In chronicling Electric Light Orchestra’s backstory for Mojo magazine in 2001, Jim Irvin admitted that he’d originally dismissed the band’s music as empty calories during the Sex Pistols’ heyday. “What a horrible snob I was. Of course, the dream of punk as a great proletarian force was cobblers,” he wrote. “The real ’70s Music Of The People was being made by disco acts and bands like ELO, a noble music that’s uplifting and unpretentious. You don’t have to decode it or hitch a lifestyle to it. It’s music made with pleasure, for pleasure; a rare commodity we should treasure.”

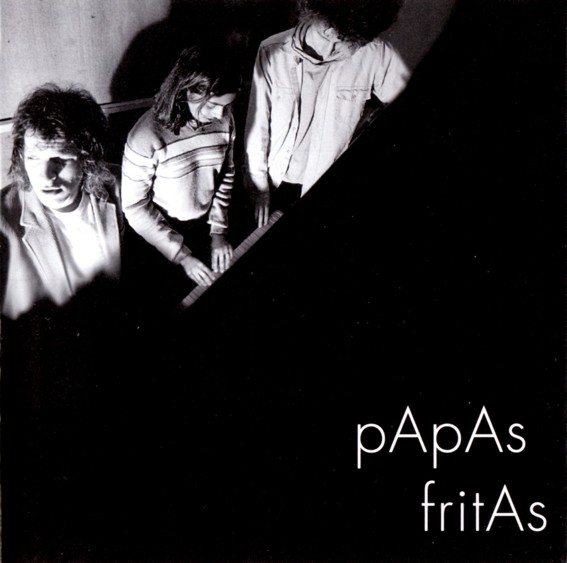

Papas Fritas’s self-titled first album was released by Minty Fresh on October 10, 1995.

French fries may be nothing more than empty calories as well, a guilty pleasure if ever there was one, but when a trio of Tufts University undergraduates named their band Papas Fritas in the early ’90s, they began to dig a tunnel out from under the mountain of flannel that had crash-landed on the indie-rock scene. Nirvana and their Pacific Northwest brethren may have slain the hair-metal dragon of the late ’80s, but at what price? Melodic hooks, for one, not to mention a sense of playful exploration within the borders of verse-chorus-verse song structure. Which is why it’s a good thing a sitar player, an architect’s son, and a Goddess arrived on the scene 20 years ago with one of the best debut albums of all time.

Just as their band’s name employs the Spanish translation of an American fast-food item with French-language origins to phonetically declare that “Pop has freed us,” the music of Shivika Asthana (drums, vocals), Keith Gendel (bass, vocals), and Tony Goddess (guitar, piano, vocals) combines various styles and signatures to remind their listeners that pop can free them too. Over the course of three albums — Papas Fritas (1995) was followed by Helioself (1997) and Buildings and Grounds (2000) — the trio delivered one memorable melody after another, heightened by charged performances, no-frills male-female harmonies, and a determination to get it right and make it count, evoking the finest qualities of Sly & the Family Stone, especially on that band’s own kaleidoscopic, freewheeling debut, A Whole New Thing (1967).

In this oral history commemorating the 20th anniversary of Papas Fritas’s self-titled first album, the three members of the band explain how it came to be.

an outtake from the 1995 photo shoot for Papas Fritas; from left, Keith Gendel, Tony Goddess, and Shivika Asthana (photo credit: Tim Leanse)

“You’ve got a lot to learn about me / You’ve got a lot to learn about / Possibilities / Probability / Prospectability”

— “Possibilities,” Papas Fritas, 1995

Keith: I was a year older than Tony and Shiv. They went to high school together. It was kind of preordained they’d be in a band together.

Shivika: We were very good friends in high school. It wasn’t planned, but we both ended up at Tufts [located in Medford and Somerville, Massachusetts, a few miles north of Boston].

Tony: Her roommate was my wife, Sam, though she and I didn’t start dating until the tail end of college.

Keith: I kind of flailed about settling on a major. I started out in engineering but didn’t really bond with the uptight vibe. I changed to premed but pretty quickly realized that it wasn’t really right for me, and I didn’t want to be pigeonholed into the next 15 years of what I was going to be studying and what my life was going to be like. I ended up graduating with a degree in biopsychology because by that time I had fulfilled most of the requirements for the major. It was the path of least resistance to the real world.

Shivika: I was there to get away from Delaware. (laughs) I majored in biopsychology.

Tony: Dover’s the state capital, but Wilmington is the most— It’s a major city. It has skyscrapers and a major port. DuPont’s there, and lots of banks and credit-card companies. It’s 30 miles from Philadelphia, and I don’t know the mileage to D.C., but we definitely grew up driving to Philadelphia or to D.C. to buy records and see concerts as soon as we turned 16.

Keith: Music was always a part of my life. My grandfather played violin in the Houston Symphony, and I started playing clarinet in sixth grade. In high school I was in marching band, just like Tony and Shiv were.

Tony: Marching band was a big thing in our school because you got to travel.

Shivika: I played the saxophone for one year, and then I took the typical teenage-girl route and started twirling a flag — they were called “the silks,” in quotes.

Tony: I played trombone. In fourth grade or whatever, they just go around to all the kids; they were like, “You have long arms — you should play trombone.” I grew up in a house with a piano, and pretty early on I discovered Rush. My dad had a guitar, but my parents actually made me take piano lessons for a year before I could get my first guitar. I guess they didn’t trust me to play my dad’s guitar yet.

the Tufts campus, with downtown Boston in the distance (photo credit: Tufts University)

Keith: I got to college, and maybe three months in I realized I was really missing playing music. I was like, “Maybe I’ll learn how to play saxophone and be in the Tufts marching band.” And my friend Geech, down the hall — we were into a lot of the same music — he was like, “You should buy a bass when you go home for Christmas break. I’ll teach you how to play it and we’ll start a band.” It sounded like a good idea — I had never thought to play a “rock” instrument until that point — so I bought a bass and he gave basic lessons.

We were into Fugazi, the Chili Peppers, the Pixies — loud, aggressive, male-adolescent, angsty music — and we were going to shows and moshing. The music we wrote and played was kind of like that. We started a band called Bedwetting.

Shivika: Growing up, I studied Indian classical music and learned sitar. The Pixies were the first band where I felt like, “Oh, this is cool!”

Keith: In the fall of ’91 we were looking for a singer. We were walking around putting up flyers, and Tony was at a bus stop. We had, maybe, Fugazi T-shirts on, and Tony had a Dinosaur Jr. T-shirt on. He was like, “Hey, you like Fugazi? You should come and check out my records.” Somehow we ended up back in his dorm room, and he had this amazing collection of seven-inches and vinyl. He had more records than I’d ever seen one person owning in my life.

Tony: I came up to school with about two boxes of records, but that was still probably a lot.

Something happened when I got up there; I was just starting to realize that I liked it all. Before college I basically didn’t like anything that was on MTV or that was on the radio — it wasn’t “my” music, it was mainstream, and therefore I didn’t like it. And then I just started finding the strange stuff that was mainstream — you know, even though it’s popular, it doesn’t mean that it’s not creative or unique. I let those guards down and then just got into it all, and Boston was such a record town. Still is.

I still have some of the price tags on those records, and I’ll be flipping through, like, “Man, I got that Brian Eno record for ninety-nine cents? I got that McCoy Tyner record for a dollar ninety-nine?” I guess CDs were still so on the ascendant in 1991 that records were, compared to now, undervalued.

Keith: We were always going over there and hanging out with Tony and his friends.

Tony: I used to almost resent Keith because Keith was me in high school: He would just come and borrow 10, 20 CDs or records. He would record so much music off me, and it would be like, “Keith, you’ve gotta turn me onto something, dude. Go out and buy a record and play it for me and blow my mind.” I had a bit of a hang-up about that. But when we came to be in a band together, I already knew that his taste was all right because I had taught him everything he knew. (laughs) Sam is pointing and laughing at me.

Keith: They were a really cool group, Tony and Shiv and the friends they’d made the first months of school. From that point on, I always hung out with people in the class below mine much more than I did with the people in my own class.

