We’re well into Movember now, the month-long event wherein thousands of men worldwide grow mustaches to raise awareness of men’s health issues. Count your humble Old Professor among that number. I usually keep a trim beard, but every November 1st I scrape my big dopey mug down to a shiny pink, and with the canvas thus made blank, I start workin’ on a sweet Fu Manchu.

We’re well into Movember now, the month-long event wherein thousands of men worldwide grow mustaches to raise awareness of men’s health issues. Count your humble Old Professor among that number. I usually keep a trim beard, but every November 1st I scrape my big dopey mug down to a shiny pink, and with the canvas thus made blank, I start workin’ on a sweet Fu Manchu.

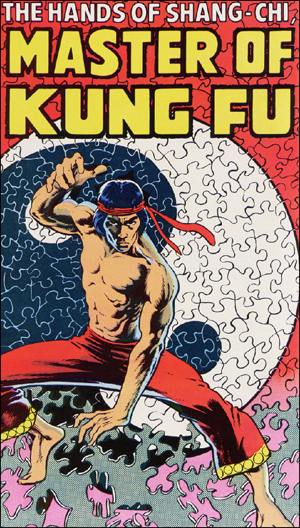

I first encountered this ornamentation — the King of All Staches, and as far as I know still the only one to be named for a fictional character — on the face of the eponymous Devil Doctor himself, in the pages of a Marvel comic called Master of Kung Fu. Not a title to inspire confidence, I know; it seems to promise the newsprint equivalent of the shoddy chopsockey programmers that lit up many a 70s grindhouse. But among the cognoscenti, MoKF — which made its debut in 1973, forty years ago this month — is legendary. At its peak, the book delivered high adventure with unabashedly arty leanings, a pan-stylistic mishmosh of Eastern philosophy, pulp thrills, and Bond-style spy-fi. Romantic, self-aware, and wildly ambitious, Master of Kung Fu was a game-changer, delivering on the vast potential of what the comics medium can be. It was about as good as mainstream funnybooks get.

But don’t bother to go looking for it, because you won’t find it. Though it was one of the first mainstream comics to be deliberately conceived and executed in long story arcs, perfectly suited for collection, you can’t buy it in paperback. No part of Master of Kung Fu’s classic ten-year run has ever been reprinted. Unless you’ve got the original issues, you’re out of luck. And it’s all because of that criminal genius, Dr. Fu Manchu.

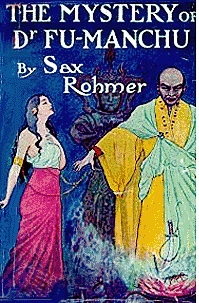

Before Master of Kung Fu — one hundred years ago, in fact, in 1913 — a trashy pulp novel called The Mystery of Dr. Fu Manchu became an unexpected bestseller on both sides of the Atlantic. In Mystery, the English writer Arthur Sarsfield Ward (using the pen name Sax Rohmer) created the character who would introduce a new archetype to popular fiction: the world-conquering criminal mastermind.

Fu Manchu’s background is kept intentionally mysterious. It is intimated that he is ancient, possibly even immortal, and that his unnatural lifespan entails unspeakable practices. A scientific genius, he holds doctorates from four Western universities. In the first book, he appears to be a simple crime boss, controlling the drug and prostitution trade in Limehouse, London’s Chinatown. That would be bad enough. But it is revealed that the Devil Doctor is using the profits from his criminal enterprises to fund a cult of assassins targeting Western imperialist leaders, and his true objective is nothing other than — dun dun DUN! — world domination, to be accomplished by scientific means more akin to sorcery; germ warfare, poisons, mutated scorpions. In all this, he is opposed by the doughty colonialist hero Denis Nayland Smith, with whom he shares a grudging mutual respect.

Fu Manchu’s background is kept intentionally mysterious. It is intimated that he is ancient, possibly even immortal, and that his unnatural lifespan entails unspeakable practices. A scientific genius, he holds doctorates from four Western universities. In the first book, he appears to be a simple crime boss, controlling the drug and prostitution trade in Limehouse, London’s Chinatown. That would be bad enough. But it is revealed that the Devil Doctor is using the profits from his criminal enterprises to fund a cult of assassins targeting Western imperialist leaders, and his true objective is nothing other than — dun dun DUN! — world domination, to be accomplished by scientific means more akin to sorcery; germ warfare, poisons, mutated scorpions. In all this, he is opposed by the doughty colonialist hero Denis Nayland Smith, with whom he shares a grudging mutual respect.

