Recently, I watched two movies back to back that presented stories that played against type — in vastly different ways. Jordan Peele’s ”Get Out” and the award winning ”Hidden Figures” aren’t even remotely related in terms of genre or even story, but they do share some similar themes in terms of power, control, and even violence. But most importantly, both are movies where black characters aren’t sacrificed in violent ways to further the plot.

There are many movies where a black character doesn’t die, but that was not always the case. More often than not a black character would be the one who gets killed around the third act in order for other characters (usually whites) to survive, escape, or prevail. While many moviegoers may have ignored this predictable plot device, some have not. In film after film, there seems to be a moment in the story (usually a point of intense conflict begging for a release) where, yes, the black character dies. Shot, stabbed, poisoned, hung, flung off a cliff…the list can go on and on, but the point is that blacks seemed to be the sacrificial lambs in the story. The effect normalizes seeing black bodies take one for the team — while reassuring moviegoers (many of whom are white) that characters who look like them will survive, sometimes thrive, but almost always prevail. Another consequence of this narrative expectation is that it not-so-subtly devalues the lives of black folks. If you go to the movies a lot and see people who look like you consistently die in predictable ways in film after film or TV show after TV show, it’s difficult to get past the notion that your life is unimportant. And when compounded with news story after news story of unarmed black men getting killed by police with impunity, it’s easy to see how one can become cynical of Hollywood doing anything different.

But something has changed…

When given the opportunity to tell stories that deviate from the standard form, we get movies that adhere to certain narrative conventions, but sometimes defy them as well. And so it goes with ”Get Out” and to a lesser extent with ”Hidden Figures.” With ”Get Out” Jordan Peele has, like Joss Whedon did in ”Buffy The Vampire Slayer,” turned horror movie conventions on its head. Not only is the main character a black man, but he’s successful in ways that don’t involve sports, music, drug dealing, or riding a capitalist success story as a businessman. Nope. The main character, Christopher (Daniel Kaluuya) is a successful photographer. He shoots powerful black and white images of symbols of white oppression against blacks (i.e., the police, angry dogs, and the like). It’s clear he’s talented and successful, but he’s humble about what he has achieved. Chris is also in a relationship with a white woman, Rose, (Allison Williams) who has invited him to meet her parents at their home for the weekend. Before and during the trip, Chris finds out that Rose has not told her parents he’s black, is subjected to an ID search by a cop after Rose hits a deer while driving, and arrives at the parent’s home, only to find that their gardener (Ma rcus Henderson as Walter) and maid (Betty Gabriel as Georgina) are both black — and unusually subservient in an almost a robotic way. Rose assures Chris that Walter and Georgina have worked for the family for a long time and her parents are boring, liberal, and — with regards to her father — ”would have voted for Obama for a third term if he could.” Still, Chris is concerned that even with their liberal bona fides, Rose’s parents might be surprised by who’s coming to dinner. Right from the start, however, it becomes increasingly transparent that Rose’s folks are putting up a front to something more sinister beneath their openness. Bradley Whitford and Catherine Keener (as Dean and Missy Armitage) pepper Chris with questions about his personal life in ways that seem like an interview. And Chris’s visit is an interview of sorts. He is under the microscope not because Rose’s parents want to get to know him better, but are sizing him up for grander plans.

rcus Henderson as Walter) and maid (Betty Gabriel as Georgina) are both black — and unusually subservient in an almost a robotic way. Rose assures Chris that Walter and Georgina have worked for the family for a long time and her parents are boring, liberal, and — with regards to her father — ”would have voted for Obama for a third term if he could.” Still, Chris is concerned that even with their liberal bona fides, Rose’s parents might be surprised by who’s coming to dinner. Right from the start, however, it becomes increasingly transparent that Rose’s folks are putting up a front to something more sinister beneath their openness. Bradley Whitford and Catherine Keener (as Dean and Missy Armitage) pepper Chris with questions about his personal life in ways that seem like an interview. And Chris’s visit is an interview of sorts. He is under the microscope not because Rose’s parents want to get to know him better, but are sizing him up for grander plans.

