Which X-Men do you prefer: the younger First Class generation, introduced in 2011, or their older selves, last seen in 2006? In a cunning move straight from Marvel comics, X-Men: Days of Future Past unites both casts in a deft time-spanning saga that doesn’t lack for breathless thrills, while retaining the relative modesty and emphasis on character dynamics that give the series its appeal.

Which X-Men do you prefer: the younger First Class generation, introduced in 2011, or their older selves, last seen in 2006? In a cunning move straight from Marvel comics, X-Men: Days of Future Past unites both casts in a deft time-spanning saga that doesn’t lack for breathless thrills, while retaining the relative modesty and emphasis on character dynamics that give the series its appeal.

Released in 2000, well before The Avengers began assembling in theaters, the original X-Men didn’t seem like one of the great superhero movies. In the onslaught since it’s held up remarkably well, not at all bloated by excessive origins stories and, at what seems today an impossibly brief 104 minutes, swiftly executed. With director Bryan Singer again at the helm the 2003 sequel built on its success; without him, it muddled into mutant overload three years later, and spinoffs with Hugh Jackman’s Wolverine haven’t had the same lift. I liked First Class, which reminded me of why I enjoyed the concept in the first place, though I can’t say it left me hungering for more.

Days of Future Past returns Singer to the director’s chair, and while he might do well to heed in his checkered personal life the speeches about respect and responsibility that dot the films he certainly knows how to marshal an X-Men movie. Fans will get their geek on. Mind you I can’t say I’m fully conversant; just as at Christmas it helps to be grounded in subjects like slavery, financial markets, and gravity, so, too, is knowledge of comic books an asset in summer. I was bombarded (pleasantly so, as these movies go) with X-powers yielded by characters I either didn’t know or who are sketched in just enough for the hardcore to recognize.

So let me take inventory of who I did know. The film begins ten or so years in a blighted future, where man and mutant have fallen under the reign of the Sentinels, robots that have gone far beyond their mandate to eradicate the X-race. Ensconced in a Chinese temple, the surviving mutants have one last play left, to mind-meld Wolverine back to 1973 to rally the divided troops and prevent the shape-shifting Mystique from killing the Sentinels’ creator, a well-intentioned assassination with unforeseen ramifications. By necessity much of the heavy lifting is done by Jackman and the First Class castmembers, as the original team wards off those pesky Sentinels.

So let me take inventory of who I did know. The film begins ten or so years in a blighted future, where man and mutant have fallen under the reign of the Sentinels, robots that have gone far beyond their mandate to eradicate the X-race. Ensconced in a Chinese temple, the surviving mutants have one last play left, to mind-meld Wolverine back to 1973 to rally the divided troops and prevent the shape-shifting Mystique from killing the Sentinels’ creator, a well-intentioned assassination with unforeseen ramifications. By necessity much of the heavy lifting is done by Jackman and the First Class castmembers, as the original team wards off those pesky Sentinels.

Given an unwieldy scenario that could shred at any moment, Days of Future Past is reasonably unified by screenwriter Simon Kinberg, and has a surprising lightness to it, a quality forbidden in the gloomier, heavier Dark Knights and Man of Steel produced over the last fifteen or so years. (That this has a post-apocalypse setting, albeit in the boxoffice-rich market of China, makes that all the more remarkable.) Most of the fun comes from Wolverine’s interaction with characters he met only briefly as younger people in First Class–the broken-hearted, hippie-ish Xavier (James McAvoy) and the unrepentant Magneto (Michael Fassbender), who twists the situation to his advantage. Much of their bickering is over the soul of the errant Mystique. Jennifer Lawrence has gone into Oscar-winning supernova since 2011, and the film gives her as much screen time as possible, and as many 70s outfits (American Hustle castoffs?), male or female, as she can wear. The future gets shorter shrift: Patrick Stewart is his usual ruminative self as Xavier (who gets to “meet” McAvoy in a good scene), while the mind-melded Kitty Pryde (Ellen Page) has little to do save for beware of Jackman’s claws, Halle Berry’s apparently ageless Storm hurls thunderbolts, and Ian McKellen’s Magneto looks tired and dyspeptic. Hobbit fatigue?

