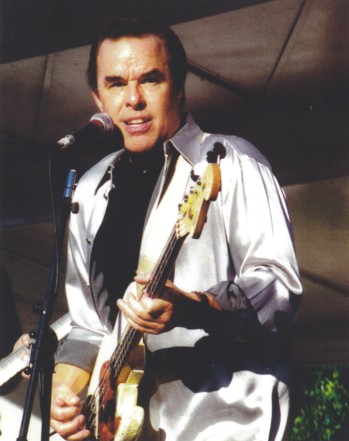

Famed bass players the likes of Brian Wilson and Will Lee have all flipped their instruments of choice in tribute to Phil ”Fang” Volk, best known as the grinning bassist of 60s rock band Paul Revere and the Raiders.

Famed bass players the likes of Brian Wilson and Will Lee have all flipped their instruments of choice in tribute to Phil ”Fang” Volk, best known as the grinning bassist of 60s rock band Paul Revere and the Raiders.

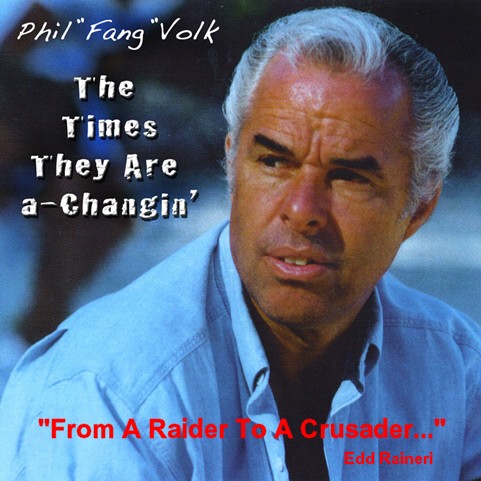

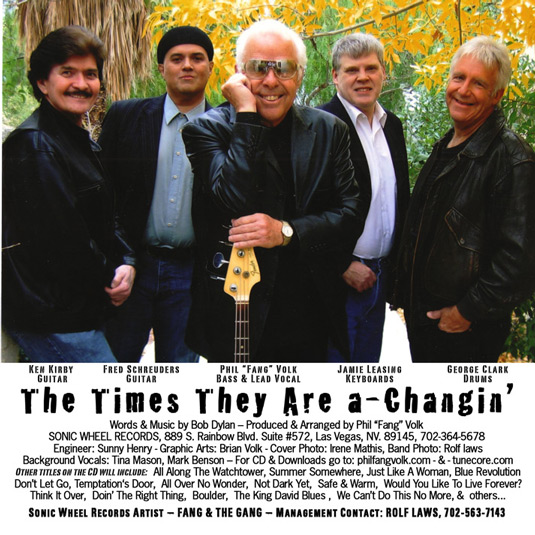

Today, ”Fang” is back on the scene with a new single, his reinterpretation of the revered Bob Dylan touchstone ”The Times They Are A-Changin’.” The song, which Volk calls ”the most important piece of music I’ve done in a long time,” has undergone a major makeover.

Released on May 1, the five-and-a-half minute rendition sounds as if it could be a lost bonus track from a Killers album (Volk’s voice effortlessly — and oddly — conjures that of Killers’ front man and fellow Las Vegas resident Brandon Flowers). It ends with a special ”secret message” meant to drive home the overarching sentiment of the song, and samples the Chambers Brothers’ ”Time Has Come Today” in subtle but evident background shouts.

Dylan purists beware: you won’t hear any jangly acoustic guitars or whiny assertions here. Instead, ”Times” is given the full rock n roll treatment, complete with reverberating guitars, forceful spoken-word verses, and a driving backbeat. All of which is meant to package it to appeal to a whole new generation.

”Times” has taken Volk from ”a Raider to a crusader” in the opinion of Edd Raineri of ”The Beatledd Fab Four Hour” radio program, who, according to Volk, also paid him a huge compliment by stating that Volk ”picked up where John Lennon left off” regarding the social and political implications of the single.

