There is at times a nobility in failed attempts, and something can be misguided and altogether unwise, but can still be okay. Take for example Peter Hyams’ attempt to continue the story of Heywood Floyd, former Chairman of the National Council of Astronautics. After the debacle with Discovery, the apparent murder of two astronauts rendered awake and an entire crew in their cryosleep chambers, he was kicked out and he subsequently became a professor at the University of Hawaii. He met a hot marine biologist and had a son, Chris. Most of this subtext is not rendered in 2010, The Year We Make Contact, the sequel to the much-lionized science fiction film from the late-1960s, nor does it really need to be.

There is at times a nobility in failed attempts, and something can be misguided and altogether unwise, but can still be okay. Take for example Peter Hyams’ attempt to continue the story of Heywood Floyd, former Chairman of the National Council of Astronautics. After the debacle with Discovery, the apparent murder of two astronauts rendered awake and an entire crew in their cryosleep chambers, he was kicked out and he subsequently became a professor at the University of Hawaii. He met a hot marine biologist and had a son, Chris. Most of this subtext is not rendered in 2010, The Year We Make Contact, the sequel to the much-lionized science fiction film from the late-1960s, nor does it really need to be.

I am of the mind that movies do an awful lot of overexplaining, as if the viewer can’t possibly enjoy a movie if they have to keep putting two-and-two together throughout it. I didn’t need all that stuff to guide me from 2001 and 2010, especially when the last quarter of the first film was so surreal that explanations were almost impossible already. What I did need were some points of clarification that guided me from movie one to movie two. For instance, Floyd (as played by William Sylvester in the first film) speaks from the Earth-orbiting transit hub via tele-phone to his daughter, a young girl with a clearly recognizable British accent. This is to be expected as expatriate director Stanley Kubrick preferred the security of his own means and, therefore, just cast whoever he wanted to cast as Floyd’s daughter. Regardless, this sets up expectations in the mind of the viewer that the daughter and probably her mom are of English extraction.

So what happened to them? Who knows; there is no mention of them in the film, and where all the other exposition was easily set aside, this in my mind is not. I can accept that Floyd is now played by Roy Scheider, but I had a hard time processing how Floyd’s British wife and daughter turned into his Californian wife and son. I’m sure this is explained in the books somehow.

Things not so easily explained are why Kubrick’s attention to the physics of space travel and such are disregarded. I know, I know, a lot of that is because Star Wars glorified the “hot rods in space” model of what space should be like with, you know, atmosphere. 2001‘s space was cold, silent and very scary in its emptiness. People had to wear special gear to stand upright and not float away like pens did with frequency. In 2010, things are zipping around and crashing and making all manner of sonic ruckus in space. People are walking around very casually, unaided by costume-means suggesting weights or velcro grips or anything else holding them in place. The Russian ship which Floyd is hitching a ride upon does have a centrifugal apparatus that, the viewer assumes, is creating a gravitational effect, but in times when it is most convenient (but not particularly logical) stuff goes flying around or standing in mid-air, etc. It is a form of physics that applies strictly to what the scene requires, cohesion be damned.

And yet I do get sucked into this movie when it is on. Scheider always did make such a great “everyman” and was certainly more charismatic than the stiff Sylvester. (That’s fine, as that was pretty much Kubrick’s way, wasn’t it, not only in this but in many of his movies.) As a kid that grew up through the tail end of the Cold War the allegorical nature of the film, that there are forces far beyond us that are going to force our evolution whether we like it or not, and our political differences mean nothing to them, always gets me in a specific way. That realization that we’re going to work together or we’re going to be left out is hard to turn away from. I’m actually even more enthralled by it now with the U.S. political system in such a shamble. We don’t fight the Commies anymore. We fight each other and call each other Commies. And something may be out there preparing to drag us to the universal negotiations table and they don’t really give a crap about birth certificates.

This isn’t about Martians (or in the case of 2010‘s narrative, Europans) but of things we are already facing. In 2012 we’re experiencing some of the wildest, most prolonged and severe weather that’s been on-record. Humanity may be confronted by a crisis that does not allow us to split off into factions to spar against each other.

If you are able to remove the thick shadow 2001 cast over film and film-making, and just accept the very linear and very standard nature of 2010‘s storytelling, it has the ability to stick with you. Writer/producer/director/cinematographer Hyams obviously cared a lot about this project. His other movies often had science-fiction themes: the moon landing conspiracy flick Capricorn One, the High Noon in Space of Outland, just to name two. He also had action credentials (Running Scared with Billy Crystal and Gregory Hines, which came out after 2010), but Hyams was always first and foremost a populist moviemaker that made for the audience; the largest he could get. Kubrick seemed to make movies for himself first and the audience thereafter. That’s a good thing because it helps foster auteurist films like 2001, but they hardly stand as popcorn-muncher entertainments. In tackling 2010, Hyams sought to pay homage to one of his biggest influences in film, yet his goals as a filmmaker were diametrically opposed to Kubrick’s goals and detachment, and even so, 2010 is pretty entertaining.

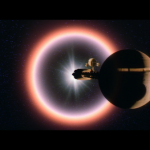

Dated, but entertaining. The film managed to get one catchphrase into the pop culture lexicon, so even though the film’s box office numbers were never staggering, and the dreams of franchise opportunities were abruptly deferred, it gave us “My God, it’s full of stars.”

Dated, but entertaining. The film managed to get one catchphrase into the pop culture lexicon, so even though the film’s box office numbers were never staggering, and the dreams of franchise opportunities were abruptly deferred, it gave us “My God, it’s full of stars.”

It also gave us a story with an optimistic premise, that we are not alone in the universe and that isn’t a bad thing provided we show a little respect. Actually we may be getting less lonely by the century, and one day the people of Earth might be able to be friends with our interstellar neighbors. It is a sentiment that flourished in the mid-to-late-1970s/early 1980s, and was typified by Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. As a society, and one fearful of “the other” at that, we don’t really hear or tell many stories of the strange-faced stranger that could be our friend. Even Spielberg has walked back from that vantage point of open-heartedness. Witness the past decade of his productions, including War of the Worlds, and you see again and again a distrust and reason to be scared of that which is foreign to us. He is not alone in this reappraisal, especially in a Hollywood atmosphere trying to tell 9-11-styled storied in a post-9-11 world. Fantasy and science fiction have taken that turn toward revenge rather than understanding.

So the medium actually devolved in that way. The science fiction movies from the Fifties and Sixties were notoriously fraught with the fear of strange invaders, body snatchers, and weird science gone too far. These were often allegories of the “Red Scare” of the concerns that Communism was infiltrating the American way of life, and so we must always be on the alert for “the other” and be prepared to strike it down at all costs. Movies from 1998 onward seem to have a common theme about them now: everything is out to get you.

So in that way, 2010 is one of the last serious times where a film attempted to present a universe as anything other than a battlefield or a haunted house full of creatures that mean us harm. While it could never match the film that preceded it, as an entertainment it works on it’s own level. One could do far worse with two hours than sit down with 2010: The Year We Make Contact. It is dated. The effects, impressive in their day, have not stood the test of time as well as its predecessor’s, but it is a story that can rope you in if you let it. It also suggests that, no matter what brink of devastation we seem to on the edge of this week, something else may be coming…something wonderful. Don’t screw it up, Earthlings.

2010: The Year We Make Contact ![]() is available from Amazon.com.

is available from Amazon.com.

Comments