More lively is Peter Dinklage, as the prejudiced scientist villain, who is aligned with Wolverine’s nemesis Stryker (Josh Helman) and the Nixon administration. Better still is Quicksilver (Evan Peters), who in the film’s showstopper whips through the Pentagon in “bullet time” to free Magneto. Laugh out loud stuff from the funny pages, and worth upgrading to 3D for. Even in 2D, Days of Future Past is a buoyant experience.

Oh, and be sure to stay through the closing credits for a teaser. X-philes should have no trouble placing it. I had to look it up on Wiki.

I’ve minored in Godzilla studies since childhood, and the second attempt at an American Godzilla is mostly a winner. The “American” is key. We can’t really remake Gojira (1954), which is so specifically, heart-wrenchingly Japanese in its atomic era sadness that it can’t be ported over, even after decades of friendlier sequels beloved by kids of all ages. Godzilla 2014 is to Gojira what The Magnificent Seven (1960) is to The Seven Samurai, Toho’s other blockbuster sixty years ago; an affectionate appropriation that stands apart.

I’ve minored in Godzilla studies since childhood, and the second attempt at an American Godzilla is mostly a winner. The “American” is key. We can’t really remake Gojira (1954), which is so specifically, heart-wrenchingly Japanese in its atomic era sadness that it can’t be ported over, even after decades of friendlier sequels beloved by kids of all ages. Godzilla 2014 is to Gojira what The Magnificent Seven (1960) is to The Seven Samurai, Toho’s other blockbuster sixty years ago; an affectionate appropriation that stands apart.

That it stands at all, after the cringing disaster of the 1998 one (two words: Maria Pitillo), is itself a miracle. Moved up to the majors after the card-calling success of 2010’s low-budget Monsters, director Gareth Edwards endeavored for a kitsch-free reboot, and got it, maybe too much so for some. Even when San Francisco is falling apart, it’s muted, and plays its cards close to its chest, saving the good stuff for the final act. I don’t think he’s being perverse when he cuts away from unfolding mayhem, or lets it play across TV and monitor screens; rather, being an A student in the subject, he knows that too much Godzilla is bad for a Godzilla movie (those innumerable battles on budget-conscious rocky outcroppings in the sequels don’t age well for anyone above the PG-13 rating) and keeps him in reserve. For once a grand finale to an expensive summer tentpole is truly grand, wiping away the earlier unsteadiness as the film tries to balance CGI and character.

And, to be sure, Godzilla has uncertain passages, and miscalculations. (One was giving a somber Ken Watanabe the name “Dr. Serizawa”; this doctor makes none of the moral choices his 1954 predecessor makes, choices that knocked me for a loop as a child and still haunt me today.) As someone with a high tolerance for the likes of, say, Josh Hartnett, an inflexible Aaron Taylor-Johnson didn’t really bother me–strange, though, that Bryan Cranston is given short shrift. By rights it’s his journey through our strange new world of Godzilla, and the coming together of the snapdragon MUTOs after 15 years ago was clearly meant to echo his reunion with his son and family after an equivalent time apart. His dispatch (hey, it’s been a week!) cripples that connection. Emotionally, the movie’s big moment, toward the end, goes to the bereft MUTOs, which is wrong. What happened here? (Is it an homage to Cranston’s actor dad, who was killed by a giant grasshopper in 1957’s Beginning of the End?)

I could go on; other than the main players the supporting cast is as stiff as Cranston’s hairpiece, and Edwards has trouble getting more than two people in a room together talking believably. Alexandre Desplat’s score for The Grand Budapest Hotel is truly magical; this one is merely functional, as if littler, quirkier films are his true calling. The 3D is a wash. But I’m throwing too much red meat to the loyal opposition, who want more American Godzilla, and, not unreasonably, more about the creature, in the next American Godzilla movies. Fortunately, due to Edwards’ shrewd choices where it counts, we’ll get it, via two planned sequels. With luck, we’ll get more Japanese Godzilla movies, too.

What happens when an auteur loses his mojo? For Atom Egoyan, Devil’s Knot, a film closer in spirit to a passable HBO movie of the mid-90s than his brilliant run from the late 80s to The Sweet Hereafter (1997), where he applied his fascinating, elliptical style to a gripping adaptation and came up with an Oscar-nominated modern classic. The years since have been increasingly, painfully dire. Devil’s Knot isn’t bad…which is to say, it’s a step up, only, from the ash heaps of Adoration, Chloe, and Where the Truth Lies, the last a particularly wretched descent. It’s remission, not progress.