”I’m thinking wow, I do have a big responsibility to live up to,’” Volk says, ”because even though it’s only rock n roll and I love it, I’m still dead serious about it. The message is so poignant and relevant for our day, even more than it was in the 60s.”

The choice, he says, to utilize a Bob Dylan song to demonstrate and perpetuate his message was easy. ”Dylan was the perfect platform to get people’s attention because people respect Dylan.”

Reactions to the song have been largely positive, reports Volk, aside from one comment on Amazon from a user that questioned the ability to improve upon and add significance to a Dylan song. ”I’m thinking, wow, this thing is open to interpretation, my friend,” Volk says of his reaction to the comment.

”It’s still a magnificent song. It hasn’t lost anything. In fact, I think it’s gained quite a bit. Maybe it sounds bogus or cocky or arrogant to say that, but I think I’ve added something valuable to it. I think I’ve given it a fair and respectful treatment…an honest, personal reading.

”My job was to unravel some of the mysteries, break some of the codes and maybe violate some of the longstanding traditions that some of the Dylan faithful have held onto for, really, no apparent good,” he explains. ”Dylan music needs to be heard.”

And there’s no time like the present. Volk’s inspiration for recording the Dylan classic was the chaotic state of the world. ”Forty-eight years [after the song’s release], the 60s are being repeated in almost a more tumultuous way. People are suffering all over the world and there’s so much upheaval and so many revolutionary things happening. It’s very apparent that people want a better life and they want an end to terrorism and they want an end to things that are causing life to be so difficult and painful. There are solutions and you just have to keep your eyes and ears open and listen for something that has the ring of truth.

And there’s no time like the present. Volk’s inspiration for recording the Dylan classic was the chaotic state of the world. ”Forty-eight years [after the song’s release], the 60s are being repeated in almost a more tumultuous way. People are suffering all over the world and there’s so much upheaval and so many revolutionary things happening. It’s very apparent that people want a better life and they want an end to terrorism and they want an end to things that are causing life to be so difficult and painful. There are solutions and you just have to keep your eyes and ears open and listen for something that has the ring of truth.

”A song like this could easily become the voice of millions, because this is what people are experiencing every day in the real world, and that’s why the song is so significant. It’s a universal message for humanity.”

Volk’s history with Dylan’s musical modus goes back way before Robert Zimmerman ever set foot in a New York cafÁ©. After witnessing Elvis Presley’s performance on ”The Ed Sullivan Show” in the late 50s, a pre-teen Phil begged his parents for a guitar and that Christmas, his wish came true. Bewitched by the ease of playing the three or four chord melodies, he immediately began learning folk songs.

”Obviously I owe a big debt of gratitude to my parents for training me and cultivating this gift in me and teaching me,” Volk says. ”They really promoted my gift, my singing, my dancing, my guitar playing. They bought me equipment [and] they made sure that I could follow through on these dreams.”

Volk credits his mother, a singer, dancer, and former high-wire acrobat, with teaching him how to sing. It was also her who encouraged Volk to record his first songs inside a trailer at a local carnival a few months before his third birthday.

”I kind of got a quick design of where my life was going [that day]. Suddenly, my musical journey began with a bang, it began with hearing my voice that was recorded with a microphone and played back to me through speakers.”

Later, his childhood recording would find its way onto a track by Volk’s post-Raiders creation Brotherhood (under the nom de plume of Friend Sound) called ”Child Song.” Volk says that when he played the song for his mother, she broke down into tears, a memory that still manages to choke him up.

”My mom knew that I had this gift for singing,” he says, ”and she wanted to cultivate it. I’m so grateful that she had me go through this experience of recording a song at such an early age…it stayed with me all my life.”

Growing up in Nampa, Idaho, Volk began to nurture not only his burgeoning career as a musician, but also some pretty impressive vegetables — at age nine, he raised the largest zucchini in town. Little Phil and his six siblings took ballet, tap and gymnastics, and later, he excelled at sports, including football and track.

He also followed the local music scene intensely. When a fellow named Paul Revere rolled into town with his popular northwest dance band and performed at the high school variety show, Volk was electrified by what he saw. Even though he was too young to attend any of Revere’s official dances, he became determined to join the rock scene.