“Maybe, we’ll try something new / Twenty, twenty more reasons to swoon / And gently, there’s plenty of room / It’s something you won’t ever lose”

— “Guys Don’t Lie,” Papas Fritas, 1995

Keith: Papas Fritas sort of started when Geech — Mat Kessler is his real name, by the way — went abroad for a semester, to Spain. While he was gone, Bedwetting was basically broken up. We all had a mutual friend named Derek Smith, who had a basement where we could get together and play. I would hang out with Tony there a lot and play music.

Shivika: There was a hodgepodge of drums set up, and people had amps, and they would bring their instruments. You know, just something we would do for fun on a Friday night. We wouldn’t go to frat parties; instead, we would go in the basement and play music. There was one night when Tony and Keith were supposed to play a show. The drummer they were playing with, Derek, broke his elbow, and they were like, “Bummer, we can’t play the show.”

Keith: If I remember correctly, me and Tony had been playing with Derek pretty regularly, and it was more of a surf-punk, Birthday Party-type thing.

Shivika Asthana behind the drum kit in Derek Smith’s basement in 1992 (photo credit: Keith Gendel)

Shivika: I was like, “Well, there’s a drum set here. Let me try to play the drums.” The only thing I remember about that drum set is that the cymbal was hanging from the ceiling. There was a rope, and it was hanging from the ceiling somehow.

The only reason I started singing behind the drums is because I sing a lot of the songs on the albums, though on the first album I didn’t sing a ton. The only thing I think it probably did was change my stage presence a little bit, because my playing had to be okay with wherever the mike was — my arms weren’t flailing. But with my personality, I wasn’t going to be, like, rocking out on the drums. My stage presence has always been a little reserved.

Keith: The first show was in December ’92.

Shivika: I played the show, and it went well.

Keith: There were a lot of people in our scene that were music snobs and music nerds, and a lot of them were DJs at WMFO, the Tufts radio station. Tony would always be the first person to praise bands that were kind of shunned, like the Beach Boys or Fleetwood Mac — bands that I might have loved when I was a little kid, but I just never really gave them a second look because, you know, “That’s what I liked when I was a kid. I’m not allowed to like that anymore.” And he’d be like, “Hey, the Beach Boys are amazing!” Then, two months later, the entire scene’s listening to Brian Wilson and Smile, and everybody’s a Lindsey Buckingham fan. Tony was always an early adopter.

Tony: Initially, I just wanted to make weird sounds, just fucked-up stuff, because that’s what I listened to. But when you’re young, your influences are changing so much. I got a four-track because of Sebadoh and Ween and Pavement, but then I would read about the Beatles and the Beach Boys and Phil Spector making their records on four-track, and, well, “I gotta listen to those records a little more closely.” You just assume everyone had 24 tracks back then.

Keith: We recorded three albums, using a Tascam four-track that used standard cassettes, in two or three months.

Tony: The two songs on the first album that existed already were “Wild Life” and “Smash This World,” but totally different versions. They were on cassettes that we sold at shows and gave to friends. [The first cassette the band recorded in 1993 was titled “Retards/Cowboys” and contained six tracks, including “Here She Comes,” released by Double Agent Records on a four-band split seven-inch in 1995, and “Means,” which found a new home on Papas Fritas’s Passion Play EP that same year. Two other songs from that EP, “Howl” and “Radio Days,” originally appeared on the band’s second cassette, “Careers for Culture Lovers” (seven tracks), as did “Wild Life,” while a third, untitled cassette (eight tracks) featured three songs that Papas Fritas used to create their first seven-inch single, Friday Night (1994): the title track, “Angel,” and “Smash This World.” The rarest of Papas Fritas rarities, none of the three cassettes appears to have made its way onto the Internet in the form of bootlegged MP3s as of this writing. —Ed.]

Keith: I love those songs. They’re so raw and original. The very first tape, if it’d actually been released, if we’d put it out there, I think it would’ve made an impression on the lo-fi scene that was happening at the time.

Tony: I was 18 years old. The songwriting, if you want to call it that, was not as influenced by the classics [as on Papas Fritas] so that we would seem a little more original. The lyrics were an afterthought; it was just “How silly and ‘inside joke’ can we be?”

Keith: The first tape totally had a lot of amateur stuff going on, but it had really great energy, I thought — explosive energy, but not aggressive. Tony was full of ideas, and he was just throwing it all out there, all against the wall, but it was really fun. I liked the speed of it.

Tony: This label called Half a Cow, out of Australia, wanted to put out those cassettes, but we’d just signed a record deal [with Minty Fresh] and we didn’t want to piss them off. I guess we thought that we had something to say and that those recordings were so juvenile or something that they weren’t really songs. [Half a Cow, run by onetime Lemonheads bassist Nic Dalton, eventually licensed the band’s final album, Buildings and Grounds, for release in Australia. —Ed.]

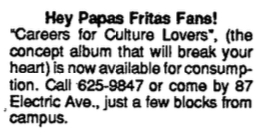

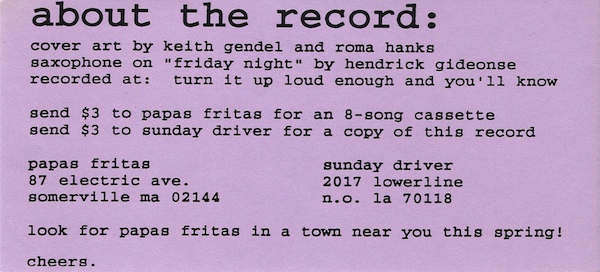

a classified ad from the November 15, 1993, edition of The Tufts Daily

Keith: The three cassettes came out, literally, in three months. It was insane how fast songs were written and put to tape at that point. When it came time to record our first LP for Minty Fresh, the process evolved into something very different — much slower and more thought-out. All of a sudden Tony was spending hours and hours rewriting and arranging and rearranging and reworking and really being detail oriented and very meticulous. That was pretty different from the earlier stuff, where it was almost like a sketchbook. Not that he wasn’t paying attention to details and putting thought into the early stuff too, but there was a real shift, I think, when he got into Lindsey Buckingham and Brian Wilson and was coming up with a philosophy of a sound and trying to define himself.

Tony: I was just so sick of indie rock, man. If I heard another song that didn’t have the title in the lyrics … I’m not quite as up in arms now, but at the time I was like, “Enough. I want a self-titled album with a bunch of two-and-a-half-minute songs that get to their point and aspire to the sonics of Nilsson Schmilsson.” That record was big for me back then too. I really was obsessed with having that tight drum sound, and we wound up getting our own version.

Shivika: Tony had a drum set too. He plays everything — he can play everything. So what he would do is, if he knew he wanted to hear a song in a different style, he would just do it on his own and play the part that he heard in his head. He’s not going to be playing a ton of drum fills, but he can hold the beat, so he would play the beat that he would envision for that style and then dub all of his stuff over [the original take] just to get a sense of how it would feel. He would do that on his own, and then we would record a new version and I would play the drum part [Tony had come up with], but in a modified way, the way I would play it.

Tony: You recorded Shiv’s drums and then kind of painted around it until you came up with what you thought was the right way to do it, and then sometimes you were like, “Actually, but now I want a longer intro” or “I want to restructure the song,” so you would start again. But I was never like, “I want to play all the instruments and be Mr. Man.”

I run a recording studio now [Bang-a-Song, in Gloucester, Massachusetts], so I’m recording bands all the time, and we talk about whether to record to a click track or not. And just because you record to a click track does not mean your record’s going to sound like a machine. But bands want the drummer to play, then they want you to sound-replace his drums, and they want you to Auto-Tune their vocals. They think it’s all about achieving this kind of mechanized perfection, this kind of airbrushed thing. But it’s like, “Man, you guys listened to Led Zeppelin. Listen to how imperfect that is — shit’s out of tune, you can hear the bass drum squeaking. Listen to Neil Young, man. You’re telling me you would Auto-Tune Neil Young?” I worry about the younger generation. (laughs)

Shivika Asthana recording a vocal in 1995 in the basement of 87 Electric Ave., otherwise known as Hi-Tech City, Papas Fritas’s studio (photo credit: Keith Gendel)

Shivika: There are some songs where he would have a lot of the structure, or he’d have the parts and we’d structure it together. I think that’s one reason why Tony and I are very complementary: He has a lot of training — I mean, of course he’s got a lot of natural talent as well — but he has that analytical side where he can understand why certain things are working together and why they’re not. But, for me, it’s literally whether I can hear it or not — if it sounds right or not.