None of this was precisely new. There’s more than a little of Professor Moriarty in the Doctor’s makeup, and the honorable-adversary relationship between Fu and Smith cannot help recall that between the Great Detective and his nemesis. (Smith even has a sidekick, Dr. Petrie, who narrates his adventures.) Nor was Fu Manchu popular fiction’s first would-be conqueror of Asian extraction. That dubious honor one goes to one Kiang Ho, a Harvard-educated warlord who featured in an 1892 ”scientific romance” called Tom Edison Jr.’s Electric Sea Spider, or, The Wizard of the Submarine World, which I mention here primarily for its irresistible title. For Kiang Ho, you see, was just a warm-up act for Dr. Yen How, from M.P. Shiel’s The Yellow Danger, a hysterical racist screed from 1898; a half-Chinese / half-Japanese military strategist, Yen How unites the two countries and unleashes all the limitless hordes of Asia upon the unsuspecting West.

It’s easy to trace the cultural threads that gave rise to this xenophobic garbage. Large-scale immigration of Chinese to Britain and the US began in the mid-19th Century, and these new immigrants proved difficult to assimilate. Indeed, they seemed to show little interest in doing so, settling in ethnic enclaves where they remained culturally and linguistically isolated. Mutual incomprehension led to suspicion: Who could know what they were saying, in that gibberish of theirs? Who could know what went on after dark on those streets?

Around the same time, with the British Empire already in slow decline, Whitey was running the numbers and realizing to his dismay that the good times could not last — that his kind could not forever remain undisputed masters of the world. He may have had the guns and the money, but the mathematics were against him; Whitey began to realize that he was a minority population, and as the realization sank in, he went into a freak-out that continues, in some circles, to this very day.

But if Fu Manchu was not the first fictional villain to embody these simmering racial anxieties, it was in him that all the storytelling possibilities came together. The character became wildly popular, and remarkably durable. Rohmer wrote about Fu Manchu off and on until 1959, and he appeared in many films; but his true legacy is in the many, many subsequent villains of fiction to be modelled — in whole or in part, consciously or not — on the Devil Doctor of Limehouse. There were legions of outright knock-offs, most of them lost now to obscurity, and deservedly so. But some were as memorable as the good doctor himself. Flash Gordon’s Ming the Merciless, Marvel baddies the Mandarin and the Yellow Claw, The Shadow’s Shiwan Khan, James Bond’s enemy Doctor No — all straight-up homages to Fu Manchu. But elements of the character show up even where the ethnic signifiers are absent, in the likes of Doctor Doom, or in the Batman’s immortal arch-enemy Ra’s al-Ghul, even in Star Trek’s Khan.

So it was this Original Gangster cachet that Marvel Comics was counting on when the company optioned the rights to Rohmer’s characters in 1972. Comics publishing, like any commercial entertainment venture, is always scanning the horizon for a bandwagon onto which it can jump — and in the 1970s, that meant nostalgia. There was a positive craze for old-timey adventure, and publishers rushed to satisfy it, reviving their own catalogs of World War II-era heroes even as they snapped up the licensing rights for the pulp and paperback heroes of an earlier day, big names (e.g., Conan the Barbarian) and relative obscurities alike.

So it was this Original Gangster cachet that Marvel Comics was counting on when the company optioned the rights to Rohmer’s characters in 1972. Comics publishing, like any commercial entertainment venture, is always scanning the horizon for a bandwagon onto which it can jump — and in the 1970s, that meant nostalgia. There was a positive craze for old-timey adventure, and publishers rushed to satisfy it, reviving their own catalogs of World War II-era heroes even as they snapped up the licensing rights for the pulp and paperback heroes of an earlier day, big names (e.g., Conan the Barbarian) and relative obscurities alike.

Fu Manchu was certainly one of the big names, but — for a number of reasons — presented a problematic figure around which to build a franchise. Foremost of these was the inherent storytelling problem of having a baddie as the name above the title. The powers at Marvel decided early on to use Fu Manchu in an antagonistic role, and to build a book around around a protagonist opposing him. Not Nayland Smith — who to be frank was never a particularly interesting character — but someone new, and modern; someone without the baggage of Smith or Petrie, through whom a new audience could find an entry point for a sixty-year old franchise.

Now here’s where things get weird.

