When I became involved with Ted Nugent’s recording, I spent quite a bit of time in Atlanta. We were recording at The Sound Pit, a nice little studio in downtown Atlanta owned by a man named Mike Thevis, who apparently had something to do with pornography, and who also apparently spent some time in prison as a result. I never met Mr. Thevis, but I did become very friendly with the house engineer, Tony Reale. Tony was a great engineer with a very agreeable personality. Aside from engineering my early records with Ted, he also mixed the Johnny Nash hit “I Can See Clearly Now.” To a visitor like myself, Atlanta in the Seventies had the feeling of a boom town Á¢€” we were told that women outnumbered men three to one, and the population was young. There was a buzz about the town, and a festive atmosphere. Anyone who grew up in the South and had a dream seemed to be drawn to Atlanta in order to realize that dream.

When I became involved with Ted Nugent’s recording, I spent quite a bit of time in Atlanta. We were recording at The Sound Pit, a nice little studio in downtown Atlanta owned by a man named Mike Thevis, who apparently had something to do with pornography, and who also apparently spent some time in prison as a result. I never met Mr. Thevis, but I did become very friendly with the house engineer, Tony Reale. Tony was a great engineer with a very agreeable personality. Aside from engineering my early records with Ted, he also mixed the Johnny Nash hit “I Can See Clearly Now.” To a visitor like myself, Atlanta in the Seventies had the feeling of a boom town Á¢€” we were told that women outnumbered men three to one, and the population was young. There was a buzz about the town, and a festive atmosphere. Anyone who grew up in the South and had a dream seemed to be drawn to Atlanta in order to realize that dream.

The Omni Hotel complex was brand new at that time, and it became my home away from home. My room overlooked the indoor ice rink, and the restaurant on the ground floor (Mimi’s) served great food and was moderately priced (as, it seemed, was everything in Atlanta). The Omni complex also housed the Omni Center, which was the largest indoor sports facility in Atlanta, and which became the largest concert hall in town, as well. When Ted headlined the Omni just after the release of our second album, Free For All, it was the first time I heard “Cat Scratch Fever.” I called my boss in New York the next morning and announced that Ted had finally written a hit single. While CBS Records was having one of its winter mini-conventions in Atlanta, Gregg Geller and I went over to see a band that had been recommended to me. They were called Mother’s Finest, and they were appearing at another major venue in town at the time, Alex Cooley’s Electric Ballroom.

I think it’s fair to say that this band, about whom we knew nothing in advance, fairly incinerated the stage. Fronted by a tiny package of dynamite named Joyce Kennedy and her husband Glenn, this was basically a black hard rock band, years before the days of Living Colour. The bass player, Wizard, went on to play bass for Stevie Nicks. He was a tall, grinning man whose physical dominance made the bass guitar appear as a toy in his giant hands. He just slapped that instrument silly. The drummer and lead guitar player were white, but in this band, the music was really dark gray Á¢€” their main influence was Zeppelin, but with a very high funk quotient.

People in Atlanta loved them. Once again, while Gregg and I watched them in wonder, we found no other label A&R people in attendance. I signed them immediately, and made a first album titled Mother’s Finest with great songs, but with production that I considered something less than my best work. The arrangements were solid, but the sound didn’t do the band justice. By the second album, I had managed to dial the sound in a bit more accurately, and we turned out some real gems. We did a version of “Mickey’s Monkey” that should have been a hit. Back at Epic, the promotion and marketing people declared that they were having trouble at radio — that the records were too white for black radio and too black for white radio, and that the album “fell between the chairs.”

I highly recommend “Mickey’s Monkey” and “Truth’ll Set You Free” from this album, titled Another Mother Further. I was so happy to be doing something outside of what the industry considered my little white hard rock pigeon hole Á¢€” and so disappointed by the lack of success for the band. They remain a cult band to this day. Those who know them love them, but it’s too small a number. They were among the nicest people I ever worked with.

I highly recommend “Mickey’s Monkey” and “Truth’ll Set You Free” from this album, titled Another Mother Further. I was so happy to be doing something outside of what the industry considered my little white hard rock pigeon hole Á¢€” and so disappointed by the lack of success for the band. They remain a cult band to this day. Those who know them love them, but it’s too small a number. They were among the nicest people I ever worked with.

During the making of the second album, I became quite fond of a band I would see frequently after the sessions in an area of town called Buckhead. Over there, people had taken a neighborhood on the decline and converted houses to businesses and clubs. One of these clubs featured a band called Whiteface, who had a singer/bass player named Kyle Henderson. Kyle was tall, thin, handsome, and had a great voice. I would see them a couple of times a week, and the club owners would take care of me and my guests in a variety of ways. It was a superb way to unwind after a session, and when Whiteface morphed into a band calling itself the Producers, I felt they were the greatest thing since sliced bread Á¢€”or at least since the Police.