Tony: I think Shiv always knew that she was kind of fresh as a drummer, in that she enjoyed coming up with a little part here and there that was a hook. It wasn’t like, “I’m a drummer who studied drums, and this is how you play the drums.” It was like, “What would be an interesting thing to add to make it feel creative?”

Shivika: He would overdub stuff, and he did a lot of finagling on his own. We wouldn’t sit there and play the same thing five different ways. By the time that I came along, in terms of my parts to record, we were just doing full takes, so we had to be good.

Keith: If I remember correctly, Tony was a music major, and he convinced the music department to let him work on the album and the band as an independent project. He kind of graduated early and was working full-time on the album while Shiv was in school and I was working full-time.

Tony: Keith lived in the same house, and I always wished he was a little more involved, but I knew where Shiv was coming from — I didn’t expect her to want to, like, learn how to record a vocal in “omni” instead of “cardioid” on the microphone. Shiv wanted to show up and practice for an hour and record drums for an hour and then go home. And that was fine.

Shivika: I sang a lot of classical Indian music when I was little, so I definitely had a sense of pitch and tune and all that, but I never sang sang. And, I mean, to this day I don’t really think of myself as a singer. I sing like I talk.

A lot of those ba-ba-ba [harmonies] were just things I heard in my head. I can’t write music. I don’t play piano. I can play guitar, but I don’t know how to write from scratch. But if I have a snippet, then I can totally add a melody with no problem, so that’s kind of how we collaborated.

Keith: Tony was obsessed with finding the essence of each song. It was really about stripping them down to layers of minimal elements. There’s an early, live version of “Guys Don’t Lie” where the bass and the guitar play the same rhythm. It was very chunky. (imitates the sound) And it’s really cool that he was able to extract the bass and have it chug on quarter notes. I’m not describing this very well. (laughs) But he broke it down to its essential elements, is what I’m trying to say.

Keith: I’m guessing that must have been Fleetwood Mac inspired, that particular arrangement [“Guys Don’t Lie”]. I know that [the arrangement of] “Lame to Be” was inspired by Steely Dan.

“Lame to Be” is another example where the guitar and the bass were playing the same thing, but he separated out the rhythms and layered them. Tony was really thinking about music in a spatial way at that point.

Tony: What finally happened was, I struggled with “Lame to Be” [for the seven-inch version of the Passion Play single], trying to figure out how to make it, I don’t know, just more interesting, and finally had gotten to something that was shaping up like how it turned out on the album, but it was like, “All right, let’s just let it be. We’ll record a good version for now of how we do it live.” I think maybe with “Passion Play” in the can, and feeling so confident about it, that it was okay for “Lame to Be” to be a document of what we sounded like live, knowing that we would do what I thought was a cooler arrangement on the album later in the year. But trying to get “Lame to Be” from the 45 version to the album version was the whole learning process that I’ve been on ever since.

Tony: “Passion Play” was written as kind of a fake blues song. Our friend Tom Swafford, who did the string arrangement, he was a music friend at school, and I said, “Hey, man, I want you to write some strings. What song do you want to do strings for?” He picked that one, and we brainstormed about sustained whole notes for the verses and then some kind of rippling arpeggio for the chorus and then something that pushes the key out and back in on the breakdown. He wrote it all after we did that.

Shivika: We recorded the strings for “Passion Play” in the Tufts football team’s showers.

Tony: That was the first time we tried recording the strings, on four-track cassette. That whole version of the song was scrapped, but I did record the vocal for “High School, Maybe” [a B-side that can be found on the 2003 compilation Pop Has Freed Us] in those showers at some point. I think “Lame to Be” was going to be the A-side of the single and “Passion Play” would be the B-side, but with the strings it just turned out so cool it was like, “No, that’s the A-side.”

We were just starting to learn how to arrange and break up what you’re doing on your instrument into parts, as opposed to just— You know, a lot of people, they write the song and that’s how they play it. They don’t know how to play it on a different instrument or play it in a different register. I was just learning how to do that, but “Passion Play” already had so much more going for it.

Tom Swafford (center), who created the string arrangement for “Passion Play,” recording an early version of the song in 1993 with Tony Goddess (left) in the Tufts football team’s showers (photo credit: Keith Gendel)

“I still can’t breathe, but I feel okay”

— “Holiday,” Papas Fritas, 1995

Tony: In high school I was so not even a songwriter. Papas Fritas started our sophomore year of college, and we had our record deal by the senior year, so I guess some of those songs [from the first album] were started before we had a record deal, but it was all kind of within Papas Fritas starting, which was essentially me beginning to try and write songs, just wanting to learn the whole thing.

Shivika: The first album, Tony was pretty much writing the lyrics and melodies and everything, and I was embellishing — you know, just adding little harmonies or whatever. Later, I started writing more lyrics, and a lot of times he would have the hook for certain songs — he would have the main chorus lyric written out — and then I would help with the rest. Or, songs that I sang on our later albums, I would write all the lyrics for. Like, starting from “Say Goodbye” [from Helioself] — that was my first attempt at writing lyrics, and from there I just started doing it more and more. But I don’t feel like it’s my strong suit.

Keith: “My Revolution” was the first song I’d written where I came up with all the parts and the lyrics and the melody and everything. You know, you’re on a record label and you’re doing real tours — I was like, “I should probably be a little more serious about this and see how far I can go with it.”

Tony: I’m sure you’ve read this with other songwriters: You’re just spitting words to come up with something. You aren’t writing “lyrics.” But then, half the time, that first line sticks. I mean, when I wrote “Holiday” I’m sure I just picked up the guitar and went (sings) “Take one of these on your holiday …” And it was like, “All right, what’s that about?” and I just filled it in from there.

I like saying simple things in, hopefully, poetic ways, but lyrics are my Achilles’ heel, man. I’m so much more about the feeling of the record and the notes than the actual words.

Shivika: I respond to different styles more than others. It just depends on what I respond to viscerally. That poppy, bouncy feel just feels better to me than not, or that strummy feel feels better to me than not. And even the kind of key and the pitch and the tone— I don’t even know what you call it, really, but there are some songs, when Tony would play them I would instantly be like, “I don’t like it.” (laughs) But that’s just my personal preference. I’m trying to think of a song that I just did not like. Oh, I know — “I Believe in Fate” [from Buildings and Grounds]. I never really got that song. There’s something about the notes and how they work together that never quite— But out of all the songs we ever played, there were probably only two that I was like, “That doesn’t work for me.”

Tony: Shiv had really strong opinions. She doesn’t like rock music, so anything that sounded like the Rolling Stones, she wouldn’t want anything to do with.

Shivika: But then there are songs like “We’ve Got All Night” [from Helioself] where I’m like, “Oh, man, that feels so good.” I can’t explain why, but there are just certain songs that I react to. I’m sure there’s some scientific reason, but I don’t know what it is.

Because of the fact that I’m not trained and my range is pretty limited, I think that’s why Tony would cater the melodic range to where my voice sounded the best. There are songs where I reach and I stretch, and that’s good for me in general as a person to see how I can do that — you know, like “Sing About Me” [from Helioself], where I’m kind of screaming? — but, personally, that’s not where I feel like my voice sounds the best, so he would write arrangements that worked for my voice.

Keith: Tony had quite a reputation at that point in our house, in the community, because the word was getting out that he was in the basement for— I don’t know exactly, but we all imagined it was 15 hours a day. But who knows, it might have been more. He’d crawl up from the basement, his eyes all glazed over, his hair all frazzled, and with some really cool arrangement that he was working on. There was a lot of talk of him being either crazy or a genius or someplace in between.

We lived in a classic Somerville three-story duplex. The apartment downstairs had three people. Tony lived downstairs, above the studio, which was in the basement, and then upstairs there were five people. I lived in that house for probably three or four years; I changed rooms twice, and Tony changed rooms two or three times. Almost everybody in the house was in a band. There were probably four or five different bands that were represented, and there was always someone playing in the basement practice space. It was a really neat little community.

