Maybe someone more in tune with themselves than I am can find some kind of hidden meaning in Archaia’s Tale of Sand, an adaptation of an unproduced screenplay by Jim Henson and Jerry Juhl. After writing a couple of drafts of Tale of Sand in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the ambitious project was eventually abandoned as the duo discovered that their future was in characters like Big Bird, Kermit the Frog and Fozzy Bear. With those childrens’ characters, Henson was able to indulge his own sense of whimsy while constructing stories and situations that were able to be universally recognized and enjoyed by children as well as adults. Tale of Sand easily shows Henson and Juhl’s love for the absurd and fantastic but it also shows two writers who are more wrapped up in their many ideas rather than in trying to flesh out those ideas together into a meaningful story.

Maybe someone more in tune with themselves than I am can find some kind of hidden meaning in Archaia’s Tale of Sand, an adaptation of an unproduced screenplay by Jim Henson and Jerry Juhl. After writing a couple of drafts of Tale of Sand in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the ambitious project was eventually abandoned as the duo discovered that their future was in characters like Big Bird, Kermit the Frog and Fozzy Bear. With those childrens’ characters, Henson was able to indulge his own sense of whimsy while constructing stories and situations that were able to be universally recognized and enjoyed by children as well as adults. Tale of Sand easily shows Henson and Juhl’s love for the absurd and fantastic but it also shows two writers who are more wrapped up in their many ideas rather than in trying to flesh out those ideas together into a meaningful story.

A man named Mac finds himself in the middle of a celebration in a desert town. Everyone’s ecstatic to see him. The men clap him on the back and the women dance with him. It’s a grand time until the men hoist Mac up on their shoulders and carry him down the main street to cheers and shouts. Taking him down to the sheriff’s shack, he’s caught up in the excitement even if he does not know why. The sherrif just as warmly welcomes Mac, giving him a knapsack of supplies, a big key and a map. He tells Mac to start running when he crosses the line. And the last instruction or advice for Mac? Don’t trust the map.

