I’m not here to pass judgment on what gets you off, friends; let’s get that straight. My job, when I’m wearing my ”critic” hat, is to look at the things you like or dislike and make an informed call about whether or not they succeed as Art. It’s not a verdict on  you. Your likes or dislikes don’t enter into it. Hell, I harbor an unashamed love for all sorts of things that don’t entirely succeed artistically — Big Trouble In Little China, most of Chuck Palahniuk’s books, latter-day Big Country records, Lost — and that doesn’t make me a bad person. (There are plenty of other things that make me a bad person, but loving Big Trouble In Little China isn’t one.)

you. Your likes or dislikes don’t enter into it. Hell, I harbor an unashamed love for all sorts of things that don’t entirely succeed artistically — Big Trouble In Little China, most of Chuck Palahniuk’s books, latter-day Big Country records, Lost — and that doesn’t make me a bad person. (There are plenty of other things that make me a bad person, but loving Big Trouble In Little China isn’t one.)

An intriguing misfire requires no defense, as it trumps stultifying perfection any day. We fall for interesting failures because of the same thing that makes them fail in the first place: their outsized ambitions. The trash that wins our hearts is trash that aims high. Everybody loves an underdog, and watching a scrappy contender taking chances, making a bid for profundity or catharsis or style, all in the knowledge that they’re punching above their weight — there’s something kind of beautiful about that.

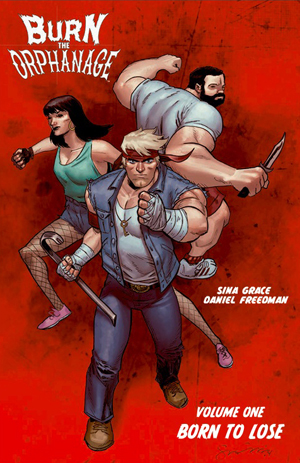

Every once in a while, though, something comes along that’s nearly impossible to evaluate, either as art or trash, because you’ve got no fucking clue what it’s trying to achieve. That’s the position in which I find myself with the irregular comics series Burn the Orphanage, the first collected edition of which, subtitled Born To Lose, has just been released.

Burn the Orphanage, perhaps not coincidentally, is all about scrappy underdogs facing long odds. It’s the creation of two dudes, Daniel Freedman and Sina Grace. Lifelong friends. One is straight, one gay; one writes, one draws. They’ve been kicking around the comics industry for a few years now, doing bits and bobs for major publishers and indies alike, while maintaining parallel careers in film, game design, and illustration.

Burn the Orphanage is published through Image Central, which operates unlike more traditional publishers in that creators retain full ownership rights of their properties in exchange for a fixed administrative fee. Creators assume all the upfront costs for production; in return, they get the use of Image’s branding, promotion, and distribution apparatus.

It’s a system tailor-made for high-concept passion projects; stuff with enough sales potential to promise a return on investment, but too quirky, too meaningful for the corporate editorial machine. In practice, this often means off-kilter takes on established genres, like Matt Fraction and Chip Zdarsky’s NC-17 farce Sex Criminals, the supernatural western Pretty Deadly by Kelly Sue DeConnick and Emma Rios, or John Layman’s bizarre police procedural Chew. Commercial work, but not blanded-out or dumbed down.

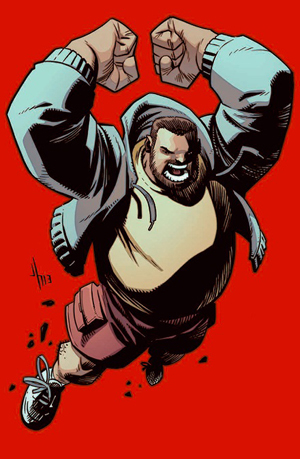

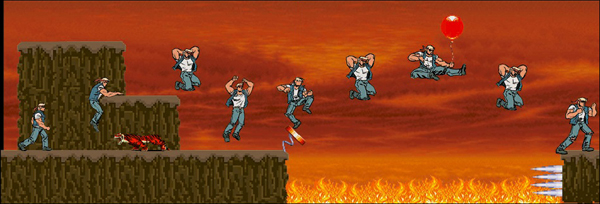

Burn the Orphanage is a commercial prospect. The book is pitched to the sizeable market for 80s and 90s videogame nostalgia, evoking classic side-scrolling beat-em-ups like Street Fighter and Tekken. The hero, Rock Hard (…yeah), came up in that orphanage; when he grows to beefy, bandanna-clad adulthood, he sets out to wreak vengeance on the slumlord who had it torched. Two neighborhood buddies have Rock’s back: Bear — a burly, beardy gay bro with the transplanted heart of a genuine Ursus arctos beating in his barrel chest — and Lex, a lithesome bad girl with a hair-trigger temper and a complicated love life.

Burn the Orphanage is a commercial prospect. The book is pitched to the sizeable market for 80s and 90s videogame nostalgia, evoking classic side-scrolling beat-em-ups like Street Fighter and Tekken. The hero, Rock Hard (…yeah), came up in that orphanage; when he grows to beefy, bandanna-clad adulthood, he sets out to wreak vengeance on the slumlord who had it torched. Two neighborhood buddies have Rock’s back: Bear — a burly, beardy gay bro with the transplanted heart of a genuine Ursus arctos beating in his barrel chest — and Lex, a lithesome bad girl with a hair-trigger temper and a complicated love life.