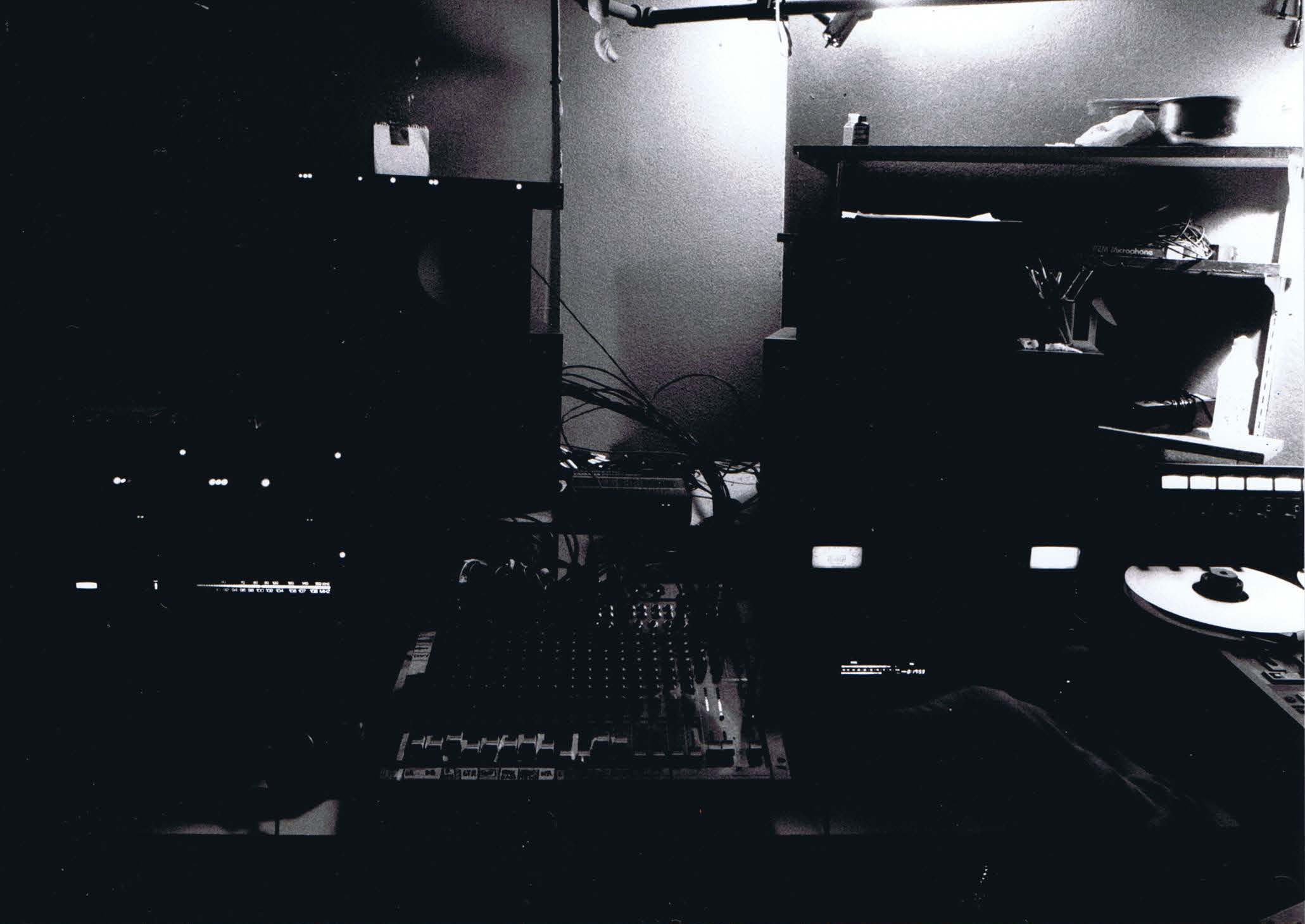

When we signed to Minty Fresh, they gave us some money and we bought an eight-track, a Mackie mixing board, and NS-10 speakers, and carved out that little practice space in a corner of the basement. The mixing room was like a panhandle off the practice space — probably five feet wide by ten feet deep, and all the equipment was along the wall. It was like being in a hallway, definitely breaking all the rules for how to set up speakers and get accurate sound representation.

Tony: The landlord was actually cool enough to help us construct the walls of the practice space, which is kind of incredible. I remember getting particleboard — pretty minimal soundproofing. It was small. It was really small.

Shivika: I would say “studio” in quotes. (laughs) Now Tony has a studio, but back then …

Keith: Someone was giving away a piano, and I don’t remember if it was in the trash or Tony saw it in a want ad, but he built a sound booth around it with carpeted walls in the living room of the downstairs apartment. He also put tacks on all the hammers, so it was a tack piano — that’s why it has a kind of percussive, tinkly sound to it on the album. I have this really strong memory of this, like, room inside the living room taking up the entire room. I’d come downstairs, like, “Wow, these people have no living room anymore.”

Tony Goddess playing piano in the downstairs apartment at 87 Electric Ave. in 1995 (photo credit: Keith Gendel)

Tony: “My Own Girlfriend” might’ve been the first song arrangement we did where there’s an element that plays one note the whole time. I think it’s an upright piano we had, and we held a T-shirt against the string to make it sound more percussive. In the final mix one of the eight faders just had that constant “ping” on it, and we rode the fader, bringing it in and out of audibility.

I’m sure I wrote it in 20 minutes. I didn’t think we’d put it on a record because it was so short, but Keith advocated for it, and I’m glad he did. The vocal wound up too high for me to comfortably sing, so I did the falsetto and chest an octave below. I think J Mascis did that a lot on Dinosaur Jr. records — that gave me the idea.

Shivika: Tony’s definitely a perfectionist, and I’m not. But I respected the fact that he wanted it to sound the way he wanted. I didn’t really question that.

Tony: In those early days it was fun to just explore and record and erase and start over from scratch, so I would do that a lot.

Keith: That kind of drove me crazy, when we would have a song — you know, “This is a perfectly good song” — and then Tony would say, “No, I can make it better,” and he would spend hours rearranging it and coming up with new ways of doing it. I was like, “The old one was good. Why don’t we just write another song?” But we were different. I’m kind of lazy and not as detail oriented as he is — and never will be. (laughs) I guess I’m more of a big-picture guy.

Tony: It did take a lot of time and energy to try and come up with our sound and poke around in the dark until you figured out a way to do it that you think feels fresh and feels like your unique expression, so I guess sometimes I would get a little disappointed that Keith or Shiv would say, “Oh, sorry, I gotta study for this exam” or “I’ve got Frisbee-golf practice.” You mean to tell me this isn’t the most important thing in your life like it is in mine? (laughs) Once you start making records, you realize how hard it is and how it doesn’t just come out like that when four guys get in a room and play music.

the Hi-Tech City mixing room (photo credit: Keith Gendel)

Keith: When I listen back to it now, I find it the most moving of our records. It’s the sound of discovery and fearlessness.

Tony: There aren’t many bands that sound like that first album. The guy who mastered it, Roger Siebel, who was a guy who’d been doing it for a long time, said, “I don’t know if I’ve ever heard a snare drum sound like that before.” I remember being so proud of that.

Shivika: I would probably say the first album is my favorite because it sounded so much cleaner than I expected it to, but still underproduced. I just think it sounds very authentic. Tony got more into producing and more into layering later on, and I think there’s value in that too — Buildings and Grounds sounds much more polished — but I really liked the way that first album sounded.

Tony: Your limitations are your strengths. Your lack of knowledge makes it cooler than if you knew what you were doing. That was our justification a lot of the time — it was like, “Well, it’s never going to be as good as an Al Green record, it’s going to be our own fucked-up version of it, so we might as well not worry about it. It’s still going to be me singing, so let’s just do it.” The whole notion of you don’t rip off one or two bands, you rip off a hundred and it’ll turn out all right.