This was the perfect pop band Á¢€” spare, mod, with smart, catchy songs like “What’s He Got” and “She Sheila.” During the recording of the first album, I was positive that this would be the next big thing on pop radio, and that all we had to do was let people hear this band and then stand back. The keyboards had a unique style; the guitar was crisp and distinctive, as well. The songs were wonderful, the singing was great, and the drumming was right up there with Stewart Copeland. Yet the band had a true identity separate from the Police, who were an obvious influence.

Normally, I’m ready to take the blame for average records or production errors, but with the Producers, I have to say that much of the blame for their failure should go to Portrait Records, a newly formed Epic-associated label. Here was the most commercial stuff I had ever done Á¢€” hands down Á¢€” and the band remained a cult item. Their failure to break big was really what drove me to leave CBS. I recommend the entire first album, simply titled The Producers. The band’s failure to break was probably the biggest disappointment of my career.

The Producers were signed to Epic in 1981, and I mention them here because I was discussing Atlanta. But let’s go back to the mid-Seventies , when things were really starting to heat up at Epic Records. Epic’s association with Gamble & Huff’s Philadelphia International Records, which began in the early Seventies, was continuing to yield many hits in 1976, and that year also marked the signing of the Jackson Five to Epic. We had a staff lunch with the Jackson Family in one of the conference rooms, and we had a chance to meet and chat with all the brothers. I recall that they were very courteous, and generally soft-spoken, with the possible exception of the father, Joe Jackson, who seemed a little less affable, and less communicative. But the boys were enthusiastic. A few years later I ran into Michael again in Los Angeles during the recording of Thriller, and he was very soft-spoken and polite. I remember being surprised by how tall he appeared to be. Maybe it was the shoes?

Also in 1976, I received a phone call from a woman whose name I knew, and who wanted to talk to me about coming to work as my secretary (they were still called secretaries in the dark ages of the Seventies, and not yet “assistants”). While I didn’t readily understand why she would be seeking a job like this, it was indeed May Pang who came to meet with me in my office. For those who may not recognize the name, May was John Lennon’s girlfriend, and a close associate of20both John and Yoko. In 1976, John was probably among the top three names in music in the world, and May was intelligent, personable and articulate. I couldn’t believe my good fortune, since an association with her would give me social and professional access to the greatest names in rock music.

I submitted all the necessary corporate employment forms without hesitation, and waited for them to be processed. Imagine how I felt when CBS personnel called and informed me that May’s typing speed was too slow for her to be hired. I went down and spoke with the personnel department, and I tried to convince them that I cared not a whit about how quickly she could type, and urged them to consider the benefits that could result from this, but they read me the company line, and stuck to it. I couldn’t believe it, but I couldn’t really do anything about it, either. May and I are still friends through Facebook.

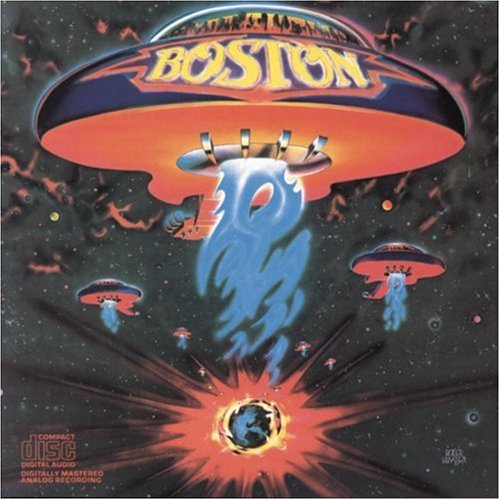

One day while the head of A&R, Steve Popovich, was away on a business trip, one of my colleagues, named Lennie Petze, came knocking on my office door, accompanied by a fellow he introduced to me as Paul Ahearn. Lennie explained that, like Lennie and myself, Paul came from Boston, and had brought a cassette of this new band he was working with. Lennie explained that he had heard it, and that he would like my opinion. We went next door to Steve’s office (bigger, more couches, better stereo) and I put the cassette in the player. I still can see the scene clearly in my mind’s eye, as the experience was so memorable. We listened to the first tune, which I would characterize as the best single song demo I’ve ever heard in my life, and then halfway through the second tune, which was every bit as good as the first, I leaned over and put the cassette player on pause.