As mentioned above, there was a martial arts vogue sweeping the nation concurrent with the nostalgia boom. Along with the Fu Manchu license, Marvel held an option on the TV show Kung Fu, the genre-mashing chopsockey Western starring David Carradine. Tasked with creating a vehicle for Fu Manchu, writer Steve Englehart and artist Jim Starlin essentially combined the two properties, bringing the contemplative tone of Kung Fu into Rohmer’s lurid pulp world. They chose for their protagonist a naÁ¯ve young man, raised in a monastic setting, now adrift in a Western world that he little understands. Like Kwai Chang Caine, he possesses remarkable fighting skills, but seeks only to live in peace; yet he is continually drawn into conflicts not of his choosing — conflicts, in this case, with the forces of Fu Manchu. And just to give the conflict a personal stake, the protagonist is, in fact, Fu Manchu’s own son.

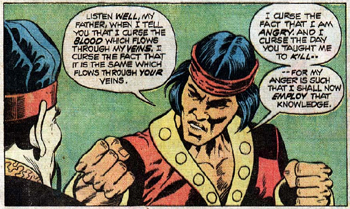

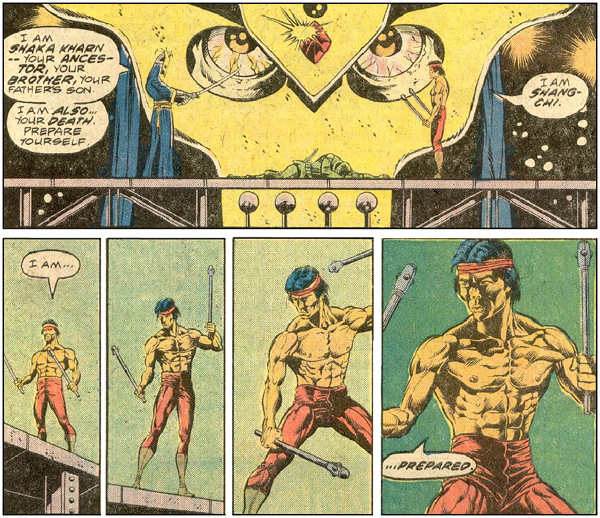

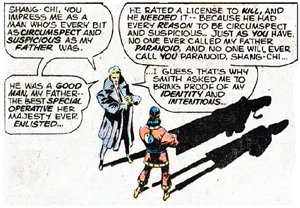

Master of Kung Fu is the story of Shang-Chi — a name which means ”the rising and advancing of a spirit” — raised by his nefarious father in the isolation of a fortress compound, where no Western influence could penetrate. Shang-Chi’s upbringing is a perverse experiment in using innocence as a tool of evil. He is raised with a reverence and respect for all life, and grows into a youth of near-superhuman martial prowess and impeccable moral character. But he has been lied to, since birth — taught to idolize his father as a paragon of all that is good and righteous. When Shang-Chi comes of age, Fu Manchu orders him to travel to London, and to kill his father’s enemy, Dr. Petrie. Shang-Chi, believing Petrie to be evil, willingly undertakes the mission, and heads off into the big world for the first time, like Candide recast as an assassin. But Nayland Smith intervenes and confronts Shang-Chi with evidence of his father’s villainous career. Realizing the monstrous deception that has deformed his entire life, Shang-Chi rebels against Fu Manchu.