“Something special in the end / Said the dotted line to the fountain pen / Just stay on course, stay in tune, and wait in line / In the basement, lost track of time”

— “Afterall” (Papas Fritas, 1995)

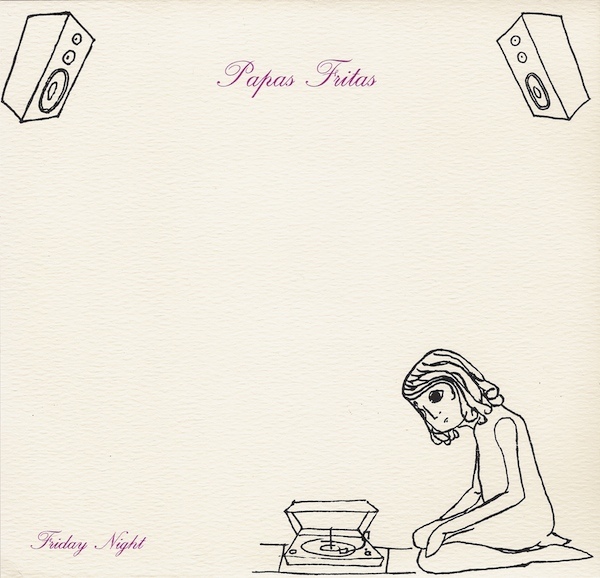

Tony: I started the band being in thrall to the Replacements and Pavement. We got signed because of that single version of “Smash This World” [on the Friday Night seven-inch released by Matt Hanks’s Sunday Driver label], and by the time we were able to make our first album, that’s what the record company wanted — more guitar indie rock.

Keith: Minty Fresh was a pretty tiny label when we signed to them. Jim Powers was a former executive with BMG; he had signed the Cowboy Junkies, so he had been a pretty big A&R guy and had a lot of connections. He was like, “I’m taking this label really seriously. This is not a little boutique-y, indie thing. I’ve got big plans.” They’d released maybe five seven-inches, all by bands we’d never heard of except for Liz Phair. Then there was a band called Veruca Salt, who had a song called “Seether,” and it became a hit single out of nowhere.

That was while we were recording the album. We found out it was going to be released in the United States with full distribution, and in England, France, Germany, Belgium, Sweden, Spain — basically, western Europe — and Japan. So Jim had all these deals lined up before the record was even finished. That could be another reason why all of a sudden Tony was working 15-hour days on it. He might have become a little bit more obsessive at that point because of the pressure.

Tony: “Afterall” was the, quote, unquote, single off the album that they tried to push, and we did a video for it. They wanted more of that. Not to be dismissive — they weren’t jerks, or wrong or anything. I totally understand where they were coming from. People thought bands like Pavement were going to be really popular. You know, more poppy and tuneful than grunge had been, but still with that grungy sound.

Keith: I remember thinking “Afterall” was really cheesy when I first saw it, but now, looking back, it’s my favorite of our videos by far. Paul Sanni [the engineer on Papas Fritas] and a few of his friends made it, using old-style video effects.

Shivika: We’re performers in one sense, but then we’re so not in another. I’ve performed a lot in my life — onstage I did a lot of Indian dance when I was little — but I hate being on camera. I’m conscious of it, I don’t seem relaxed or natural, but the “Afterall” shoot was fun because we were just being goofy and funny, and we were with our friends. It didn’t really feel like somebody was filming us.

I remember us doing a TV show in France [in 2000] called Nulle part ailleurs. It was a live variety show, and if you ever find that online, we’re all stone-faced. All of our French friends who were watching and were superpsyched that we’d gotten this gig, they were like, “Oh my god, Shiv, smile — just smile!” I was so tense it was ridiculous. That was definitely not the case for “Afterall.”

Tony: I was probably nervous for a second and then decided to chuck that feeling and let it fly, and that’s why I’m pretty hammy in the video. I just remember having fun.

Tony: It was shot in a warehouse in a town called Haverhill. Paul Sanni and his friends all went to Bard College; they were really cool, creative guys, a few years older than us. We had met through the Tufts radio station — I think Paul was handling some of the sound when they’d have live bands — but he and his friends also did video. So they did “Afterall,” and they did the “Way You Walk” video [in 2000], and he’s now a producer at WGBH, Boston’s big public-TV station. [“Hey Hey You Say,” the second of Papas Fritas’s three music videos, was helmed by Mike Mills, the writer-director of Beginners, for which Christopher Plummer won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor in 2012. —Ed.]

Do you know the term voicings? There are 12 notes, and then the chord usually starts with 2 to 3 notes, maybe 4, maybe 5. But certain voicings and certain chords, you play them and they instantly are the Replacements. So “Afterall” is instantly the Replacements because I’m using that chord and that voicing, and it means that there’s a ninth in it, basically. It wasn’t designed to be the last song on the record, but having it last conveyed this idea, I suppose, of putting all these different styles on the record, and then at the end it’s back to the original sound that we had.

Shivika: We all have very distinct personalities. I think that’s what made us an interesting band to watch. That’s what you got from the shows that you wouldn’t probably get from the albums.

Tony is a showman, and he had this idea of what being onstage and playing in a band— His idea was very different from mine because he’d studied music and loved music and was immersed in music in such an intense way from such a young age. I think he had a lot of, you know, things to refer to, and so he would try them. He would throw his guitar over his back, and he would do all this other stuff, and I had none of that context, so I was just like, “Okay, I’m here playing the drums. I’m smiling. I’m looking. I’m not doing anything that I wouldn’t normally do if I was walking down the street.”

Tony: I remember going to Sam Goody’s at the mall, and I don’t know if they were all like this, but Sam Goody’s also sold guitars and sheet music, and a guy — I mean, I’m sure he was a teenager, but much older than me — was playing “Fly by Night” by Rush on guitar, and I was like, “I didn’t know that human beings could do that.” I just thought that wizards in scientific castles made that music. I mean, summer camp, everyone was talking about how heavy this band AC/DC was: “The guitarist doesn’t even play the strings! He just turns the knobs to make crazy sounds!” You know, how filled with myth and majesty that music, particularly metal, is for preteens. So yeah, I was totally one of those kids playing trombone, in love with Rush.

Shivika: And then Keith was right in the middle. He had a little more context, but he also was a kind of reserved, shy guy. You look at all of us, physically, and we’re all so different that I think people just thought it was a really enjoyable thing to see. And when we played, we all loved playing the songs, so that would come out. It was just a very natural, positive vibe. That’s what we tried to give off — like, “We are psyched to be doing this.” Even when we were not.

Tony: “Wild Life” was always one that we opened with. Not to sound too technical, but “Wild Life,” we’d pump [the note] A the whole time. I actually learned this from Cheap Trick, where you open with a song [“Hello There,” in Cheap Trick’s case] where one instrument is introduced after another and you can groove on it for a while without losing any energy, just building the tension, so that the soundman — because we didn’t travel with our own soundman, at least in the States — can get it together. If you come out and try and do your most ambitious song right away and the soundman’s not on his game, he could totally take the wind out of your sails, so it always seemed smarter to open with one that you knew would get over.

Tony: Now that I’m playing in, like, bar-gig bands and being more of a three-sets-a-night-type musician, where you’re playing covers and you’re playing a bar where everyone just wants to be picking up each other, there’s this real tendency to not play ballads — like, “You’re gonna lose the crowd, man, don’t do it!” But I guess when you’re in your own indie-rock, original band, people are coming to see you, so you feel more confident doing that. We would definitely play two ballads, at least, every night [“Explain” and “TV Movies” on the Papas Fritas tour]. We were confident in our ballad playing.

Shivika: “Explain” was my favorite to sing live. I also loved singing “Guys Don’t Lie.” And “TV Movies.” You know, those slow, softer songs — I gravitate more toward those.

Tony: “TV Movies” was used in an ad for Luxottica eyeglasses that aired during the Super Bowl in ’96. We were good friends with a band called Ditch Croaker that wound up making one record on Reprise [Secrets of the Mule, 1996]. They were a total indie band for years, like us, and we spent a lot of time tossing gigs back and forth. The drummer, Tim Barnes, worked at a video editing house, and he had put “TV Movies” into the ad [as a temp track] — that’s how that happened. We’d graduated from college, and Shivika said, “We’ll give it a year to see if we’re making a living.” And with that TV commercial, we eliminated our debt to the label and we each made four thousand bucks. We were like, “Four thousand bucks? Sure! That’s a living! We’ll give it another year.”

Keith: My last class at Tufts was in April or May of ’94. I think the week I graduated was the week we got the call from Minty Fresh, when they called Tony and said they wanted to sign us. So I never really had that awkward period after college where I didn’t know what I was going to do. Immediately, this interesting thing was happening to me, and all of these possibilities were being formulated.

