The 52nd New York Film Festival saw more of me than in the past few years, as fortunate scheduling allowed me to see eight films during the event, which ended on Sunday, and one more entrant outside Lincoln Center. Of course, I suffered for it. Festival films, whether destined for the arthouse, VOD, or the Oscars, tend to come cloaked in darkness, and this year was no exception. Emotional and physical violence were the order of the day–thankfully, the best of the slate allowed me to revel in misery.

The 52nd New York Film Festival saw more of me than in the past few years, as fortunate scheduling allowed me to see eight films during the event, which ended on Sunday, and one more entrant outside Lincoln Center. Of course, I suffered for it. Festival films, whether destined for the arthouse, VOD, or the Oscars, tend to come cloaked in darkness, and this year was no exception. Emotional and physical violence were the order of the day–thankfully, the best of the slate allowed me to revel in misery.

I started with a favorite now old enough for golden oldie status, a restored version of Sergio Leone’s time-spanning masterwork Once Upon a Time in America. Was it really 30 years ago that I writhed through its abortive theatrical release, minus 80 or so minutes and brutally shorn of its delicate structure? Yes, it was, and I was stupefied; was there actually something worth saving in the mishmash served up to multiplexes? A few months later, on a frigid winter’s day in Chicago, I had my answer–a resounding “yes,” as the 229-minute version proved a revelation, and gave me one of my finest moviegoing experiences. (It was damn cold out that day, and worth braving frostbite conditions.) I hadn’t revisited it in years, until an Italian Blu-ray running 251 minutes surfaced a year or two ago. Sad to say the thing was a disaster, a chalky, milky mess, dumbed down in appearance to match the barely YouTube-quality footage swept up from the cutting room floor.

The DCP shown at the festival was gorgeous, as is the subsequent Blu-ray–except for those appalling scenes, which are also hard to hear. Periodically this visual and sonic graffiti defaces the presentation, for no good reason. Louise Fletcher’s useless sequence as “the cemetery directress” is back, and Treat Williams, Elizabeth McGovern and Darlanne Fluegel get some additional, clarifying footage, though most of what they do can be inferred in the existing assembly. The better alternative would have been to use this stuff as deleted scenes, as cutting them back into the film does it no favors. So another lousy “director’s cut,” extended without the long-deceased filmmaker’s approval–yet how nice it was to have it introduced by stars Robert De Niro (right before he went from a commandingly still to a bullyingly shrill presence onscreen), James Woods (providing high-voltage contrast), Williams, William Forsythe, and Scott Schutzman Tiler (the “young Noodles” is now 43, two years older than De Niro when the film was released–and only a few years younger than myself. Time flies…)

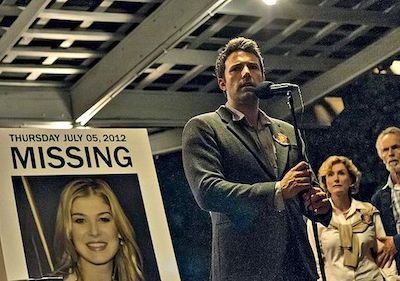

The festival opened with the current movie of the moment, Gone Girl. As usual tickets for that one vanished quick (as they did for the “Centerpiece,” Inherent Vice, and the closing attraction, Birdman) so rather than fight with the balky online ticketing system, which can make you wish for the olden days of checks and checklists and envelopes, I saw it at New York’s premier venue, the Ziegfeld. There I confirmed the burning question: Yes, you can see Ben Affleck’s peen, a quick lateral view as he enters the shower toward the end of the film, so low in the frame careless (or more careful?) projection might crop it out. Other than that, I also confirmed that David Fincher is a commanding filmmaker–once again outclassing a pulpy scenario, as he did with The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and House of Cards. Technique butts against an overplotted, ultimately harebrained series of chess moves that pit a wife against her husband, with abundant contrivances (like a media circus that conveniently disappears long enough for Affleck to fly to New York to uncover information) across a longish two and a half hours.