What happens when an auteur loses his mojo? For Atom Egoyan, Devil’s Knot, a film closer in spirit to a passable HBO movie of the mid-90s than his brilliant run from the late 80s to The Sweet Hereafter (1997), where he applied his fascinating, elliptical style to a gripping adaptation and came up with an Oscar-nominated modern classic. The years since have been increasingly, painfully dire. Devil’s Knot isn’t bad…which is to say, it’s a step up, only, from the ash heaps of Adoration, Chloe, and Where the Truth Lies, the last a particularly wretched descent. It’s remission, not progress.

After four documentaries this is the fifth rehashing of the story of the infamous “West Memphis Three” and their two-decade odyssey through the backwaters of Arkansas justice, as claims of satanic cultism further inflamed charges of child homicide. It’s an infuriating episode on many levels, skillfully, passionately told in the prior accounts, but this feature just sits there, cold to the touch, idling. The movie foregrounds the investigation and the families of the victims (Reese Witherspoon is the mother of one of them) but that isn’t where fascination in the case resides, and it ends up recounting a story we already know from an angle that isn’t particularly edifying. Colin Firth, who survived Lies to come back for more punishment (and whose career post-Academy Award is at a Cuba Gooding, Jr., level of decay), overworks a ridiculous accent as a detective (who said Brits are better at playing Americans than the other way around?) and a large cast that includes reliables like Amy Ryan and Mirielle Enos is left stranded for lack of focus and a strong POV. Only Kevin Durand, as the strangest and most dominant of the slain boys’ father, shakes up a by-the-numbers treatment. The word from Cannes is that Egoyan’s latest, The Captive, is atrocious. Sad.

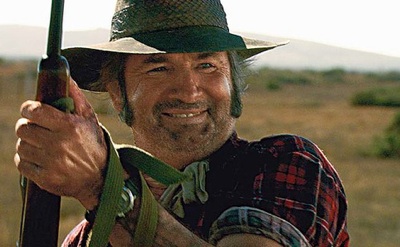

Not sad, rather, perplexing, is the case of Australia’s Greg McLean, who on the basis of two superior horror films, Wolf Creek (2005) and Rogue (2007), should have advanced to bigger and better things: a superhero movie? A redo of a horror classic from the 70s and 80s? Hmm, maybe lack of appealing options is the problem. But after a too-long hiatus Wolf Creek 2, flying, like Devil’s Knot, under the radar mostly on VOD, isn’t much of a solution.

Not sad, rather, perplexing, is the case of Australia’s Greg McLean, who on the basis of two superior horror films, Wolf Creek (2005) and Rogue (2007), should have advanced to bigger and better things: a superhero movie? A redo of a horror classic from the 70s and 80s? Hmm, maybe lack of appealing options is the problem. But after a too-long hiatus Wolf Creek 2, flying, like Devil’s Knot, under the radar mostly on VOD, isn’t much of a solution.

It’s not that his filmmaking chops have abandoned him; it’s a solid piece of work, just more of the same, not terribly unalike except in tone. John Jarratt, Quentin Tarantino’s Ozploitation crush object, returns as the Outback serial killer Mick Taylor, who is as garrulous as he is murderous. This time, in between rounds of trapping, hammering, and decapitating, he’s talking his tourist victims to death, most amusingly in a scene where he grills one about Australian facts and figures as he removes fingers for incorrect answers. Supported once more by eerie cinematography of the near-lunar topography, the actor is pretty much the whole show here, and he is again infectious in his homicidal glee. The difference is that the first time the laughter caught in our throats as he gloated over the spinal cords of his prey; inevitably, with the notion of a franchise hovering, he’s been Krueger-ized, tamed and made more palatable for further sequels. But do we really need anyone to throw more shrimp on this barbie? Perhaps McLean figured that if he didn’t do it, someone else would, and paternal instinct kicked in. Sometimes sticking with one child is best, however.

And if none of this appeals to you, the highly commendable Chef, Locke, Under the Skin, and Jodorowsky’s Dune, a documentary about a fantasy film spectacular that was not to be, are still kicking around on screens somewhere. Something for everyone over the long weekend.

Comments