I looked at them for some kind of explanation, and asked if perhaps this was actually some musical version of Candid Camera. I told them this was simply unbelievable music Á¢€” with a whole new guitar sound Á¢€” that sounded like it might have been made on another planet. Paul, the band’s manager, said he was gratified that both Lennie and I responded so positively to the music, since we were his last stop in New York, and that everyone else he had seen that day had passed on it. I had trouble believing this, but he swore that we were the only label who really liked Boston’s demo tape. The first song was “More Than a Feeling,” and I told Lennie and Paul to sit tight while I phoned Steve. I told Steve that I believed we had just discovered what was perhaps the best rock & roll band in the country, and asked if we could go see them live at the earliest possible moment. He responded with “Better than the Who, Werman?” because he knew this was my favorite band. I replied “I said Á¢€Ëœin the country’, Steve.” After the phone call, I turned to Paul and told him that if his band could even approach this demo in live performance, I guaranteed him a very generous album deal. Of course, I had no authority to promise this, but I thought it was the most effective way to express our enthusiasm for what we had heard.

I looked at them for some kind of explanation, and asked if perhaps this was actually some musical version of Candid Camera. I told them this was simply unbelievable music Á¢€” with a whole new guitar sound Á¢€” that sounded like it might have been made on another planet. Paul, the band’s manager, said he was gratified that both Lennie and I responded so positively to the music, since we were his last stop in New York, and that everyone else he had seen that day had passed on it. I had trouble believing this, but he swore that we were the only label who really liked Boston’s demo tape. The first song was “More Than a Feeling,” and I told Lennie and Paul to sit tight while I phoned Steve. I told Steve that I believed we had just discovered what was perhaps the best rock & roll band in the country, and asked if we could go see them live at the earliest possible moment. He responded with “Better than the Who, Werman?” because he knew this was my favorite band. I replied “I said Á¢€Ëœin the country’, Steve.” After the phone call, I turned to Paul and told him that if his band could even approach this demo in live performance, I guaranteed him a very generous album deal. Of course, I had no authority to promise this, but I thought it was the most effective way to express our enthusiasm for what we had heard.

A few days later, Lennie and I returned to Boston for Thanksgiving break, and we arranged to see Boston play live at Aerosmith’s rehearsal facility in a suburb of Boston. While the live presentation was a little stiff at that point, and while Tom Scholz was not exactly Pete Townshend on stage, they did indeed come very close to the recorded sound.

Things progressed, and the project ultimately was produced by John Boylan, new to the Epic staff on the West Coast. John was an experienced producer, although mostly with folk-rock (Linda Ronstadt, Rick Nelson, some of the early Eagles). I was a little inexperienced to be producing this new act, but John was an excellent choice, because Tom Scholz co-produced, and would have ridden right over anyone with less experience and knowledge. I well remember the night during the following July, when I listened to the finished album on headphones while gazing out over Los Angeles from a balcony on a high floor at the Century Plaza Hotel during our convention. It was a transporting experience.

In an earlier installment, I mentioned that I would cross paths again with Bruce Springsteen; at the 1972 London convention, Bruce and the band appeared at one of our dinner shows. Mike Appel had managed the band, and had produced the band’s first record. The convention show was particularly potent, and at the close of the show, while the audience was roaring its approval, I left my table and ran backstage to congratulate Bruce. Having initially been less than bowled over by this artist, I hadn’t been too impressed by the record either; but that night I was surprised and delighted by the strength of the live show. For some reason, I found him backstage standing apart from the band, and in my unbridled and blind enthusiasm, I blurted out what a fine show it had been, that he was truly great, and that his live performance was so far beyond his record (which had met with little commercial success) that I felt he should have a better producer in order for him to bring the quality and the impact of his recorded music up to the standards he set with his live show.

A week or so later back in New York, I got a message that Clive Davis would like to see me in his office. Not having a clue what this was about, I went down to see Clive, who told me that he had just had a call from Mike Appel. Mike told Clive that Bruce had come to him and reported that I went backstage at the convention after the show and urged Bruce to get a different producer. Mike was understandably pissed. I blanched, not believing that Bruce had put me on the hot seat like this by sharing my advice with Á¢€” yes Á¢€” his producer!

My father had always impressed upon me that I should “do the right thing” in all circumstances, and I have always tried to live by this rule. In this particularly horrifying case, though, I simply had to deny the story. I said I had gone backstage, but Bruce must have misunderstood me Á¢€” after all, Bruce wasn’t even my artist; why would I say such a thing to him? I couldn’t believe how recklessly I had behaved, and I couldn’t believe that Bruce had actually taken this information to Appel. I felt bad for Mike, and I learned a big lesson early in my career. I felt fortunate to have escaped with my job intact.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=429ca375-9449-496d-940d-b58901aa65d5)

Comments