The festival opened with the current movie of the moment, Gone Girl. As usual tickets for that one vanished quick (as they did for the “Centerpiece,” Inherent Vice, and the closing attraction, Birdman) so rather than fight with the balky online ticketing system, which can make you wish for the olden days of checks and checklists and envelopes, I saw it at New York’s premier venue, the Ziegfeld. There I confirmed the burning question: Yes, you can see Ben Affleck’s peen, a quick lateral view as he enters the shower toward the end of the film, so low in the frame careless (or more careful?) projection might crop it out. Other than that, I also confirmed that David Fincher is a commanding filmmaker–once again outclassing a pulpy scenario, as he did with The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and House of Cards. Technique butts against an overplotted, ultimately harebrained series of chess moves that pit a wife against her husband, with abundant contrivances (like a media circus that conveniently disappears long enough for Affleck to fly to New York to uncover information) across a longish two and a half hours.

Outside of the absence of a trademark wow of an opening credits sequence I didn’t mind Gone Girl, and I’m glad to see that Rosamund Pike has made it to the majors, though I can’t say it’s inspired me to add to the reams of hot-button prose already generated about misogyny, femme fatales, and the death of marriage. To wit: “The bat-shit preposterousness of the marital ‘accord’ ultimately reached by Nick and Amy is an indictment of the state of marriage, and of heterosexual relations more broadly.” I mean, after that, what is there left to say? Credit Fincher and Gillian Flynn for giving the chattering classes something to chatter about–me, I’ll wait till the director gets over his infatuation with the shallow end of the bestseller list, and returns to the richer veins from which sprang Fight Club, Zodiac, and The Social Network.

Festival films that I actually saw at the festival will be released in the coming weeks and months. A debut from Yann Demange, a French-Algerian filmmaker who lives in London, ’71 is a spiritual cousin to Paul Greengrass’ Bloody Sunday (2002), taking place as it does in Belfast a few months before the Irish Troubles exploded into that notorious massacre of civil rights protestors by the British Army. Into the simmering pot of ill-advised tactics, informers, and betrayals goes an injured young “squaddie,” who is forced to rely on the dubious aid of townspeople when he is separated from his unit after a house raid gone wrong. Black Watch playwright Gregory Burke clearly had in mind the classic Odd Man Out (1947), the story of an IRA gunman in the same predicament, in conceiving his story, which is stripped to the bone and tersely, tensely directed by Demange. (A lengthy pursuit down a long corridor is a highlight.) But, like last year’s Palestinian-made drama Omar, this is a political story that refuses to engage much with politics, other than to deliver the less-than-earthshaking news that life in a war zone is hell on ethics and everything else. It does, however, showcase the impressive Jack O’Connell, before his likely breakthrough in Unbroken later this year.

Festival films that I actually saw at the festival will be released in the coming weeks and months. A debut from Yann Demange, a French-Algerian filmmaker who lives in London, ’71 is a spiritual cousin to Paul Greengrass’ Bloody Sunday (2002), taking place as it does in Belfast a few months before the Irish Troubles exploded into that notorious massacre of civil rights protestors by the British Army. Into the simmering pot of ill-advised tactics, informers, and betrayals goes an injured young “squaddie,” who is forced to rely on the dubious aid of townspeople when he is separated from his unit after a house raid gone wrong. Black Watch playwright Gregory Burke clearly had in mind the classic Odd Man Out (1947), the story of an IRA gunman in the same predicament, in conceiving his story, which is stripped to the bone and tersely, tensely directed by Demange. (A lengthy pursuit down a long corridor is a highlight.) But, like last year’s Palestinian-made drama Omar, this is a political story that refuses to engage much with politics, other than to deliver the less-than-earthshaking news that life in a war zone is hell on ethics and everything else. It does, however, showcase the impressive Jack O’Connell, before his likely breakthrough in Unbroken later this year.

An ongoing disaster area we’d rather forget is the setting for Nick Broomfield’s unsettling Tales of the Grim Sleeper, a return to form for the British documentarian after celebrity-driven pieces like Kurt & Courtney (1998) and well-intentioned but forgettable features. Intrigued by the capture in 2010 of a South Central L.A. native suspected in dozens of “crack whore” deaths, the filmmaker perhaps best known for Aileen Wuornos: The Selling of a Serial Killer (1993) took his camera into the neighborhood, where blight continues a generation after Boyz n the Hood. The murders stretched back into the 80s, and as the mayor and police patted themselves on the back for a job well done Broomfield tells an unflattering alternative story, of leads and information overlooked as officials refused to engage with community activists and survivors of the attacks for decades. In emphasizing the efforts of these resilient citizens, most of them women, as the trial only now gets underway, Broomfield restores their dignity, and offers a portrait that is free of stereotypes we’re unable to shake, to the detriment of all.