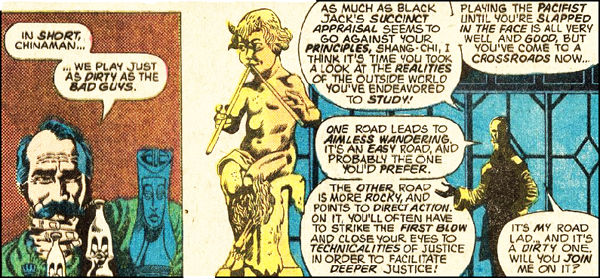

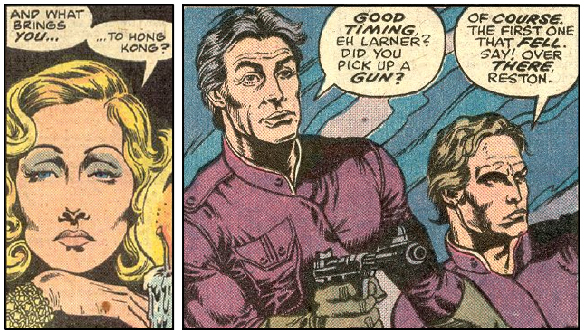

Even with its premise in place, Master of Kung Fu had a rocky start. The early stories, under Englehart and Starlin, hewed closely to the Kwai Chang Caine model, with Shang-Chi as a purely reactive character. Marked for death by his father, Shang-Chi would stumble into some trap, fight off Fu Manchu’s assassins, and stumble out again, with little sense that the story was going anyplace. The quantum leap came with the arrival of a new creative team, writer Doug Moench and artist Paul Gulacy. Explicitly rejecting the passive mode of the first year, Moench and Gulacy’s first storyline found Shang-Chi actively throwing in his lot with Smith by joining his team of covert operatives. Fu Manchu retreated into the background as Smith’s motley crew — Shang-Chi, suave secret agent Clive Reston, aging hardcase Black Jack Tarr, femme fatale Leiko Wu, tormented demolitions expert James Larner — went up against the weirdest rogues’ gallery in comics. Mad scientists who truly seemed mad, drug-runners with delusions of grandeur, cyborgs with daddy issues, lovelorn Hong Kong gangsters, even shape-shifting robots with pop-culture fixations — we’d never seen sick puppies like this.

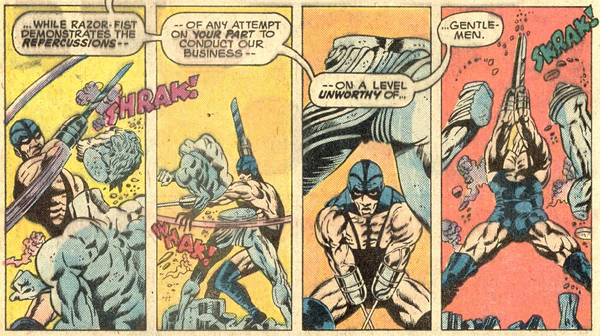

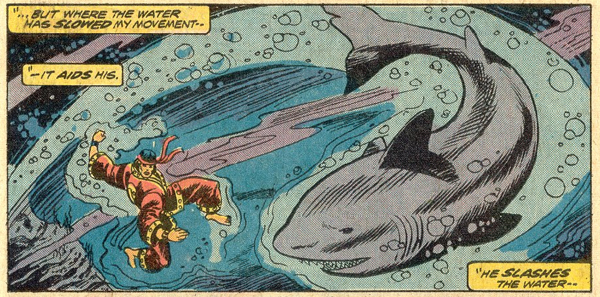

As MoKF explored the uneasy interzone of martial arts and superheroics, it continually circled back to a note of what we would today call ”body horror.” In the pages of, say, Iron Man or Daredevil, a villain like Razor-Fist — a double amputee in a wrestling singlet, luchador mask, and thigh-high bitch boots — would scarcely even register among all the other weirdos in their super-powered fetish suits. But in MoKF’s more naturalistic world (albeit only marginally more naturalistic, replete as it is with secret agents and criminal masterminds with robot armies and hidden island headquarters), the sheer oddness of the conceit is glaring. The same goes for other recurring baddies, like Shadow-Stalker, a half-naked giant with a double-headed flail in his hair, or Pavane, a lash-flicking vixen in a leather bikini. The grotesquerie is almost camp, with a self-referentiality that rubs our faces in just how kinky the typical super-hero comic is, in its psychosexual undercurrents.

Fu Manchu is offstage for long stretches, but he casts a shadow over the entire series — so that when he does occasionally emerge, he gains a renewed grandeur. His periodic appearances, in massive, intricate story arcs unfolding over a year or more’s worth of issues, feel truly epic.

And it’s all delivered with wit and flair. Moench’s long-form plotting is tight and clever, packed with reversals and double-crosses. There’s a moral complexity rare in mainstream comics, a simmering atmosphere of compromise; Shang-Chi must confront quandaries on scales both large (the violence and deception inherent in his role as a secret agent) and intimate (his growing attraction to his best friend’s girl). As with many comics of the 1970s, the dialogue sometimes feels overwritten; but the device of using a first-person narrator — which became ubiquitous during the Terrible 90s — was fresh and lively here, giving the book a unique voice. And even in this, Moench took the experiment one step further; Shang-Chi is the usual narrator, but during one memorable multi-parter the point-of-view rotates to a different character in each issue, from Reston to Leiko to Tarr to Smith and ultimately to Fu Manchu himself.

