and Ray Charles. In the late ’60s, Marshall returned to California as the hippie scene was exploding. He was on hand to witness and photograph the emergence of the Airplane, Buffalo Springfield, Janis Joplin and the Grateful Dead.

The artists Marshall worked with trusted him and became his friends. In return, he made these legends more human. To teenagers sitting in their bedrooms or basements, studying the photos on album covers or published in the likes of Rolling Stone, Marshall fueled the rock n roll dream letting the dreamers dream, ”Hey, I can do that; I can find a way to express myself through words or music or images.”

He never saw his work as just a job; it was his life. Like the men and women who were his subjects, Marshall was an artist first and foremost. Because of that, he refused to compromise and was unafraid of the assholes who tried to handle him and control the images of the musicians. As the music industry changed and managers and agents began dictating exactly how an artist should be photographed, Marshall balked. ”I care so much about the music business…” he said. ”I won’t be a part of the pack. I will not work that way… I won’t shoot just two songs at a concert. They wouldn’t be Jim Marshall pictures.”

In his life, Marshall collaborated on over 500 album covers and had lately worked with such artists as John Mayer, Ben Harper and Velvet Revolver. In addition to Not Fade Away, he also published five other books, including the recently published, Match Prints, a collaborative project with his friend and fellow famed photographer, Timothy White.

Marshall’s photographs are alive with the spirit of the people he was shooting. When they’re posing for camera, his subjects are playful and relaxed; when his subjects are unguarded and unsuspecting, you can see the trust they had in the man behind the camera. In today’s polished world of publishing, it is rare to see stars allowing themselves to be portrayed as anything other than celebrities. Now that Jim Marshall has left us, it will be even rarer.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=61ec553d-ada9-4860-9bbe-97db098c841c)

Comments