The following year, after the family relocated to the capital city of Boise, Volk joined the Chancellors, which quickly became the top rock act in the area. However, after Volk missed a gig in order to get a good night’s rest prior to a varsity track meet (at which he won two gold medals, he proudly adds), he was exiled from the group.

Luckily, a friend, Drake Levin, invited him to join his group, the Sir Winston’s Trio, as a bassist. Levin and his family had moved to Boise from Chicago a few years earlier. He and Volk became close and together developed their inner showmen. ”Drake and I used to dance a lot on our own when we practiced,” says Volk, ”and we did a lot of stuff like that, [just] some steps in our own band.”

In the Trio, they also traded bass licks and duties. It was Volk’s first experience with the instrument that would become his signature.

One day, while appearing on a local dance show in Boise, the members of the band made a fortuitous discovery: Paul Revere and the Raiders were performing that evening at a small club called the Crazy Horse. For Levin and Volk, who was finally old enough to go inside and see the show, the chance to see Paul Revere and the Raiders in action was too good to pass up.

After the Raiders’ set, Revere told the Trio that he liked what he saw on the dance show. He offered to hire them at the club, but, because it was a dance club, required them to find a drummer. Finding no other immediate option, they requested the use of Revere’s drummer, Mike ”Smitty” Smith.

”When you think about the irony,” says Volk, ”how fortuitous and providential that was. Here’s Drake, Smitty’ and Fang’ playing together as a band for one week in 1963, [in] Paul Revere’s nightclub.” Later, the three, along with Revere and lead singer Mark Lindsay, would constitute the iconic lineup of the band.

Now a quartet, the Trio changed its name to the Surfers and became prominent on the local rock scene. However, in the summer of 1963, Volk departed for college at the University of Colorado, and Drake was snatched up by Revere to serve as lead guitarist of the Raiders.

At college, Volk kept up his musical chops by playing guitar in his fraternity band. He also received his first introduction to Bob Dylan, who had burst forth from the Greenwich Village basket houses and onto turntables nationwide.

”I liked his music right from the beginning,” remembers Volk, ”[my roommate] played the song and I swear when I heard that…husky and rough kind of half-talking and half-singing, I thought it was an old man. I thought it was an old wise sage, a guy with a white hair and a white beard who was like an old folk singer who was dug up and rediscovered. I didn’t know it was a young cocky kid.”

Two years later, Volk decided to drop out of college. The Raiders came calling and he joined them in February of 1965 at a gig in Las Vegas.

Upon joining the band, Volk was christened ”Fang” by Paul Revere. ”He said, Phil, you’ve gotta have a nickname. We all have nicknames — ”Smitty” and ”Mad Man Marcus” and ”Drake the Kid” and ”Uncle Paul”,’ he said. Look at those teeth. Let’s call you ”Bucky Beaver.” What do you think?’ and I said No, no, that’s not cool at all. I don’t like that.’ And he said How about ”Bugs”?’ and I said No, I respect Bugs Bunny too much to steal his name,’ and he said Well, you know, your teeth are like fangs,’ and he gave me an idea there.”

Upon joining the band, Volk was christened ”Fang” by Paul Revere. ”He said, Phil, you’ve gotta have a nickname. We all have nicknames — ”Smitty” and ”Mad Man Marcus” and ”Drake the Kid” and ”Uncle Paul”,’ he said. Look at those teeth. Let’s call you ”Bucky Beaver.” What do you think?’ and I said No, no, that’s not cool at all. I don’t like that.’ And he said How about ”Bugs”?’ and I said No, I respect Bugs Bunny too much to steal his name,’ and he said Well, you know, your teeth are like fangs,’ and he gave me an idea there.”

”Fang” quickly became a brand for Volk, one that he milked by using electrical tape to display the moniker on the back of his white Vox Phantom bass. At opportune times during performances, he would flip the instrument to reveal the backside.

”While Mark Lindsay was singing a very classy, romantic, glamorous song, I [would] flip my bass over behind him. He didn’t know this, and the camera follows me and I’m hopping back and forth like a jackrabbit and showing my teeth and baring that big grin which I became known for, and before you know it, we’re getting all this fan mail [saying] we want more Fang!’