An ongoing disaster area we’d rather forget is the setting for Nick Broomfield’s unsettling Tales of the Grim Sleeper, a return to form for the British documentarian after celebrity-driven pieces like Kurt & Courtney (1998) and well-intentioned but forgettable features. Intrigued by the capture in 2010 of a South Central L.A. native suspected in dozens of “crack whore” deaths, the filmmaker perhaps best known for Aileen Wuornos: The Selling of a Serial Killer (1993) took his camera into the neighborhood, where blight continues a generation after Boyz n the Hood. The murders stretched back into the 80s, and as the mayor and police patted themselves on the back for a job well done Broomfield tells an unflattering alternative story, of leads and information overlooked as officials refused to engage with community activists and survivors of the attacks for decades. In emphasizing the efforts of these resilient citizens, most of them women, as the trial only now gets underway, Broomfield restores their dignity, and offers a portrait that is free of stereotypes we’re unable to shake, to the detriment of all.

Looking for Hollywood glamor? Forget about David Cronenberg’s latest, Maps to the Stars, which explodes all notions of that, like the heads in Scanners. Adapted from one of Bruce Wagner’s hate letters to L.A. “industry” types, a more earthy body horror than usual abounds: A maniacally self-absorbed movie star (Julianne Moore), finagling to star in a remake of the 60s hit that launched her dead mother’s career, suffers epic constipation on the john while barking orders to her assistant (Mia Wasikowska, her daughter in The Kids Are All Right), who was badly burned in a mysterious accident. A rehabbed 13-year-old child star (Evan Bird) treats everyone shabbily, including his neurotic mom (Olivia Williams) and self-help guru dad (John Cusack), who fights to keep a lid on family secrets. Ghostly visions, incest, and cruelty of various kinds invade Cronenberg’s typically tightly composed and controlled frames, and Robert Pattinson, who occupied a womb-like limo in Cronenberg’s excellent Cosmopolis, drives by as the movie’s one semi-normal character, a limo driver with higher aspirations. Allegedly satiric, the movie titillates us with outrageous behavior, then punishes us for laughing at it. Outside of the committed performances (Moore’s go-for-broke turn won her best actress at Cannes), Maps to the Stars mostly just repels, and though I’ll never revisit Spider (2002) again just to be sure I’m calling it the director’s least interesting film.

Looking for Hollywood glamor? Forget about David Cronenberg’s latest, Maps to the Stars, which explodes all notions of that, like the heads in Scanners. Adapted from one of Bruce Wagner’s hate letters to L.A. “industry” types, a more earthy body horror than usual abounds: A maniacally self-absorbed movie star (Julianne Moore), finagling to star in a remake of the 60s hit that launched her dead mother’s career, suffers epic constipation on the john while barking orders to her assistant (Mia Wasikowska, her daughter in The Kids Are All Right), who was badly burned in a mysterious accident. A rehabbed 13-year-old child star (Evan Bird) treats everyone shabbily, including his neurotic mom (Olivia Williams) and self-help guru dad (John Cusack), who fights to keep a lid on family secrets. Ghostly visions, incest, and cruelty of various kinds invade Cronenberg’s typically tightly composed and controlled frames, and Robert Pattinson, who occupied a womb-like limo in Cronenberg’s excellent Cosmopolis, drives by as the movie’s one semi-normal character, a limo driver with higher aspirations. Allegedly satiric, the movie titillates us with outrageous behavior, then punishes us for laughing at it. Outside of the committed performances (Moore’s go-for-broke turn won her best actress at Cannes), Maps to the Stars mostly just repels, and though I’ll never revisit Spider (2002) again just to be sure I’m calling it the director’s least interesting film.