As with any fighting game franchise, the stakes get higher and the foes get harder as the series progresses. The first story finds Rock and friends plowing through an army of mooks on their way to the inevitable boss battle. In the follow-up, Rock is summoned to a mysterious island to compete in a Mortal Kombat-style elimination tournament, dueling a roster of demons, aliens, and extradimensional nasties; then it’s off to outer space to fight giant psychedelic monsters. This volume ends on a cliffhanger, with Rock returning to a dystopian future version of his hometown to face a powered-up version of his original nemesis. (This second long storyline, ”Reign of Terror,” is currently in serialization.)

The thing is, I’ve probably made this sound more entertaining than it actually is. There’s a purposefully ramshackle, Adult Swim kind of vibe going on — Burn the Orphanage is definitely aimed at a similar demographic — but the execution has the shaggy, stoner lope of an Aqua Teen Hunger Force, when the premise cries out for the more focused mayhem of a Metalocalypse. The book serves up heaping helpings of bad taste, titties, and the old ultraviolence, but without the lunatic energy of antecedents like the Dragonball manga or Scott McCloud’s seminal indie slugfest Destroy!! Even the big set piece of chapter 2 — an impromptu castration — is weak cheese compared to the body-horror antics of Cannibal Fuckface and his pals in Johnny Ryan’s gonzo bloodbath Prison Pit. When we look at the games that inspired it, there’s nothing in Burn the Orphanage to match Mortal Kombat’s infamous spine rip fatality, to say nothing of the batshit-crazy finishing moves of underground legend Tattoo Assassins. It’s as if Burn the Orphanage cannot fully commit to its own trashiness.

Indeed, at times it seems to lack any clear idea of what sort of book it wants to be. Scenes of Rock whooping asses will crosscut with Bear and Lex eating hamburgers and talking about their dating histories. Which might be interesting if either of them were an actual character, rather than merely a type (albeit, in Bear’s case, a type we rarely see in mainstream comics). Perhaps it’s by design — as a sideways ”tribute” to the thin backstories of videogame characters — that Burn the Orphanage keeps the characterization as scanty as Lex’s fishnets-and-booty-shorts wardrobe. But again, the book can’t commit, and interjects flailing attempts at development that play like talky, unskippable cut-scenes, bogging the story down just when the craziness should be escalating.

The attempts at comedy are worse, trading on the Family Guy model that pop culture references are in themselves intrinsically hilarious. There’s an extended riff on 2 Broke Girls, for cry-eye; who the fuck even watches stuff like 2 Broke Girls?

Sina Grace’s artwork occasionally elevates the scripting. There are a few amusing gestures towards the lo-rez pixealtion of the source material, and in the midst of the tournament sequence Grace devotes an entire splash page to a Sweet Sixteen-style bracket, rendered in glorious, whacked-out detail. In Grace’s modelling there are nostalgic echoes of the Buscema brothers — John and the nine-years younger Sal — who in the 1970s and 80s codified the Marvel house style (indeed, John would go on to literally write the book on How To Draw Comics the Marvel Way). Their systematic refinement of Jack Kirby’s innovations slicked the King’s rough edges to lay the groundwork for a generation of artists who, while not overt Kirby Klones, were recognizably part of the movement he inadvertently founded. Their is not a particularly fashionable influence today — second-wave journeymen like the Buscemas never had the cachet of OG pioneers like Kirby or Ditko — but it’s undeniably present in Rock’s frequently-shirtless physique, which, like Conan the Barbarian’s, is bulky but strangely sleek; in the shouts and grimaces; in the gravity-defying leaps of the fight scenes; in the grotesque horns and armor of the aliens and demons.

Sina Grace’s artwork occasionally elevates the scripting. There are a few amusing gestures towards the lo-rez pixealtion of the source material, and in the midst of the tournament sequence Grace devotes an entire splash page to a Sweet Sixteen-style bracket, rendered in glorious, whacked-out detail. In Grace’s modelling there are nostalgic echoes of the Buscema brothers — John and the nine-years younger Sal — who in the 1970s and 80s codified the Marvel house style (indeed, John would go on to literally write the book on How To Draw Comics the Marvel Way). Their systematic refinement of Jack Kirby’s innovations slicked the King’s rough edges to lay the groundwork for a generation of artists who, while not overt Kirby Klones, were recognizably part of the movement he inadvertently founded. Their is not a particularly fashionable influence today — second-wave journeymen like the Buscemas never had the cachet of OG pioneers like Kirby or Ditko — but it’s undeniably present in Rock’s frequently-shirtless physique, which, like Conan the Barbarian’s, is bulky but strangely sleek; in the shouts and grimaces; in the gravity-defying leaps of the fight scenes; in the grotesque horns and armor of the aliens and demons.

Yet there’s a reification that sets in along chains of influence. Along with the merits of his models, Grace inherits their vices — an over-reliance on stock faces and poses, and an … interpretive sense of anatomy, let’s say. Dynamism shades into distortion, dramatically foreshortened limbs becoming rubbery and twisted. You could forgive i fratelli Buscema the occasional duff panel — theirs was artistic production on an industrial scale, and with the two of them sending hundreds of pages flying out the door each month, not every frame was going to be gold — but with Grace it seems a deliberate stylistic choice.

Like so many of the artistic choices in this promising, frustrating book, it serves only to baffle. Any miss is as good as a mile, but there’s naught so disappointing as the joke that doesn’t quite land; and Burn the Orphanage hovers like a worried hornet, never settling on any definite tone or mood. The bones of another, better book are visible beneath the skin, but Burn the Orphanage can never quite excavate them — no matter how much blood it spills in trying.

Comments