I was working at a lab at Harvard, studying animal models of addiction in rats and pigeons. I had that job the entire year until Tony and Shiv graduated, because we couldn’t go on a full tour until then. I went in to my boss and said, “Okay, I’m quitting my day job. My band is going on tour.” I’m pretty sure he saw it coming, because I was growing more and more unhappy working with lab animals and starting to get some serious attitude about it. I just didn’t understand why the animals had to live in little cages for the benefit of humans — why are we so special? (laughs) But my boss was from Berkeley and very sympathetic to the rock ‘n’ roll dream.

We just got licensed in Japan and Australia (Polystar and Shock). Best Buy and Borders have picked up copies for their chain stores. We got reviews in Details, Interview, Time Out, CMJ, and The Tufts Daily. There’s a big buzz about us in Sacramento, so Tower Records has us on listening stations for free. Jim Powers said he’s hoping we sell between 10,000 and 30,000 records.

Last night we played St. Louis once again … our 5th show at Cicero’s? We played on a pretty quiet night w/ Chris Knox and SF Seals. My parents were in town, so the whole family got to hang out and drink beer together again. We made $100 from the door and another $80 from merchandise, so all of a sudden we have money again. We’ve been kinda low since the NW [October 6 in Portland, October 7 in Seattle].

— Keith’s tour journal, October 17, 1995

Keith: Tony got arrested for stealing a piece of candy in a grocery store in Memphis.

Tony: It was at a Piggly Wiggly, if I’m not mistaken.

Keith: He ate a lollipop, and he was finished with it by the time we were checking out. The manager came up and asked us if there was anything we were missing, and we had no idea what he was talking about.

Tony: We were checking out, and the manager goes, “Hey, you gonna pay for that lollipop you ate?” I was like, “Oh, I totally forgot. Here’s 25 cents,” and the guy says, “No. Officer, this man was shoplifting.”

Keith: The manager called the cops, and he spent the night in jail.

Tony: It was so upsetting because I was still booking the band, and I had booked us all the way across to California and back, spent all this time and energy, and then I went and got arrested. When they’re checking you in [at the jail], they’re like, “Oh yeah, you’re going to have to stick around and go to court in a couple weeks,” and I was just beside myself. It was a ridiculous— I was a rude kid, I shouldn’t have done that. But the police officer was even objecting to the store manager, saying, “C’mon, man, you’re gonna take me off of the job to bring this kid in for this?”

Shivika: I was scared for him, but Tony seemed so easygoing and happy-go-lucky about it. He seemed so calm, but I remember being very tense about it. I think he just didn’t want us to get too freaked out, but I was already freaked out, and I think he knew because of my personality.

Tony: I spent the night in the drunk tank. It was a Saturday night in Memphis [September 16, 1995]. People were in there covered in blood, people were in there vomiting into their shoes. We all had to take a shower the next day, but somehow — we were all naked — some guy had gotten a joint in there. I didn’t smoke the joint. (laughs)

Keith: We had plans to go see Al Green preach and sing at his church the next morning. We had to go bail Tony out instead.

Tony: I was in court the next day, and the judge said that I had paid for my crimes, that my night in jail was enough of a comeuppance.

the cover of Papas Fritas’s first single, Friday Night, released by Sunday Driver in 1994

We hadn’t even played in Memphis that [Saturday] night — we had played in Arkansas. Our best buddy, Matt Hanks, who Shiv and I grew up with and then he put out our first 45, he lived in Memphis. On the east coast we used Delaware as a bit of a home base, and in the south I suppose you’d say we used Memphis. And Keith’s sister went to Washington University, in St. Louis, so things were always kind of based around hitting those spots.

Keith: The funny thing is, if you look at our tour dates before 1995, we never make it farther than New Orleans or St. Louis, and that’s because we were going on tour during spring break or Christmas break. We only had, like, a week off from school, so we could never go farther than a three- or four-day drive away from Boston. A lot of shows were weekend trips, like to New York City.

Shivika: I didn’t even tell my parents that I was going on tour the first time.

Tony: Shiv told her folks that she was going to Sam’s house for spring break when we did our first tour [in March ’94, to promote Friday Night].

Shivika: I think they would’ve taken issue with me driving in a van with two guys from Boston to New Orleans during spring break, even though they knew Tony well. They knew I was playing music, but I don’t think they knew it was so serious, that that’s what I was going to be doing after college. But in ’94 I don’t even think we really had that in our minds. So, for me, it was just this thing that I didn’t feel like getting into with my parents. I was like, “I’m gonna go to Sam’s,” and then we went on tour.

the insert for the Friday Night seven-inch single, which included drawings by Keith Gendel, who created the majority of the cover art for Papas Fritas’s albums, singles, and self-distributed cassettes (image credit: Discogs.com)

I thought I’d write a little about the status of our LP … you know, for posterity. The official release date (to stores) was yesterday, 10/10/1995. 4000 CDs were made in the 1st pressing — 1000 for free goods (press, radio, etc.) — and 1000 vinyl were also pressed. Radio promotion is being handled by Chuck and Dave at The Want Ads — they are totally spunky and very aggressive, they do a great job (I think) at sticking in Music Directors’ minds. Our press is worked by Nasty Little Man in New York City, and we’re happy w/ their job so far too. It’s been fun seeing our faces in various papers in random cities across the country. Also, we just found out that we are going to be in SPIN magazine’s top ten list for 1995 (of albums that you didn’t hear).

The album has been licensed to Pinnacle in Europe. A single is going to be released first — “Afterall,” “Wild Life” and “High School, Maybe.” Tony is going to go over to do a press tour. The full-length will be released in January and we will tour (!) in February.

— Keith’s tour journal, October 11, 1995

Tony: It was at the beginning of the Internet era, or at least the web-page era, and Shiv and Keith were hip to that early on, so we would come off tour and they’d be making real money doing web design for people, and I would be in the basement trying to make up new songs and make new recordings. There was no sense that we were going to make money from doing that. I wasn’t concerned about money — I guess my parents were a little concerned about money — but I just started to notice, “Wow, these guys are making $25 an hour doing this thing?” I worked at a record store between tours for $6.75 an hour, I think.

Shivika: This company called Aquent was training people to learn HTML and then throwing them out into the world to these companies that needed to hire web developers. I did this two-week training session at a foreign-languages school up in Newton.

Keith: I learned HTML to do a website for the band sometime in 1995. This was super, super early in the Internet days, and it had a crazy URL that had, like, 30 characters in it, and a Harvard address because I was on Harvard’s server when I was working there and I was like, “Okay, I’ll teach myself how to do websites.” I’ve always been a programmer. That was part of my job at the rat and pigeon lab in the psychology department at Harvard: I wrote programs that controlled little cups that delivered alcohol to rats and got them drunk.

The website that’s online is actually the second version: it says on the home page the year that it was fully operational. [“Version 5.34×2 created by InfinityPlusOne, and fully operational since 10.06.96.” —Ed.] I challenge you to find another website that old [that still has its original layout]; it might be one of the oldest websites out there. I’m actually very proud of the fact that it hasn’t changed. It’s like an historic building.

“So I caught another foreign movie, filmed in my hometown / Drank a lot of coffee and smoked a couple cigarettes and hopped on the inbound”

— “Wild Life,” Papas Fritas, 1995

concertgoers waiting to meet Papas Fritas after their show at Club Quattro in Osaka, Japan, on August 30, 1995 (photo credit: Keith Gendel)

Tony: In Japan we were on a really cool label called Trattoria [an imprint of Polystar]. That was Cornelius’s label. He had some records on Matador in the States at one point. Just a really out-there Japanese artist who was a superstar in Japan at the time, so anything he touched, it meant that 10,000 people were automatically going to buy the record. It was good for us pretty much right away.

Keith: There’s a book [Matt O’Keefe’s You Think You Hear, 2001]. The roadie from our tour with the Cardigans in ’97 ended up writing a book inspired by the antics. I’m totally terrified to go back and read it; I haven’t looked at it in 15 years. I always assumed that there’s tons of stuff that’s fictionalized, and my greatest fear is there’s a lot that’s not.

Shivika: I remember reading it and thinking, “Wow, that’s pretty honest. I have to own up to it.” (laughs) [According to a message posted on the band’s website on April 15, 2001, “If you decide to read it, remember that in reality, Papas Fritas are mentally stable and considerate individuals.” —Ed.]