”It became something that made interesting copy, interesting magazine covers, interesting stories, just talking about Fang.’ I know that Mark Lindsay doesn’t like this stat, but I had more magazine covers than he had,” Volk laughs.

Paul Revere and the Raiders were signed to Columbia Records and found themselves label-mates with the top acts of the day, including Bob Dylan and Barbra Streisand. According to Volk, the then-president of Columbia, Clive Davis, claims that in his first year as label head, Paul Revere and the Raiders outsold both Dylan and Streisand — combined.

Hallmarked by wild, almost vaudevillian stage antics, colonial costumes and choreographed dance moves, the Raiders might have been seen as purely a teen pop operation. However, in an industry where authenticity and musical prowess were constantly scrutinized by scholarly fans, the Raiders were particular about participating in every aspect of the recording process.

”Paul Revere, Mark Lindsay, Drake Levin, Michael Smitty’ Smith, and me, Phil Fang’ Volk, were the musicians,” Volk states. ”We were the guys who played our instruments and recorded the music in the recording studio with our producer, Terry Melcher, who was Doris Day’s son.

”The Raiders were leaders and innovators, we weren’t imitators. We had our own sound. We had our own place in the industry and we gained visibility because of being out there on the road all the time. We were the leaders in our genre. There were times that the Rolling Stones were our opening act. How many bands can say that?”

Another element that pushed the band’s popularity into the clouds was its constant visibility on television, thanks to Dick Clark’s dance show ”Where The Action Is.” America’s teenagers could feast their eyes on the revolutionary-themed musicians five times a week as the Raiders served as the show’s house band.

”That was one of the best launching pads for our singles because [they] could be heard and seen throughout the whole country on the same day,” says Volk. ”It was a great marketing tool and it really helped us and so our record sales really spiked.”

The band quickly and clearly became a force to be reckoned with, double-billing with the likes of the Rolling Stones and the Beach Boys.

”It was Raider-mania, it was Beach Boy-mania, it was Rolling Stone-mania,” Volk recalls. ”There were no other groups out there beside the Raiders, the Stones and the Beach Boys that were really breaking all the concert attendance records.”

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/ioufyn6j3cU" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

Life on the road in the 60s, according to Volk, ”was a beautiful village of musicians getting together and jamming and doing a lot of social things together and meeting each other or traveling together on the bus. And we went through some hairy, scary things together.”

Sometimes the ”scary things” were really scary.

It was commonplace for fans to toss items onto the stage during performances. Volk remembers the band encouraging fans to throw stuffed animals, which they’d in turn deliver to the local children’s hospitals. But one night after a concert, a hunting knife was discovered lodged into a cone of an amp. Apparently, it had been thrown with the barrage of paraphernalia from the audience.

”Someone was out to get us and someone could have hurt us real bad,” says Volk, ”but fortunately we got out without a scratch that time.”

Volk remembers all of the fabled pandemonium of the time, hysteria nowadays equated with Beatle-mania that followed the Raiders wherever they went. Fans chasing tour buses only to run right through plate glass windows and slam into telephone poles or cars. In Boston, a photo shoot to commemorate the band’s historic namesake went horribly awry when a mob of fans turned up.

”I ran up to the top of the stairs of the [Old North] church and Paul Revere ran inside the church and Mark Lindsay ran into the graveyard and was hopping over tombstones. I had this quick vision of everybody. Drake went inside a telephone booth and was trying to hold the doors shut and Smitty was running around. We were all separated and being torn apart. The police arrived with the riot squad with a paddy wagon and they gathered us all up and our outfits were completely torn to shreds.

”There were many times we had to run for our lives because when that mob crowd is following you, it could be dangerous.”

In 1967, at what was arguably the pinnacle of the group’s fame, Volk, Levin and Mike Smith decided to leave the Raiders and form Brotherhood. The decision came after the three became dissatisfied with their lack of compositional representation on the albums and the musical direction the band was taking.