Without giving away too much of the plot, it becomes evident during Chris’s weekend stay that Dean, Missy, Rose, and even Rose’s creepy brother Jeremy (Caleb Landry Jones) are verbally and physically poking and prodding Chris’s weak spots to see how they can take advantage of those weaknesses and control him. It’s only when Missy (who is a psychologist) hypnotizes Chris to ostensibly cure him of his smoking habit, that her true motives become overt: his mind and body are being controlled for nefarious ends.

Throughout the movie, comments about Chris’s physicality, sexual prowess (”Is it true what they say?”), and artistic talent are being measured as commodities that are quite literally auctioned off to a group of older white people at a party Dean and Missy are hosting. From that point onward, ”Get Out” lapses into a more or less standard horror movie — but with a slight twist: the black guy does not die. Indeed, if there were ever a revenge fantasy movie for black folks, ”Get Out” is a contender. The standard tropes of the horror genre are fairly well known (if you need a refresher, just rewatch ”Scream”). However, Jordan Peele pulls a ”Buffy The Vampire Slayer” and makes a character who is usually a victim, the smart one who turns the tables on his captors. More than once during the third act I heard people in the audience applauding Chris’s actions. And more than once I heard audience members yelling ”Yeah!” as one tormentor after another lost the proverbial high ground and perished. The catharsis was evident in the clapping and yelling. It was like a collective voice screamed ”Finally! Finally, a movie where black bodies aren’t sacrificed so white characters can be saved.”

Over twenty years ago, cultural critic Henry Giroux wrote about the use of violence in cinema in the academic journal Social Identities where he identified symbolic violence as acts that connect ”the visceral and the reflective.” It’s not merely violence portrayed for spectacle or mental masturbation, nor is it hyperreal like ”Reservoir Dogs” or ”Natural Born Killers.” Rather, symbolic violence is used to shake up conventions and expectations that cause the audience to reflect on the contradictions depicted on the screen. That type of violence was evident in ”Get Out.” The audience reaction to the visceral images not only provoked audible commentary in the movie theater, but even celebrities like Kareem Abdul-Jabbar reflected in a piece he wrote for The Hollywood Reporter on the way in which ”Get Out” identifies how — like Martin Luther King did in his ”Letter from Birmingham Jail” — the white moderate allegiance to order over justice is a barrier to black freedom.