Tony: The Cardigans asked us to tour Japan with them. We would’ve played Budokan, but Polystar wouldn’t give us tour support because they felt like it would’ve destroyed their marketing of us. The Cardigans — it’s hard to believe now — were essentially Mariah Carey in Japan. “It would be like if you opened for Mariah Carey in the United States. No one would get it, and then your fan base would be alienated because you’re opening for Mariah Carey. And it’s doubtful you would win over too many Mariah Carey fans.” (laughs)

Now no one would care if you opened for Mariah Carey. It’d just be like, “Weird. Cool. Whatever.” There aren’t these strict lines anymore, whereas back then it was very strict, particularly, I think, in Chicago [where Minty Fresh was headquartered]. We would be asked in the press about whether Minty Fresh was a fake indie. People cared so much about that, because Veruca Salt had signed with Geffen [DGC Records, a label founded by media mogul David Geffen] after starting on Minty Fresh and there was a backlash against them. In retrospect it’s all so silly.

Keith: One of my proudest things about the band is opening for the Flaming Lips. That was a crazy thing, because that was a band I loved, and all of a sudden they’re asking us to tour with them.

Shivika: Out of all of us, I think I was the one, the whole time, who was the most uncomfortable touring. Now I can look back and be like, “Touring was awesome,” but during it I was pretty difficult. I was not an easy companion on tour. I was whiny, I was uncomfortable — there were no comfort zones. And there were very few women on the road when we would travel, so that was tough for me. Sometimes we’d try to remedy that — like, Donna Coppola came on tour with us, my friend Leah Stewart came on tour with us. But that’s definitely something I noticed all seven years of touring and being in the band — there are just so few women around. [Coppola, a classmate from Tufts, acted as a roadie for Papas Fritas in 1997, and Chris Colthart, a childhood friend and postcollege roommate of Keith Gendel’s, performed the same role in ’95. Both joined the group’s lineup for the Buildings and Grounds tour — Coppola on keyboards, Colthart on guitar — while their own band, the Solar Saturday, was rechristened the Faraway Places after a move from Boston to Los Angeles in the early aughts. Gendel and Tony Goddess helped engineer their first album, 2003’s Unfocus on It, and mix their second, 2009’s Out of the Rain, the Thunder & the Lightning. —Ed.]

Papas Fritas’s roadies from 1995 to ’97 included, from left, Dave Gartner, Chris Colthart, Donna Coppola, Ed Buck, and Matt O’Keefe. (photo credit: Keith Gendel)

Keith: We ended up splurging on a meal in Big Sur [in the fall of ’95]. I think I spent around $25. I wrote in my tour journal that it was the first time that I ever treated myself to a nice meal.

Tony: The philosophy of Papas Fritas was “We play the cheapest shit because that’s all we can afford, and it’s held together with duct tape, but it sounds like us.”

Shivika: I did love traveling across the country — that part was really fun. But in general, tour after tour, you’re like, “Fine, whatever.” One tour, we were with Blur. I was a huge Blur fan, and they ended up being nice and really friendly to us, and every day after the show they would ask us to hang out and party, and every day I’d be like, “No, no, I’m going to bed, sorry.” (laughs) I look back at that now and I go, “What was I thinking? Why did I do that?” But I did. I was like, “I have no interest in this at all. I don’t want to party. I want to go to sleep.” But if I were to tour now, I’d be a totally different person. Like, when we toured four years ago it was superfun — I was getting away from my life. Not that I want to get away from my life, but you know what I mean? Now it’s a break. Back then it was everything. That’s all we did.

Tony: When we toured with the Cardigans or Blur, we had a manager, Peter Leak, and he gave me some good advice. He was a British guy with a scratchy voice. He’d go, “Tony, you must get a tuner,” because I didn’t have a tuning pedal and I’d be tuning up through the PA. But he also drilled into us creating an opening set list so that you were playing your most convincing numbers at the end of the set as the headlining band’s fans are coming in.

Shivika: Europe was actually easier because we had a tour manager and someone taking care of stuff — we didn’t have to do as much work. And then you get to see Europe, and that was really awesome. So, there are good parts and bad parts.

Keith: [The 2011 reunion minitour of Europe] was so much more like a vacation than work. The early tours were amazing, positive experiences for me, but by the last tours, in 2000, it was really pretty hard to bear; I was tired of the routine and being at the mercy of relentless schedules designed to pack in as many shows as possible. But that one in 2011 was really fun, mostly because we organized it ourselves and brought our [spouses] with us. We set it up so we had a day off in every different town we went to in Europe to explore and sightsee and relax. It wasn’t grueling at all, like past tours. [Sam Goddess, Tony’s wife, joined Papas Fritas on keyboards for their 2011 reunion shows. Tony and Sam have performed together since 2009 as the Goddesses. —Ed.]

Shivika: For me, it was awesome because our families were there, or at least my family was there. My daughter came — she was five at the time — and she still remembers it, so that’s worth it for me. If she can remember seeing me onstage in Paris and thinks it was cool, then I’m happy.

“I won’t drag you down / I know, it’s only rock and roll”

— “Explain,” Papas Fritas, 1995

Tony: When the band started, it was a bit of Three Musketeers trying to get everyone feeling equally involved and equally invested. For the second record, it was maybe even more so. And we knew the band was over, more or less, making the third record, though when the record was done, Shiv was like, “I think we should go on tour.” It was always hanging on Shiv’s approval.

Shivika: I feel like it was just natural that we would go on tour. But I guess I was the one who had a job where I had to ask for time off. Maybe I just had more going on in my life then, so I had to fit touring into my schedule.

Keith: I’d been telling myself for many years that I had to get out of Boston. I finally left after our last Buildings and Grounds tour, in 2000, so we couldn’t really play together anymore. I realized, “I can go someplace with beautiful weather that’s cheaper.” L.A. at the time was also a much better place to be if you didn’t want to have a regular 9-to-5 existence. I thought I’d get involved in music production or sound production or something.

Shivika: We broke up because I wanted to go to grad school [for public health]. But we all thought it was time. So, “If this is the time to break up, let’s tour and then we’ll do our own thing, we’ll go our separate ways.”

Tony: You do calcify a little. By the end I don’t think our hearts were that into it. I still loved it, but that desire to be creative every night when you’re exhausted— You just figure out a set that really seems to open good and have a nice flow and then really ends with a bang, so you have a tendency to want to stick with what works.

Keith: On my way to L.A. I stayed in Houston for a few weeks. I met my wife and ended up postponing my trip to California for a few months, then we moved together. Before moving I was working with my father [an architect in Houston] and confirmed that all along I really wanted to be an architect, so I went to graduate school in California a couple of years later for architecture. All of my songs were about buildings, so it was underneath the surface the whole time anyway.

Shivika: When I was in the band I did web stuff to support myself, and it was nice because I could freelance. Now I’m a front-end web developer; I’ve been doing it for probably eight to ten years full-time. I did public health for a while, but I’ve always done web work on the side.

Tony: I basically spent ten years in Papas Fritas, and when that ended I was like, “I just want to be a bass player in a band, I want to record bands, I want to write songs with people. The last thing I want to do is put all of my energy into one thing.” But I was insecure: “Well, I know how to make music with these people, but I don’t know if I know how to make music with anyone else.”

I wrote a song with the band Guster [“Amsterdam,” from Keep It Together, 2003] that was their single on Warner Bros. I wrote songs with this dude named Bleu that wound up on this ELO tribute record he did [Alpacas Orgling, 2006]. I also played in this freak-out band called Sunburned Hand of the Man, so I was like, “I wrote a song with the most melodic band out there, Guster, and I opened for Sonic Youth with the most freaky band I’ve ever been in” — this is what I wanted, you know.

But now it’s ten years again. It wasn’t my plan to spend ten years being in local bands and stuff, but when that TV commercial [for Dentyne Ice] happened in 2003 it was considered a good tax move to buy recording equipment and vintage gear.

Tony: My accountant told me to spend $30,000 on equipment. I was like, “Thirty thousand dollars? That’s more than I made in the last three years.” “Well, you can spend $30,000 on equipment or you’re going to have to pay $25,000 in taxes. Take your pick.” It wasn’t quite those numbers, but that equipment counted as tax-deductible business expenses. That was mind-blowing — like, “Wow, I made more money from those 30 seconds of TV than I did from eight years of touring?” And also, not to sound so money obsessed, but I had just turned 30 years old and now money mattered a little bit more — I needed health insurance, I needed to go to the dentist. When I was 21 I could give a shit — I just wanted to party and play guitar.