”Mark Lindsay kind of wanted to stay with that teeny-bop thing with his own songs he was writing,” explains Volk, ”and we were writing songs with a lot more grit and a lot more edge and we thought the Raiders needed to stay a kickass rock band and not succumb to softer, lighter music because the era was getting very tough.”

Volk’s final performance as a Raider was the group’s only appearance on ”The Ed Sullivan Show,” almost exactly a decade after Elvis’ appearance inspired him to take up the guitar.

Unfortunately, the milestone was tainted with heartbreak. Volk had flown to New York from California directly after the funeral of his older brother George, who lost his life in Vietnam. The emotional rollercoaster left him torn up inside, rendering the drama that awaited him at the show that much harder to bear.

Drake Levin and Mike Smith flew with Volk to New York to perform on ”Sullivan,” but when they arrived, Revere gave the order that newly hired guitarist Freddy Weller would be performing in Levin’s place. More discord waited backstage, where an agent was attempting to convince Mark Lindsay to leave the band and embark on a solo career.

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/CJh3ga54hVc" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

”The situation at the Sullivan Show’ was very emotional because Paul was very angry we had left the group and that [this] was our last gig,” remembers Volk. ”There was so much happening, there was so much change, there was so much anger, there was so much emotion, there was so much pain. Anytime I see the clips, there are enough good shots there, but I can see in my eyes, I can see in the way I look, that I had gone through something pretty serious and pretty dark.”

Fortunately, Volk’s soon-to-be-bride, singer Tina Mason, was waiting for him back home. Mason was pregnant and although Volk concedes some initial fears about their future, says that as soon as he got off the plane from New York and spotted her waiting for him, he knew he’d left behind the Raiders for good and was ready to begin a new life. Almost forty-five years later, the pair is still together.

Over the span of only two years, Paul Revere and the Raiders racked up four top ten hits, three gold albums in 1966 alone, and an impressive 750 television appearances. In the northwest, both the Raiders’ and the Kingsmen’s cover of ”Louie, Louie” are regarded as the definitive versions. (The Raiders’ version hit #1 in the region and was poised to break nationally when Columbia’s A&R man Mitch Miller pulled the plug, simply because he didn’t like rock n roll.)

Considering the band’s many accomplishments, it baffles Volk why the Raiders don’t seem to garner the respect owed to them by music critics and key industry players.

Although the Raiders count longtime Rolling Stone writer David Fricke as a fan, Volk asserts that the band has often been devalued by the magazine. ”They’d rather write stories and deify people like Kurt Cobain, who was a drug addict, and a suicidal maniac. That seems to be their approach. We don’t measure up to their cool meter’.”

Case in point, he says, is the omission of any Raiders tunes from Rolling Stone’s top 500 songs of all time.

”Some of the songs they considered [to be] the greatest of all time were rap songs that had the f-word in the title, and I’m thinking you know what? That’s just going way overboard with trying to be so cool that you have to dredge up some of these vulgar, mean-spirited, nasty rap songs and call them great works of art.’ They’re poisoning the minds of a lot of young kids, they’re degrading women, they’re using vulgarity, they show a real great lack of respect for people in authority, and even the titles have words that the FCC won’t allow you to say on TV or radio. But yet they’re written up there as one of the greatest songs of all time to the demise and exclusion of let’s say, Faithfully’ by Journey or even Kicks,’ or Good Thing’ by the Raiders.”

Another achievement the band has yet to attain is induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, though there are several online campaigns via Facebook and otherwise to pressure the nominating committee to induct the band.

”I don’t think it’s the will of the fans or the people. I don’t think it’s really the expressed will of the fans,” Volk says regarding the denied induction. ”It baffles me. It’s a mystery that the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame has passed us over and that Rolling Stone magazine cannot say one kind word about us.

”It’s a big injustice that’s being perpetrated by the people who are in charge of [the hall of fame], and it’s unfortunate that they’ve turned a blind eye to our true history and the remarkable footprint that we left on the musical landscape back in the 60s. It’s unfortunate. I hope someday there will be justice.”

