What America wanted most was a charismatic leader, someone who said outrageous things to and at the system who, through the cult of personality, mobilized those who were seldom heard and often disregarded. He came in and altered the landscape merely with his presence. Occasionally he spoke with clarity and defiance, but most often, he spoke in riddles, crashing words into each other because they sounded better that way, not because the verbal juxtaposition revealed meaning. The crowds derived their own meanings, and because they were the unwitting architects of definitions, the conclusions sounded right to them. They filled in their own blanks, did the heavy lifting for him, and summarily called him a genius.

I’m not talking about who you think I’m talking about.

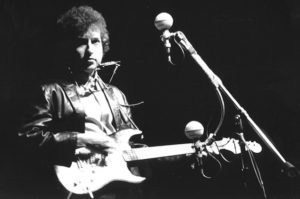

Bob Dylan is a costume, not only worn by Minnesota native Robert Allen Zimmerman, but by hundreds — maybe thousands — of musicians who saw him as a counter-cultural firebrand, come to lead the new protest movements of the 1960s to some other promised land. Does calling the persona of Dylan a costume sound harsh, or worse, heretical? Maybe you’re still in his thrall.

Bob Dylan is a costume, not only worn by Minnesota native Robert Allen Zimmerman, but by hundreds — maybe thousands — of musicians who saw him as a counter-cultural firebrand, come to lead the new protest movements of the 1960s to some other promised land. Does calling the persona of Dylan a costume sound harsh, or worse, heretical? Maybe you’re still in his thrall.

The ’60s were, by all accounts, turbulent times. Identity was a concept people began playing with, and what constituted one’s role in society was shifting as well. There were bound to be protests, but these soon became more than the act of voicing one’s displeasure or outrage with the world around them. For some, this became the thing to do, not just the means to an end but the purpose-built end for itself. Protests were social events, and even though many had legitimate intentions, several used the scene to be seen.

By his occasional accounts, the former Zimmerman wanted to be seen. He wanted to be famous. And in the earliest days of his career, he put on several outfits to figure out who he was to be. We are exposed to some of them even today, canonized as they are in the fabric of pop culture. Roger McGuinn and The Byrds should be as grateful to Tommy Makem and The Clancy Brothers as they are to Bob Dylan for giving them as big a hit as “Mr. Tambourine Man” was.

But the acolytes he picked up along the way used his words maybe, shall we say, a bit too reverentially.

But the acolytes he picked up along the way used his words maybe, shall we say, a bit too reverentially.

Think about this: aside from The Byrds, The Turtles, Joan Baez and scores of other figures from the 1960s, many, many people were singing Dylan songs. A cursory scan of the music of the times would reveal him to be one of the most covered artists of the era, if not of all time. It seemed plenty of people wanted to wear the Dylan costume too.

And why not? The quality of protest chants has barely improved over the course of 50-plus years. They still trot out “Hey hey, ho ho, Insert Noun has got to go,” with the satisfaction that it is at least a little more clever than another “Got Milk?” parody. Therefore, Dylan’s first run at folk music, informed with the spirit and genuine reverence for his hero Woody Guthrie, carried real weight and sincerity. “The Times They Are A’Changin'” was likely created with a modicum of sincerity. Those who adopted it were likewise sincere, much to their own detriment. The folk trio Peter, Paul, and Mary lifted the song to the same lofty heights as spirituals and “We Shall Overcome.”

That might have been, in hindsight, a mistake. As the trio’s own Peter Yarrow once noted during a documentary about Dylan, “Everyone wanted to be near Bobby, to be with Bobby…to get high with Bobby. To sleep with Bobby.” As a means of inflation of one’s ego, you couldn’t do better than crowning an individual the sole voice of a generation. The adornments both suited and chafed the musician. Known for his penchant for tweaking the establishment, once he had himself become the establishment for the protest-minded, Dylan had to tweak himself. His lyrics became more abstract, but his adherents insisted there were layers of meaning and righteousness in them. He went electric, and a few more were up in arms over that. His electric appearance at the Newport Folk Festival found him clashing with another folk luminary (although one from a different generation), Pete Seeger.

That might have been, in hindsight, a mistake. As the trio’s own Peter Yarrow once noted during a documentary about Dylan, “Everyone wanted to be near Bobby, to be with Bobby…to get high with Bobby. To sleep with Bobby.” As a means of inflation of one’s ego, you couldn’t do better than crowning an individual the sole voice of a generation. The adornments both suited and chafed the musician. Known for his penchant for tweaking the establishment, once he had himself become the establishment for the protest-minded, Dylan had to tweak himself. His lyrics became more abstract, but his adherents insisted there were layers of meaning and righteousness in them. He went electric, and a few more were up in arms over that. His electric appearance at the Newport Folk Festival found him clashing with another folk luminary (although one from a different generation), Pete Seeger.

In a famed and sometimes disputed tale, Seeger was either so incensed, angered, or both that he hoisted an actual chopping axe and threatened to cut the power, or an amplifier…you can see how this legend has become more than muddy. The folk fans felt betrayed, and in some circles it is said that Dylan was treated as a pariah. That’s might be the case, but few pariahs enjoy such a level of parallel adoration.

I don’t want the reader to come away thinking that Dylan is not deserving of most of his accolades for music. Someone who has survived and sustained such a career must be doing more than collecting groupies and hangers-on. But I want to get at the psychology of those groupies and hangers-on, the people who saw Dylan as something of a prophet or mystic, and were so willing to suspend their own voices and opinions to adopt his. In an era that was so much about individual expression, such as we’ve all been told, why was it that so many chose to let him be their leader? Why did so many want to wear his costume? And for a generation that spoke so fervently about changing the world, when given the individual mandate to contribute, why did they so easily abdicate that power?

I don’t want the reader to come away thinking that Dylan is not deserving of most of his accolades for music. Someone who has survived and sustained such a career must be doing more than collecting groupies and hangers-on. But I want to get at the psychology of those groupies and hangers-on, the people who saw Dylan as something of a prophet or mystic, and were so willing to suspend their own voices and opinions to adopt his. In an era that was so much about individual expression, such as we’ve all been told, why was it that so many chose to let him be their leader? Why did so many want to wear his costume? And for a generation that spoke so fervently about changing the world, when given the individual mandate to contribute, why did they so easily abdicate that power?

Musicians were still keen to ride the wake of Dylan’s rolling thunder, long after Newport, long after the U.K. tour with what became The Band, after the motorcycle crash, after “Lay, Lady, Lay.” Even fans who claimed publicly that they now reviled their idol never fully broke away from him. He remained a charismatic leader, someone who said outrageous things to and at the system who, through the cult of personality, mobilized those who  were seldom heard and often disregarded. He came in and altered the landscape merely with his presence. And maybe, because they were so malleable, this led others to believe and act upon a fatal flaw in the human mindset: Power is its own ecosystem. It fuels itself. It sustains itself. It attracts like nothing else. It grows and it controls.

were seldom heard and often disregarded. He came in and altered the landscape merely with his presence. And maybe, because they were so malleable, this led others to believe and act upon a fatal flaw in the human mindset: Power is its own ecosystem. It fuels itself. It sustains itself. It attracts like nothing else. It grows and it controls.

In the end, did Dylan’s fans love his ideas, his music, his wordplay, his rebel status, or did Dylan’s fans love him because he had a hell of a lot of fans?

Comments