I guess what I’m trying to say is, my life is filled with music. I’ve become a guy who’s recording other people more, because I wound up getting the equipment and you need guinea pigs to kind of test it out. I know there’s a sense of “Why isn’t he putting out his own records?” I want to do that. I have regrets that I haven’t, but I haven’t been sitting on my ass, either.

“Dried-up eyes will all be wet / We’re not finished yet”

— “Kids Don’t Mind,” Papas Fritas, 1995

Guests at the wedding of Tony and Sam Goddess (front row, sixth and seventh from right) on August 11, 2007, in Gloucester, Massachusetts, included Shivika Asthana (front row, fourth from right), Keith Gendel (front row, far left), Chris Colthart (front row, fourth from left), Donna Coppola (middle row, third from left), and Mat “Geech” Kessler (middle row, fifth from left).

Keith: Tony, from the day I met him, it was obvious he was born to be a musician. He was really serious about that. Music, for me, was always a hobby — you know, something that was just a joy. It never crossed my mind that I’d be in a band that would be on a record label and release records and tour around the world. That was not in my realm of possibilities, not until we were signed. It was always a shock.

Shivika: I never thought it would be something I’d be doing full-time. I’m certainly glad it ended up the way it did, but I definitely wasn’t expecting it. We had no expectations.

Tony: Bands are these funny things. I didn’t realize how lucky we were at that time, especially being kind of unique in terms of having this small woman on drums since so many bands are just (adopts macho tone of voice) four dudes playing guitar. You don’t realize, like, how do you get that freshness, and we weren’t even trying. And with the success thing, I didn’t realize how much success we were having when it was happening, I guess because I was an anxious twentysomething. I just wanted to make sure the lawyer was happy and the record company was happy. I didn’t realize I was living the dream.

Shivika: All of our goals were these little incremental things: “Oh, wouldn’t it be fun to play this show?” “Oh, wouldn’t it be fun to put out a 45?” “Oh, now we have a 45.” And then Minty Fresh contacted us. Everything happened really naturally and organically, and I think that’s why we kept doing it — because we weren’t stressed about that part of it. The stressful part is “Oh, shoot, is this level of the strings too loud?” All that nitty-gritty, creative stuff. But we didn’t go into college going, “We want to be in a rock band, and we want to tour, and we want to be famous.” That was not our intention at all.

Keith: Since the band split up in 2000, every time someone has called us up and said, “Hey, you want to reunite and play a show and we’ll fly you out to do it?” we’ve said yes. But it’s only happened three times — in 2002 for a neighborhood festival in Chicago, in 2011 for the Primavera Sound festival in Barcelona, and to tape an appearance on Yo Gabba Gabba! We’re game — we’re totally game! — if anyone ever asks us to play and they can help us get to where we need to be. I know we’d all love to play together again, but we’re all living in different cities and have kids and jobs and everything.

Shivika: I told Tony, “You know, it’d be so awesome to release a song for the 20th anniversary.” Because I’m a little ahead of Tony and Keith in terms of the kid thing — my youngest is five — I feel like I can see the light now, so I’m all gung-ho, like, “Let’s go, let’s do it!” And they’re like, “Easy — we’ve got little babies.” It’s a little harder.

Tony: Did you know about “Possibilities” getting turned into “Pretzelbilities”? It’s Snyder’s of Hanover’s new ad campaign.

The next town over is Rockport, and today three different ensembles of sixth, seventh, and eighth graders who had written songs and were going to be performing them later in the week came in to record them. The recording studio really provides a service for the community — it’s not just punk-rock bands or whatever. Sometimes it’s 70-year-old poets who want to do spoken word, or, like I said, it’s seventh graders with oboe, violin, and glockenspiel. It’s really enjoyable. But having a new TV commercial drop out of the sky on a song I remember us making up in the practice space 20 years ago is pretty awesome too.

Keith: I figured we’d be forgotten by now. Either that or totally famous because of the ’90s’ resurgence. (laughs)

Tony: I can’t believe how much energy I had. I mean, I guess I can because I was 19 years old and 20 years old, but I was so focused and enterprising. We would spend our vacations — you know, what now seems like work to me — going out on tour and sleeping on people’s floors. Of course now I say, “It was a great way to spend my 20s.”

Papas Fritas’s music can be purchased at both Amazon and iTunes. For an overview of the band’s discography, check out the Popdose Guide to Papas Fritas.

POSTSCRIPT, JUNE 2016: After this oral history was posted last December, Tony Goddess felt he was remiss in not mentioning Paul Q. Kolderie and Sean Slade, who mixed Papas Fritas. Here’s what he had to say about them via e-mail:

“I basically moved to Massachusetts because of Paul Kolderie and Sean Slade. For a few years it seemed like every record I loved was recorded and/or mixed by them at their home-base studio, Fort Apache: Dinosaur Jr.’s Bug, Sebadoh’s III, Das Damen’s High Anxiety, H.P. Zinker’s The Sunshine E.P., etc., etc. I used to walk the streets of Somerville fantasizing about running into J Mascis or Lou Barlow, not even realizing it was possible because Fort Apache was actually located in Somerville. So, a few years later when we got our record deal and the guys at Minty Fresh told me they knew Paul and Sean and suggested they mix our first single, I jumped at the chance.

“Turned out Paul lived blocks away from Hi-Tech City (a.k.a. 87 Electric Ave., a.k.a. the house Keith and I lived in). He came over with lunch, a guitar reverb, and what I now know as a multiband compressor and turned ‘Passion Play’ and the first version of ‘Lame to Be’ into actual records. I was blown away. When it came time to mix the full-length we didn’t even have to bring our eight-track deck (an Otari MX-5050, for the gearheads) into Fort Apache because the studio was started with the same machine and they still had it.

“Needless to say, the experience was awesome. Having done this for a few decades now, I know how difficult and occasionally tedious mixing can be, but we had none of that: with Paul and Sean at the desk it felt effortless. Hearing our music over great speakers in a great room was an instant and dramatic revelation. At the time we were all about keeping things sounding ‘dry,’ and Paul and Sean respected that while adding just enough reverb and delay to make the mixes more three-dimensional — and of course their compression and EQ techniques brought a ton to the party. They were willing to indulge our panning schemes and volume rides, plus my endless fanboy questions about records they’d made. They even asked us a few questions about how we’d achieved certain sounds, which made me feel tops. I think at that point they’d just come off of finishing Hole’s Live Through This, so it was quite validating to be worthy of working with two pros who were at the top of their profession, because Lord knows they weren’t mixing our record for the money. It took two days, six songs a day (since ‘Passion Play’ was already mixed), and we were done.

“Of course we continued to work with Paul and Sean as much as we could. They mixed Helioself at the Fort on their eight-track, and we tracked the basics on a few of the songs from Buildings and Grounds at a house Paul had decked out with a recording/rehearsal room. Eventually the Fort closed, but Paul reopened it for a few years under the name Camp Street, and I was always happy to track and/or mix records there with him and Sean and, later, their assistant engineer, Adam Taylor.

“Paul and Sean were, and are, huge influences on me. Paul turned me on to the Dwight Twilley Band, and Sean turned me on to Patto. That alone would make them friends for life, but if they hadn’t given us so much positive encouragement and support and done such a great job mixing our first two albums, I don’t think we’d even be talking about Papas Fritas 20 years later. Thanks, guys!”

In an e-mail of his own Keith Gendel added, “Watching them mix our songs was really a trip. These were the days before automation — every adjustment had to be done on the fly and almost choreographed like a dance. They blasted the songs through these huge speakers and physically exaggerated every little knob twist or switch toggle. I learned that a good mix is really a performance, just like with the musicians playing their instruments. Paul and Sean also introduced us to sushi, which somehow I had never really eaten before.”

Finally, Tony revealed that after Papas Fritas opened for former Replacements guitarist Slim Dunlap in St. Louis in March 1994, Dunlap wrote “Little Shiva’s Song,” a track inspired by Shivika Asthana that appears on his second album, Times Like This (1996). “He bought our 45 and cassettes and came to see us the next time we played Minneapolis,” Tony wrote, but “he told me he was bummed ’cause Shiv wasn’t singing on them!”

Comments