After leaving the Raiders, Volk’s Brotherhood released three albums, none of which were commercially successful, though they do hold a kind of cult interest. Currently, Volk is attempting to acquire the masters to reissue the albums with extended liner notes, additional photos and bonus tracks.

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/0pWcgzzZmgM" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

Through the 70s and 80s, Volk engaged in a number of musical projects, including a stint as bassist in Rick Nelson’s Stone Canyon Band which Volk calls a ”bittersweet experience.”

”We had philosophical differences,” he says, ”but I enjoyed the experience from a musical standpoint because I got to see [Nelson] rise back up out of the ashes and reinvent himself and have a new life as a rock star and a musician. I was there at the early stages of the reinvention of Ricky Nelson.”

Today, Volk is as involved in the music industry as ever. In addition to his forthcoming album (which contains ”Times,” along with a number of Dylan and Brotherhood covers), he is stepping out (no pun intended) into the limelight once again. On August 20 and 21, he will perform along with his wife Tina and daughters Jessica and Kelly in ”Phil Fang’ Volk, Family and Friends” at the Zucchini Festival in Hayward, California.

Although, Volk points out, the music business has changed over the years.

”[The music industry today] is not as nice, it’s not as friendly, it’s not as accommodating. There are not as many open-door policies anymore, there are a lot of closed-door policies. There’s a lot of emphasis on flesh, and on T&A, and it seems like all the girl singers have half their clothes off now when they’re doing their performances, like Rihanna and Lady Gaga and Ke$ha and Shakira.”

There are modern artists that Volk likes, particularly Ben Folds, the Black-Eyed Peas and Keith Urban, whose ”I Wanna Love Somebody Like You” is covered on his new album. But, it seems, for Volk, rap music is decidedly unlikable and, in fact, despicable. On his website, he calls the genre ”the downfall of rock n roll, the antithesis of romance and love,” a statement that he defends with passion.

”When I say it’s the antithesis of love and romance, it’s like the anti-Christ. Because God is love and Christ is all about love, but I don’t see that kind of love coming out of these rap lyrics.”

Instead, Volk prefers to create music that reflects where he is on his spiritual path as a Christian. His cover of ”Times,” from his perspective, fits the bill.

”[The song] has a good message and it reflects kind of the way I’m thinking,” he says. ”I kind of like to do things that match where I am spiritually in life. If I violate those spiritual principles, then I’m the one to be most pitied because whatever you do, you’ve got to do it for God’s glory.

”I’ve turned many corners in my life and had to readjust my thinking and reexamine who I am and where I’m going. You’ve gotta be true to yourself and true to your God and if anyone claims to be a spiritual man, then he also has to live it, right?”

”I’ve turned many corners in my life and had to readjust my thinking and reexamine who I am and where I’m going. You’ve gotta be true to yourself and true to your God and if anyone claims to be a spiritual man, then he also has to live it, right?”

When asked if he’d offer any advice to a younger version of himself, Volk responds almost immediately with ”say no to drugs.”

”If I have any regrets, I regret that I used drugs as much as I did and I took too many chances and I could have been killed. I didn’t need any mind-expanding drugs. I was so high on life. I always lived with passion and a lot of love for creativity and life.”

Does he regret other aspects of the rocker life? Well…

”Obviously life as a rock star on the road, you have a lot of sexual adventures because sex, drugs and rock n roll. That was the trifecta of the rock star,” Volk laughs.

”I can’t say I regret any of the girls that I met or any of the fun that we had. The excitement of the sexual revolution was in its prime and we hadn’t heard about AIDS yet. The only thing I might regret is could there be some other of my lineage out there that I don’t know about. There’s a lot of stuff that went on on the road and you don’t know what the final outcome was of all of that, you know.”

He says that later in life, both Drake Levin and former Raiders guitarist Keith Allison connected with children they had fathered unbeknownst to them.

Volk says he receives emails and Facebook messages from women he met on the road, but can’t always place them.

”We met so many people and we had so many girls…I don’t mean to make this sound cavalier or macho or anything but I’m just saying sometimes it breaks my heart a little that it was a very important moment for the other person, but I can’t necessarily remember it.