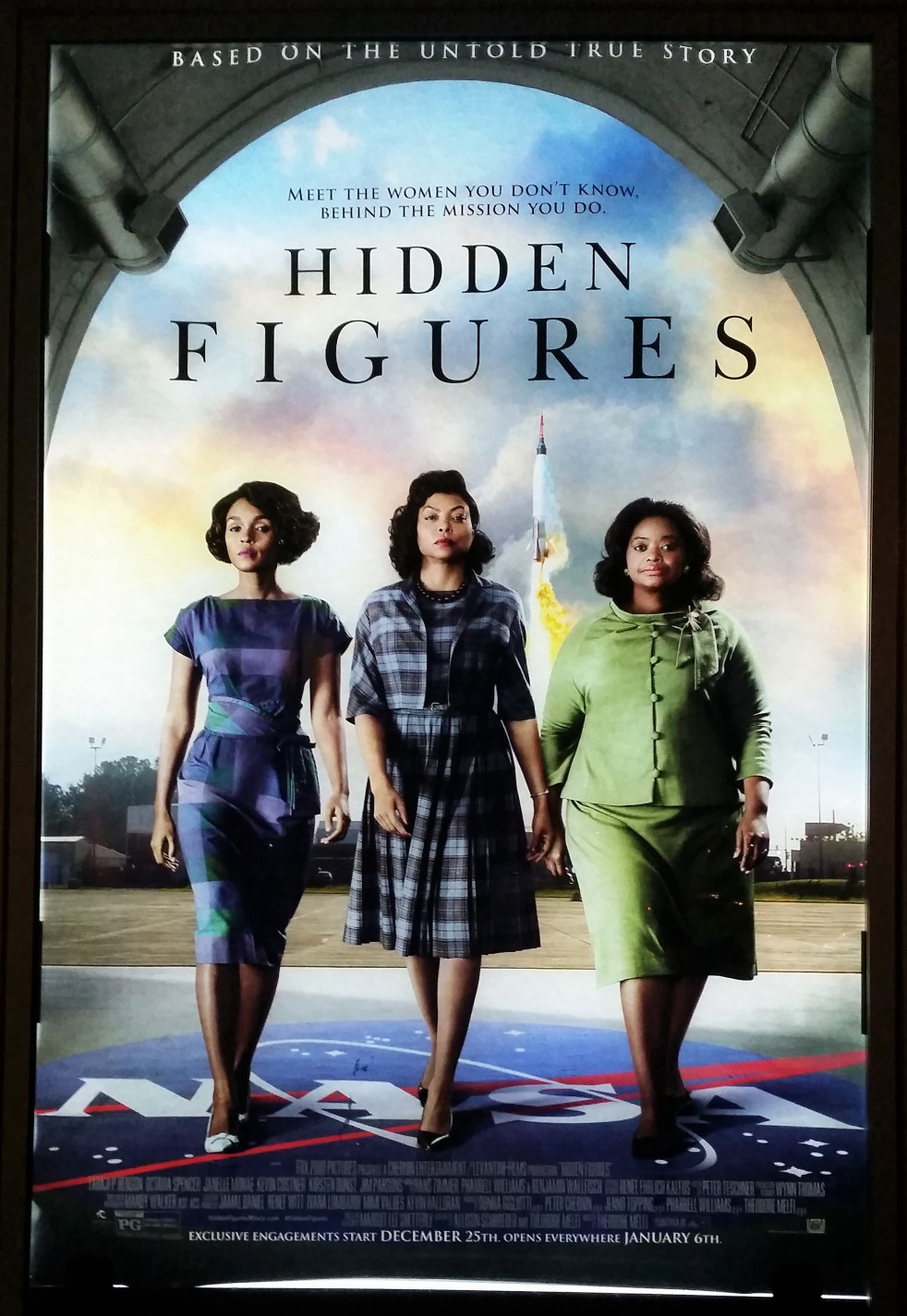

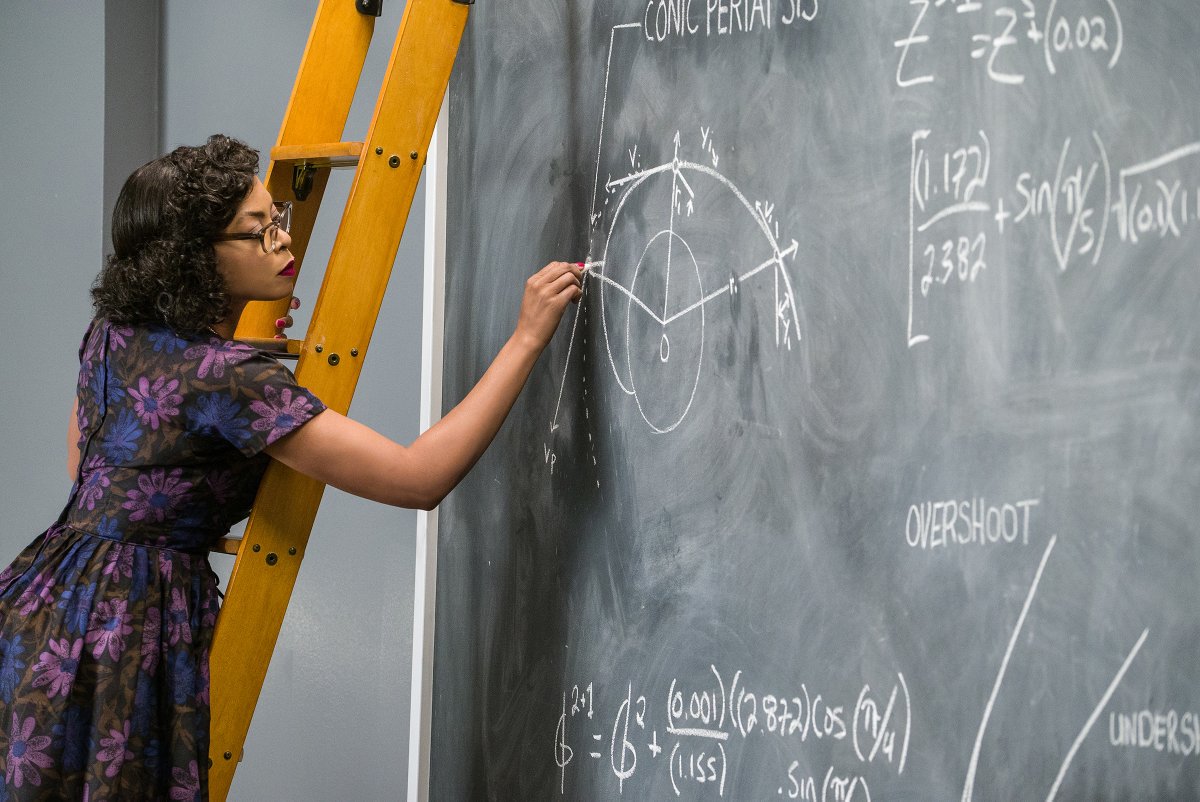

With ”Hidden Figures,” the setting isn’t a liberal enclave where science, power, and money intersect with a violent and vicious form of racism in the service of the highest bidder, but rather Virginia during segregation in 1961. Within the segregated South, three women who work for NASA as ”computers” (as in they do mathematical computations), struggle against the racist regime that kept blacks separate and unequal. NASA is not an organization that springs to mind when thinking about bastions of racism (after all, they are in the business of using science and technology to launch rockets into space), but in Virginia in the early 60s it was. ”Hidden Figures” stars Taraji Henson (as Katherine Goble), Octavia Spencer (as Dorothy Vaughan), and Janelle MonÁ¡e (as Mary Jackson), portraying black women who had important roles calculating mathematical variables for NASA’s Mercury missions. The work was tedious (something computers took over shortly before the launch of Friendship 7 that put John Glenn in orbit), but it was a job that paid the bills. The movie made sure we knew we were watching exceptional women on screen. Women who had intelligence, drive, and determination, and use their knowledge in ways that would advance them individually as black women and serve as an opening to advance blacks collectively. But we also see the repressive system they live in; a system where they are required to be subservient, grateful for white kindness, and often living in state of anxiety where violence against them could be unleashed at any moment. Against this backdrop of constant tension, the main story centers on Katherine Goble and her advancement to the Space Task Group. The Group is having difficulties getting rockets into space (they keep exploding), and they have enormous pressure on them from the Kennedy administration to get a man into space because the Soviet success in rocket technology poses a security threat to the U.S.

The Cold War, the space race, the Civil Rights Movement, and the realities of racism embedded in American culture intersect in ways that create an opening for Katherine and her peers to overcome barriers for black women in a white male dominated industry. And while ”Hidden Figures” adheres to a kind of bootstrapping can do-ism that makes for inspiring stories of how the long arc of history bends toward justice, it also highlights how the talents of blacks are used in the service of larger forces. In a way, Katherine, Dorothy, and Mary are being used by white society to maintain a global western white hegemony — while opening up individual avenues for incremental gains for the black women at NASA. We’re reminded in the film that the Soviet Union was a repressive regime with their own global ambitions, but so was the South for much of its history. And ”Hidden Figures” indicates that when racism becomes inconvenient to the forces of technological progress, some societal barriers come down — not because justice demands it, but because the space race does.