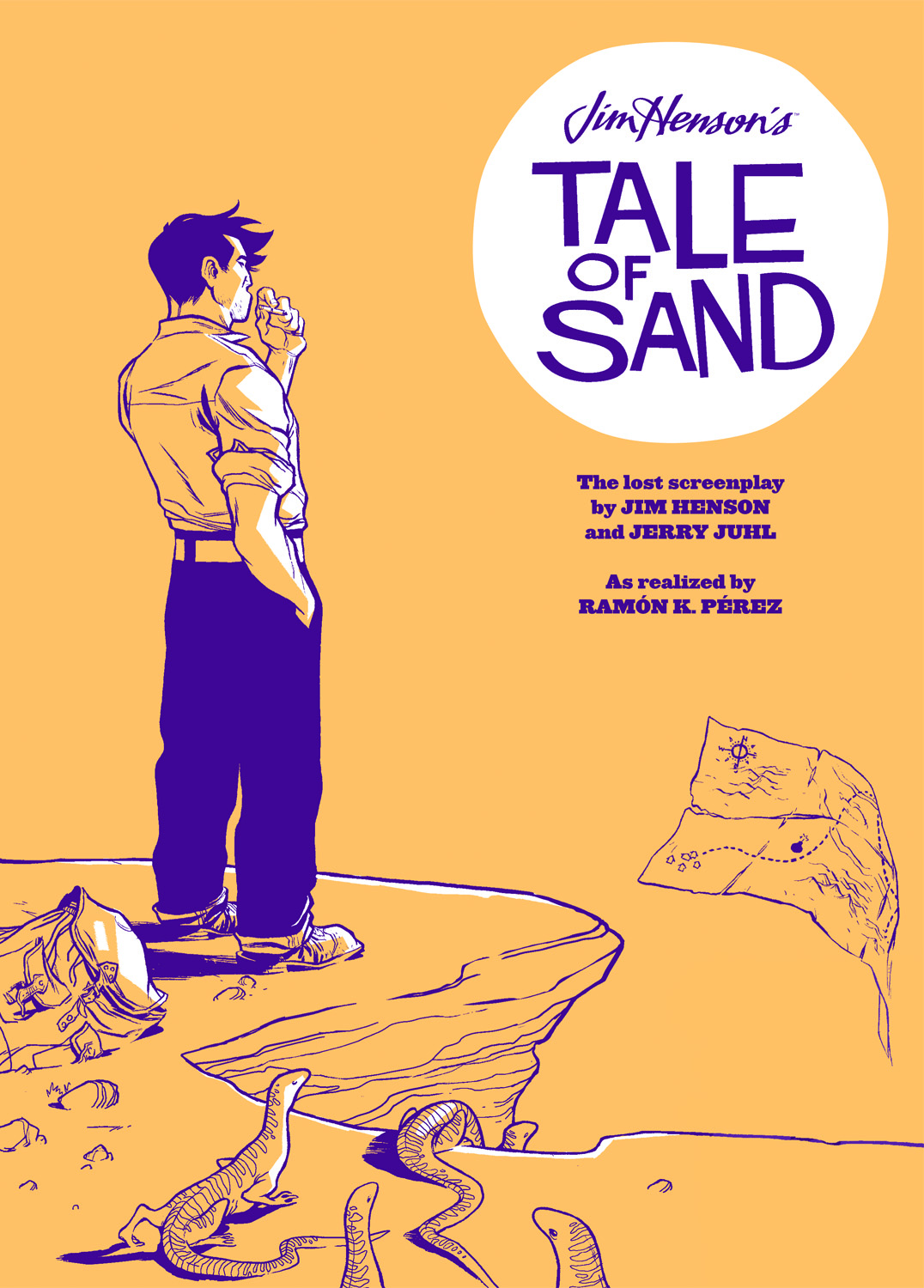

Adapting Henson and Juhl’s screenplay, RamÁ³n K. PÁ©rez embraces the non-sensical parts of Henson and Juhl’s story. And that’s most of it as the screenwriters embraced a stream-of-consciousness approach to show one man’s journey/race/chase across the American desert for a goal that’s never made known to him. He’s shown the start line, given a map and then told not to trust the map. From there, Mac’s journey takes him past lions, tanks, vitrolas, Arabesque tents, killing machines, old west towns, a devilish and sharp dressed man who also sports an eyepatch and a beautiful woman who pops up from time to time. Mac stumbles from one outrageous situation to the next in Tales of Sand, trapped in a journey that he knows nothing about and just looking for someone with a match to light his cigarette.

Henson and Juhl’s story is all about being clever and mysterious but it never does anything to feel real for the reader. The story is about seems to be about the meaninglessness of our actions but thanks to a largely silent leading man, Henson and Juhl never get to express this. They take the idea of ”show, don’t tell” to an extreme by hardly having any dialogue for their characters. This avoids a lead character reciting the plot to the reader or having the villain fall into the trap of point-by-point explaining his diabolical plot but it also doesn’t give the reader any way to know these characters on anything more than a surface level. The journey of the book is ultimately empty because we don’t get any insight into the personal journey of any of the players in this story.

PÁ©rez finds the life in an otherwise incomprehensible story. While the characters offer little in this story, PÁ©rez bends reality, time and his pages to create a whirlwind of action that makes you forget just how little characterization there actually is in this book. His artwork captures the futility of the story, making it into a Road Runner cartoon where Wile E. Coyote is both the hero and the villain. PÁ©rez conveys the absurd and the slapstick of the story, building these pages that flow beautifully but bombard you with images and ideas. He layers his pages with moments and images from the story that constantly build upon themselves, re-enforcing the chaotic nature of Mac’s adventures across the desert.

Adding to the desert locations, the colors create a shimmering, mirage-like feel to this book. PÁ©rez and colorist Ian Herring bathe the book in washed-out pastels, which help make this book feel like a dream that you can’t wake up from. From soft and luxurious oranges and yellows to harsh purples and reds, PÁ©rez and Herring’s color palette adds emotional punch to the images. They create a visceral bang that propels Mac ever farther and farther into the story and into more action and colors.

Looking at PÁ©rez’s images, it’s tough to figure out what Tale of Sand would ever have looked like as a live action movie. Captured on film, the story would have been too solid and too literal. Because of the use of real actors and real locations, the story would have felt too real. PÁ©rez makes the action and movements of the artwork the centerpiece of the book, allowing himself to blend images, styles and colors together in completely contrasting ways that gives Henson and Juhl’s story room to move in an abstract ways. The ways that the story is told makes up for the lack of a satisfying narrative as PÁ©rez gets caught up in the absurdity of everything, allowing his imagination and his pen to run wild.

Tale of Sand is both exciting and unsatisfying. PÁ©rez brings the pantomime alive but that’s all Henson and Juhl’s story is; a pantomine trying show off how deep and meaningful it is. PÁ©rez takes a rocky screenplay and makes it a visual feast, drawing pages that are stunning to look at, easy to read but difficult to figure out how they fit together into a story that Henson and Juhl wanted to make. Tale of Sand feels like a roadmap into Henson and Juhl’s mindscapes during the 1960s. But take the books’s advice and don’t trust the map.

Comments