”If I’ve touched anybody’s lives or was intimate with anybody or shared some tender moments, I just wanna say thank you for getting close to me and making my life joyful for that moment and sharing some love together. What else can I say?”

Volk plans to pen an autobiography to expound on his memories as a Raider and tell the stories that he feels will help to not only commemorate, but validate, the band and its many achievements.

As for the other Raiders?

”Paul Revere and I are close,” he says. ”He gave me a big break by hiring me and bringing me into that band and allowing me to prove myself because at first I didn’t have all the bass chops. Mark [Lindsay] had suggested he’d get rid of me before I’d even had a chance to prove myself but Paul said no, let’s give him a little time. He’s going to be a great entertainer, you watch.’ And so Paul had faith in me and I owe him a big debt of gratitude.”

He is also close with Jim ”Harpo” Valley, who replaced Drake Levin when Levin served in the National Guard from 1966 until rejoining the band in time for the spring 1967 tour. Recently, Valley visited Las Vegas with Rainbow Planet, his musical workshop for children, and Volk helped him with equipment and support, and served as Valley’s ”go-to guy.” ”That’s the kind of friendship we have,” says Volk, ”and he would do the same for me.

”But unfortunately, I don’t get that from Mark [Lindsay]. I don’t get any of that love or sentimentality or any cooperation of two guys that shared so much together. It’s so sad that we can’t have some good moments together at this late a time in our life, you know?”

Despite attempts to reach out and embrace Lindsay in the spirit of brotherhood the two once shared, Lindsay seems to be uninterested.

”I haven’t done anything wrong to him. I never sued him. He and Paul Revere had a lawsuit, they hate each other. Paul will have nothing to do with Mark and so if we get inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and we all have to be on the same stage together, that’s gonna be pretty interesting!” Volk laughs. ”It could be volatile, it could be crazy, it could be rough, it could be awkward, there could be animosity, who knows? But I’ll be there because I don’t have enemies in the band.

”Nobody in Paul Revere and the Raiders is my enemy. I’m disappointed in Mark, but I’ll stand right next to him and sing and play with him because I think that’s what we owe each other. That’s what we owe each other.

”It took five guys to develop the fame and the legacy of the Raiders, not just one. It was a team, it was a Super Bowl team, and when a team wins the Super Bowl, they work as a team and they do it together and they share the fame together and that’s how I see the Raiders. And if Mark doesn’t see it that way, I’m sorry, but that’s the way I see it.”

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/jEUmcuMcgdQ" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

Sadly, Drake Levin died of cancer in 2009; Mike ”Smitty” Smith passed away in 2001.

The legacy of the Raiders is a continued issue of importance to Volk. ”We were a kickass, tight rock and roll band that played the dance circuit for a long, long time before we got to the studio. And by the time we got to the studio, we were ready to rock, we had our own chops, we had our instruments down, we had prepared for that moment.

”We were musicians first and entertainers second and it was all about the music. We were the guys who played the music on the records, and I wanna make sure that fact gets out.”

Even though the campaign for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame still seems like something of an uphill battle, Volk is optimistic about the perception of the Raiders turning for the good.

”People are starting to realize what a force we were in the industry back then. Ever since the Collector’s Choice CD [package of the Raiders’ hits] came out, all the writers are saying these guys deserve to be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, they did not get the credit they deserve and these guys were a force in the industry.’ It’s really nice finally to see the change and see that people are finally realizing that we were more than our costumes and dance steps. We were musicians first.”

Volk carries that spirit of musicianship into his more recent recordings, including ”Times.” He says his efforts are still directed toward staying true to his roots.

”I’m really putting my heart and soul into it. I’m not trying to be anything that I’m not, I’m just trying to be myself. My parents always told me just be yourself and that will be the most original thing you can come up with’.”

Related articles

- The Popdose Interview: Franke Previte (popdose.com)

- The Popdose Interview: Jeremy Fisher (popdose.com)

- Bob Dylan: The Poet At 70 (popdose.com)

- The Popdose Interview: Garland Jeffreys Returns from “In Between” (popdose.com)

Comments