”No one plays Gershwin anymore,” laments Julian Velard in ”That Old Manhattan,” the penultimate and one of the standout tracks from his exceptional new album, If You Don’t Like It, You Can Leave, which is being released June 17. As if to accentuate his point, in the chorus he throws in the main riff from ”Rhapsody in Blue” on the piano, albeit modified for 3/4 time.

”No one plays Gershwin anymore,” laments Julian Velard in ”That Old Manhattan,” the penultimate and one of the standout tracks from his exceptional new album, If You Don’t Like It, You Can Leave, which is being released June 17. As if to accentuate his point, in the chorus he throws in the main riff from ”Rhapsody in Blue” on the piano, albeit modified for 3/4 time.

That’s a sentiment I understand completely. Growing up on Long Island in the ’70s and ’80s, I continuously heard about how far New York City had fallen. Its post-war glory days — romanticized in musicals of the day like On the Town and Wonderful Town — had long since passed, replaced by an angry, crime-ridden, drug-infested hellscape. But the adults in my life who complained about what they saw on the news every night still said that, despite all its problems, New York was the greatest city in the world.

Underlying the problem was that there were plenty of remnants of the New York of my parents’ generation to be found: Broadway, the architecture, Bobby Short at the Carlyle, whatever movie Woody Allen had just churned out. Even if I was terrified that I might not make it home alive, it still meant something to go into the city a few times a year.

At 34, Velard, who was raised on the Upper West Side, wasn’t even alive during the ”Ford to City: Drop Dead” era. But, as I’ve written here before, he’s an old-fashioned pop craftsman — a tradition that extends through Tin Pan Alley all the way up to Billy Joel, Elton John and Randy Newman. Their spirits are infused throughout the record, where he attempts to reconcile New York’s past with its present. He loves the latter, but his sensibilities are with the former, even if he never experienced it firsthand.

Velard bridges those eras brilliantly, both in his music and lyrics. ”You Don’t Fall in Love at the Start” is a torch song that Chet Baker should have lived long enough to cover, but it expresses a thoroughly modern mindset. Similarly, ”Brooklyn Kind of Love” is a bouncy ditty, complete with Cole Porter-esque inner rhymes, about romance in the city’s coolest borough, and thankfully eschews a litany of hipster stereotypes that a lesser writer would have employed.

If You Don’t Like It, You Can Leave takes its title — a common phrase used by the natives — from a line in the opener, ”New York, I Love It When You’re Mean.” It’s the type of ode to the city that hasn’t been written in decades, one where all the sunshine and movie stars in L.A. can’t compare to being lost in the Bronx late at night. ”Give it to me real / I don’t want to live in a dream,” he sings as a chromatic piano riff rises and falls like a drunk stumbling down the street.

When Velard spoke to Jeff Giles here three years ago in support of Mr. Saturday Night, he explained that he created its title character – albeit one not too dissimilar from himself – to vent his frustrations at the way his career had turned out because he was never comfortable with 100% autobiographical songwriting. But on this record, he’s embraced the idea of opening himself up. This extends not just to the concept, but one song in particular. On ”Jimmy Young,” its emotional centerpiece, he tells the story of a piano player that his father used to watch in 1967, and Velard draws a parallel to his own career to devastating effect.

Elsewhere, the album brims with the feel of Velard’s New York. He doesn’t see the alienated ”city of strangers” that Stephen Sondheim wrote about in Company. For him, it’s the Brooklyn bars overlooking the East River and the joys of not owning a car (”That’s what real New Yorkers do”). Just about the only difficulties he finds are in romance, whether it’s the girl next door or in another borough. He closes it, fittingly, with a cover of ”Where’s the Orchestra,” the last song on Billy Joel’s magnum opus, The Nylon Curtain.

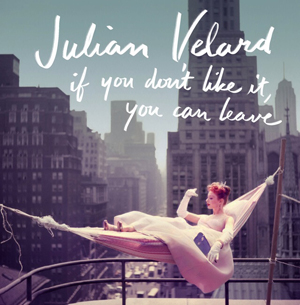

How much If You Don’t Like It, You Can Leave can resonate with listeners beyond the Tri-State area is a mystery, but it doesn’t matter. It’s a complex, but un-ambivalent, look at Gotham, beginning with the cover, which juxtaposes its wiseass title with a 1953 photo of a glamorous Gwen Verdon on a hammock atop a skyscraper. And as much as I love my adopted hometown of Chicago (particularly on the gorgeous day when my copy of the CD arrived), listening to Velard’s album made me a little homesick, for both the new and the old New York.

Comments