Paul Gulacy, in his three-year run, balances dynamic draftsmanship with smooth, graceful storytelling. Despite the finely-rendered detail, his figures never look posed or stiff. The pressures of the monthly schedule sometimes show up in his art; he is forced to rely on a catch-as-catch-can selection of inkers, not all of whom serve him well. But he, too, pushes the boundaries of comics storytelling, integrating narrative strategies borrowed from Japanese manga, Eurocomics, and the cinematic New Wave. His bold compositions, crisp linework and deep, moody blacks leap off the cheap newsprint.

The book is packed with references and allusions to delight the pop-culture hound. Gulacy borrows the likenesses of film stars for characters both major and minor; Moench plays metafictional games, broadly hinting that Reston is the illegitimate son of James Bond. There are homages to Astro Boy, to Enter the Dragon, to The Seven Faces of Dr. Lao. And the characters themselves — unusually for genre fiction — actually interact with pop culture. They are aware of, and comment on, the kung fu craze. They buy Fleetwood Mac records, they hang Frank Frazetta posters on their walls, they go to see current movies in between world-saving missions. The specificity of the references dates the stories, but it also gives them a certain believability, despite all the fantastic goings-on. These people’s lives may revolve around stopping an immortal megalomaniac from blowing the Moon out of orbit, but they still find time to listen to Rumours — just like you!

So, yeah. Ground-breaking stuff, well worth your time. But you’ll probably never see it reprinted.

Partly, that’s for legal reasons. When Master of Kung Fu was finally canceled in 1983, following a long, slow decline in sales, Marvel Comics as yet had no trade paperback program in place, no strategy for reprinting or re-releasing its archives in book form. Once the material had been out of print for a few years, the rights reverted to the Rohmer estate. Marvel was publishing a lot of licensed material at the time, much of it better than it needed to be, which is now stuck in the same legal limbo — popular books, denied the chance to reach an audience after their original run, simply because of the peculiar business model under which they were produced.

But even if the legal issues were somehow resolved, it’s doubtful that Master of Kung Fu would ever be reprinted — because Fu Manchu has become an untouchable character. The Devil Doctor is now a symbol of attitudes that were once all too prevalent, attitudes that we would prefer to forget. Such a character can never again be played straight; the only way to approach the archetype is through a protective layer of irony — as was done with the Mandarin, in Iron Man 3 — and even then you risk giving offense. (The fact that China is now the biggest overseas market for US films only compounds the irony — and the risk.)

Fu Manchu was always a problematic character in this respect. The Fu Manchu films were the subject of protests and petitions as early as 1932. During World War II, with China joining the Allies in the fight against imperial Japan, Rohmer’s publishers suspended the series, leading to a seven-year gap between books, and the US State Department shut down production of a Republic Pictures film featuring the character. Even when the franchise was revived in the late 1950s, there was a sense that Fu Manchu had become an embarrassment; Christopher Lee played Fu in five films in the 1960s, but these have rarely been shown on TV because of pressure by anti-defamation groups. By the late 70s, the character’s reputation had become so toxic that even The Fiendish Plot of Dr. Fu Manchu — a blatant satire starring Peter Sellers — was greeted with protests.

Is this reputation deserved? Certainly Fu Manchu, as originally conceived, is a vile caricature, and Rohmer’s early books are filled with casual anti-Asian slurs and nativist rhetoric. Rohmer — who had once been a newspaper reporter, covering the Limehouse crime beat — offered the the mealy-mouthed ”Hey, some of my best friends are Chinese” excuse so typical of the bigot. In his autobiography, he wrote: ”Of course, not the whole Chinese population of Limehouse was criminal. But it contained a large number of persons who had left their own country for the most urgent of reasons. These people knew no way of making a living other than the criminal activities that had made China too hot for them.”

It’s a favorite tactic of racist ”thought,” this selective reading of the evidence, this conflation of correlation and causation. And we still hear it in right-wing circles today: ”I’m not saying that all blacks are criminals,” they’ll say, ”but it’s an undeniable fact that the prison population is disproportionately African-American” — as if skin color alone, rather than, say, lack of economic opportunity, is a predictor of criminality. ”I’m not saying all Muslims are terrorists,” they’ll say, ”but most terrorists are Muslims” — conveniently ignoring that most of those Muslims who embrace terrorism live under autocratic regimes with no other venue for political dissent. It’s fallacious reasoning at best, cynical bullshit at worst. It’s nonsense now, and it was nonsense a hundred years ago.