R-Patz and K-Stew, together again–at least in this review. She gets a far better deal than her Twilight co-star in Clouds of Sils Maria, a return to form for Olivier Assayas, after his aridly autobiographical Something in the Air (a movie whose producer, Marin Karmitz, dismisses as “boring” in the current issue of Cineaste). The new film also has elements of biography, floating and in and out of the movie as freely as the breathtaking cloud formations in the Swiss Alps that give it its title. There a movie star (Juliette Binoche), tired of green screen roles in Hollywood blockbusters, apprehensively considers rejuvenating her career in a revival of her first theatrical triumph, this time playing the elder of its two female parts. In long and compellingly played scenes she rehearses with her assistant (Kristen Stewart), who is semi-permanently attached to smartphones in attending to all other aspects of her employer’s life. A third character, the hot young movie actress (Chloe Grace Moretz) cast as the younger, more desirable woman in the planned revival, enters the scene, trailing tabloid troubles that call to mind Lindsay Lohan–and, insinuatingly, playfully–Kristen Stewart. Exquisitely acted (Binoche and Stewart harmonize beautifully), and that rare movie that handily passes the Bechdel Test, Clouds of Sils Maria delves deeply into the mysteries of aging and acting. Typical of its surprises is an initially hilarious scene where Binoche (recently seen in Godzilla), dismisses the 3D sci-fi movie featuring her would-be co-star, only to have Stewart counter with a thoughtful argument about representation that is very keenly written by Assayas.

R-Patz and K-Stew, together again–at least in this review. She gets a far better deal than her Twilight co-star in Clouds of Sils Maria, a return to form for Olivier Assayas, after his aridly autobiographical Something in the Air (a movie whose producer, Marin Karmitz, dismisses as “boring” in the current issue of Cineaste). The new film also has elements of biography, floating and in and out of the movie as freely as the breathtaking cloud formations in the Swiss Alps that give it its title. There a movie star (Juliette Binoche), tired of green screen roles in Hollywood blockbusters, apprehensively considers rejuvenating her career in a revival of her first theatrical triumph, this time playing the elder of its two female parts. In long and compellingly played scenes she rehearses with her assistant (Kristen Stewart), who is semi-permanently attached to smartphones in attending to all other aspects of her employer’s life. A third character, the hot young movie actress (Chloe Grace Moretz) cast as the younger, more desirable woman in the planned revival, enters the scene, trailing tabloid troubles that call to mind Lindsay Lohan–and, insinuatingly, playfully–Kristen Stewart. Exquisitely acted (Binoche and Stewart harmonize beautifully), and that rare movie that handily passes the Bechdel Test, Clouds of Sils Maria delves deeply into the mysteries of aging and acting. Typical of its surprises is an initially hilarious scene where Binoche (recently seen in Godzilla), dismisses the 3D sci-fi movie featuring her would-be co-star, only to have Stewart counter with a thoughtful argument about representation that is very keenly written by Assayas.

Mr. Turner was introduced by director Mike Leigh, who flattered the audience by praising us for our excellent post-screening questions. That love affair ended abruptly, when the first question asked about Timothy Spall’s Cannes-winning portrayal of renowned landscape artist J.M.W. Turner was, “Did the actual Turner grunt so much?”–to which Leigh gave a quick, pained “yes,” then moved on. Really, however, that was on everyone’s mind, as portions of the performance are rendered inaudible by the actor’s frequent snorts. Unlike Leigh’s last revivification of cultural history, Topsy-Turvy (1999), which focused on a single period in the lives of Gilbert and Sullivan, Mr. Turner spans the last 26 years of the artist’s life, and without the character introductions and title cards found in most biopics you’re likely to find much of it opaque. I did latch on to a few things, like Turner’s reaction to photography, which to some extent makes his work obsolete, and how his close relationship with his father (contrasted with his tangled relations with women) influenced his art. Best perhaps to ignore the grunting and enjoy the film’s handsomely realized cinematography, production design, and music.

Mr. Turner was introduced by director Mike Leigh, who flattered the audience by praising us for our excellent post-screening questions. That love affair ended abruptly, when the first question asked about Timothy Spall’s Cannes-winning portrayal of renowned landscape artist J.M.W. Turner was, “Did the actual Turner grunt so much?”–to which Leigh gave a quick, pained “yes,” then moved on. Really, however, that was on everyone’s mind, as portions of the performance are rendered inaudible by the actor’s frequent snorts. Unlike Leigh’s last revivification of cultural history, Topsy-Turvy (1999), which focused on a single period in the lives of Gilbert and Sullivan, Mr. Turner spans the last 26 years of the artist’s life, and without the character introductions and title cards found in most biopics you’re likely to find much of it opaque. I did latch on to a few things, like Turner’s reaction to photography, which to some extent makes his work obsolete, and how his close relationship with his father (contrasted with his tangled relations with women) influenced his art. Best perhaps to ignore the grunting and enjoy the film’s handsomely realized cinematography, production design, and music.