Nowhere is this more clear than when Kevin Costner’s character (Al Harrison as the Director of the Space Task Group) takes a crowbar to a sign that says ”Colored Women’s Restroom” and beats it down from the wall. ”At NASA, we all pee the same color” Harrison declares — which made for an unintentionally comedic moment. Harrison’s outburst was a reaction to Katherine’s trips to the colored restroom — which were a half mile away from her desk — and why she was missing from work for 40 minutes a few times a day. The point was clear, however. Segregation not only keeps blacks from achieving their full potential, but it cripples the larger society from succeeding as well. This point was made bluntly after Katherine had to explain to Harrison in front of her co-workers how far she had to go just to relieve herself, and how no one wanted her to drink from the same coffee pot as her (she had to make her own coffee in a pot labeled ”Colored Coffee.”). Despite Katherine’s speech which — as Andre Seewood labels a master assumption of a black story as ”We shall overcome — someday“ — was muted by a counterpoint to a master assumption of a white story: it takes a white man to end segregation. In other words, ”We (i.e., whites) shall always prevail.” Are narrative conventions like this woven into the film to soothe whites audience members who may become uncomfortable when prodded to reflect on the portrayal of black repression and white privilege and power? Is Al Harrison’’s ”We don’t have time for racism” attitude meant to create a zone of comfort for whites who also feel the same? It’s likely both master assumptions were woven into the story for a number of reasons, but it’s the master assumption of the black story that is front and center in the film.

Throughout the movie, we see how Katherine rises on her talents to become a trusted ”computer” who knows her numbers will bring John Glenn (who wants to prevail) back to earth safely. She is able to somewhat overcome the skepticism of her white, mostly male colleagues and prove that she’s not only capable, but exceptional at what she does. Dorothy also overcomes barriers placed in front of her regarding her lack of understanding of Fortran — the computer language that runs NASA’s IBM computer that will also render Dorothy’s job redundant. She has to battle white panic when looking for an introduction to Fortran in the white section of her public library — because the colored section of the library doesn’t have books on computer languages. She knows that if she doesn’t learn (and master) Fortran, she’s out of a job — so she steals the book. When her child protests what’s she’s done, she justifies it by saying that her taxes helped pay for that book, and if it was in the colored section, she wouldn’t have to steal it. Mary’s ”We shall overcome — someday” moment comes when has to convince a white judge to let her enroll in an all white school so she can take classes for her engineering degree. She gives an impassioned speech about people who are the first in their family to achieve something. She reminds the judge that he was the first in his family to go to college, earn a law degree, and eventually get appointed as a judge. Her argument wins her a seat at the school she needs for her degree — but the judge throws a slight wrench into her ambitions by saying she can only attend night classes.

People want to see characters succeed (or resolve conflicts) when they go to the movies. Making sure we sympathize and root for the protagonists isn’t anything new. However, an assumption about white acceptance or rejection of racism in ”Hidden Figures” comes from Harrison’s success in changing the culture of NASA to be more accepting of black workers — mostly because the fate of the western world rests on us as Americans to prevail against the Soviets. His fight could have easily gone the other way. That is to say, when black women (and blacks in general) cease to be useful in the white narrative assumption of ”We shall always prevail,” embracing (even begrudgingly) the racial power structure to maintain white power and privilege becomes paramount to their economic and social survival. We see this in how black talents are pillaged by white society to maintain their power in both films; how black minds and even their bodies are used to further the ”We shall always prevail” narrative of whites. While Jordan Peele makes this point quite bluntly in ”Get Out,” and Theodore Melfi has it simmering on a low boil in ”Hidden Figures,” it’s clear Peele and Melfi highlight when black talent threatens white power structures, forces will align to co-opt, steal, or imprison those talents to control or destroy them. That’s a powerful narrative in an industry that has for decades conditioned audiences to accept that some lives are worth saving so they can prevail, while others don’t seem to matter at all.

Comments