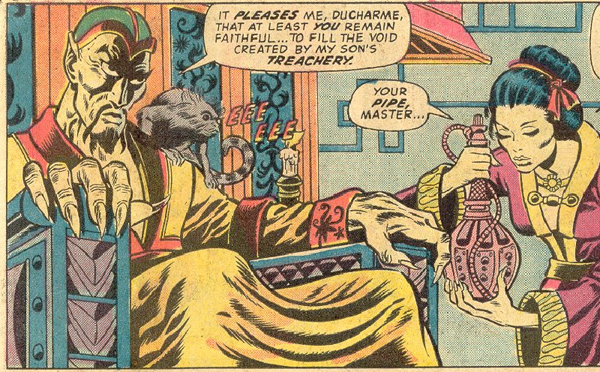

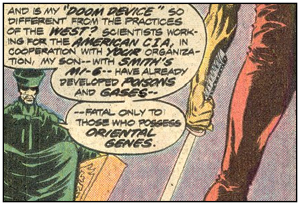

Even in Master of Kung Fu, there’s some visual stereotyping. There are none of the slitty-eyed, buck-toothed caricatures that make (say) the 1940s Blackhawk so excruciating to read, but the inconsistencies of the coloring are troublesome. The jaundiced yellow skin tones of Fu Manchu and Shadow-Stalker, seen above, are pretty horrific, especially given that most of the other Asian characters are colored more realistically. (Oddly, Shang-Chi’s unnatural orange pigmentation doesn’t ”read” as stereotypical, as he is the only character, Asian or Western, to be so colored. It marks him out, giving a unique visual signature as a literal and metaphorical ”golden boy.”)

But MoKF’s very premise mitigates the racist aspect of the Fu Manchu character somewhat, simply by placing him in opposition with another Asian character. (Marvel employed this same strategy with its 1950s villain the Yellow Claw, shown at left: his sinister plans were thwarted by a heroic Chinese-American FBI agent named Jimmy Woo.) The dynamic of Yellow Peril vs. White Supremacy is recast as an expression of the Generation Gap. Fu Manchu becomes an explicitly conservative figure, trying to turn back the clock and remake the world in the image of his beloved ”Old China” — an idealized vision of a simpler time, uncorrupted by decadent modernism, when the races didn’t mix and everybody knew their place; a time before Communism, before the misguided egalitarianism of democracy, where a strong man could work his will in the world without all those pesky laws holding him back. (Tea originated in China, and apparently so did the Tea Party.) Shang-Chi is the progressive, the modernist, the multi-culturalist, taking the world as he finds it, non-judgmentally, and keeping what works. He makes friends easily with characters of all races, learns to love pizza and Spielberg and Exile on Main Street, all without sacrificing his ethnic identity or his Taoist values.

Writer Doug Moench is a white liberal, and he works to give even Fu Manchu a certain dignity, portraying his anti-Western xenophobia as a reaction to Occidental racism, ”the hate that hate produced” — Malcolm X as supervillain. But from our contemporary viewpoint, where race is understood as primarily a social construct, we still find in Master of Kung Fu some jarring notes of racial essentialism. Certainly a panel such as this one (at right) must give us pause.

The letter columns in these old comics are revelatory in their own way, showing both how much and how little progress has actually been made. The readers of the 1970s were just as taken with the artfulness of MoKF as we are today, and just as troubled by some aspects of the representation. But Moench, to his credit, uses his characters to confront the topic of race head-on, without preaching. With Shang-Chi as a catalyst, all the characters re-examine long-held assumptions over the course of the series. The good-old-boy Black Jack Tarr simply cannot understand why Shang-Chi would object to being called ”Chinaman,” when it’s obvious that Black Jack doesn’t mean it in a bad way; Leiko Wu, thoroughly assimilated, struggles with her Chinese-British ethnic identity in light of her growing attraction to the FOB Shang-Chi; Nayland Smith tries to reconcile his fatherly affection for the kid with his ingrained distrust of the ”yellow devil”; the Chinese ganglord Cat accuses Shang-Chi of racial sell-out, tauntingly calling him ”Britisher” — though Cat himself has a white girlfriend.

This is complex, provocative stuff, even for 2013. For all its occasional missteps, Master of Kung Fu is not only beautiful, ground-breaking comics storytelling — it advances the conversation on race with a candor and fearlessness not often seen in pop entertainment. It reclaims the Fu Manchu archetype from the realm of camp, only to slyly interrogate and eventually dismantle that archetype over the course of its run. That these stories are only available in moldering back-issue bins seems criminal; it is sad to think that one day they shall be gone forever, as the ravages of time render their pages brittle and discolored — another sort of yellow peril — before turning them to dust.

Comments