Mr. Turner does accumulate interest over its two and a half hours. No such luck with the 130-minute Foxcatcher, which says little beyond what a 48 Hours segment or a magazine article could about a sensational murder, and maybe even less, given a compression in chronology to shore up some questionable themes. Wheezing a Main Line accent through a putty nose in a competent display of Great Acting, Steve Carell is the eccentric John du Pont, scion of one of the world’s wealthiest families, who takes an interest in struggling wrestler Mark Schultz (Channing Tatum, looking like a shorn buffalo), an Olympic gold medal winner in 1984, and invites him to live at his lavish Pennsylvania estate. Trying to put together a world-class wrestling team to restore “American honor,” the billionaire also sets his sights on his prize catch’s more accomplished brother, trainer Dave Schultz (Mark Ruffalo), who initially balks. But money changes everything–and so do drugs and guns and some lost matches. The movie, which implies a kinky relationship between the utterly sexless du Pont and Mark in a strange wrestling/sex scene, then fakes a cause and effect between a cold streak on the mat and a killing, when in fact eight years separated the two events. Vanessa Redgrave, in three brief scenes (two of them without dialogue), plays du Pont’s disapproving mother, for which she has somehow been mentioned as a leading contender for a supporting actress Oscar. Anything’s possible: In a slow year at Cannes, director Bennett Miller won best director, for a dull, lugubrious comedown from Capote (2005) and Moneyball (2011).

Mr. Turner does accumulate interest over its two and a half hours. No such luck with the 130-minute Foxcatcher, which says little beyond what a 48 Hours segment or a magazine article could about a sensational murder, and maybe even less, given a compression in chronology to shore up some questionable themes. Wheezing a Main Line accent through a putty nose in a competent display of Great Acting, Steve Carell is the eccentric John du Pont, scion of one of the world’s wealthiest families, who takes an interest in struggling wrestler Mark Schultz (Channing Tatum, looking like a shorn buffalo), an Olympic gold medal winner in 1984, and invites him to live at his lavish Pennsylvania estate. Trying to put together a world-class wrestling team to restore “American honor,” the billionaire also sets his sights on his prize catch’s more accomplished brother, trainer Dave Schultz (Mark Ruffalo), who initially balks. But money changes everything–and so do drugs and guns and some lost matches. The movie, which implies a kinky relationship between the utterly sexless du Pont and Mark in a strange wrestling/sex scene, then fakes a cause and effect between a cold streak on the mat and a killing, when in fact eight years separated the two events. Vanessa Redgrave, in three brief scenes (two of them without dialogue), plays du Pont’s disapproving mother, for which she has somehow been mentioned as a leading contender for a supporting actress Oscar. Anything’s possible: In a slow year at Cannes, director Bennett Miller won best director, for a dull, lugubrious comedown from Capote (2005) and Moneyball (2011).

My 20th year attending the New York Film Festival was highlighted by a severe case of Whiplash, which I was happy to endure. An intoxicating mix of teacher movie, music story, and neo-noir, the film conjures for a pressured music conservatory student, jazz drummer Andrew (Miles Teller) a Mephistopheles of a conductor, Terence (J.K. Simmons). Terence, a relentless perfectionist who baits his students mercilessly, is the instructor of his nightmares–and maybe his dreams, if he can survive a barrage of criticism, delivered at drill sergeant speed. Thrillingly paced, the movie sprints past its crudities and improbabilities to a knockout showdown that puts both actors, so sharp and funny at the Q&A, into orbit. (Re: Simmons, now that is a ferocious, awards-level performance.) Expanding a short film (featuring Simmons) that played at a prior festival, first-time writer/director Damien Chazelle, a drummer drawn to the “violence” of the instrument, goes for the jugular of our complacency. “What are the two worst words in the English language?” Terence philosophizes. “‘Good job.'” At a festival that was for me full of carnage, Whiplash showcases what I best like to see–new blood.

Comments