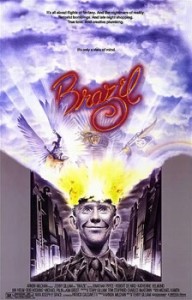

25 years ago, on December 18, Terry Gilliam’s Brazil was released in the U.S. — thus ending one of the most famous battles in Hollywood history of a director taking on a movie studio and winning.

Brazil is set “somewhere in the 20th century” in some kind of Orwellian world where not only is Big Brother watching, but requires the proper paperwork to do so. The government is so inept, it’s comical — yet at the same time the system is quite capable of doing really terrible things.

Brazil is set “somewhere in the 20th century” in some kind of Orwellian world where not only is Big Brother watching, but requires the proper paperwork to do so. The government is so inept, it’s comical — yet at the same time the system is quite capable of doing really terrible things.

Our “hero” of the story is Sam Lowry, a meek government employee played beautifully by the great Jonathan Pryce. I remember being amazed at the time by how Pryce could go from playing the menacing Mr. Dark in Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983) to playing such a hapless soul in Brazil.

Sam Lowry works for the Ministry of Information and wakes up each morning to a fully-automated breakfast-making machine that, like most everything in this society, never quite works properly. The machine pours coffee all over his toast which leads to a funny bit of physical comedy where he attempts to eat the soggy piece of toast but it keeps flopping about in his hand. His ineffectual boss (Ian Holm), afraid of getting his own hands dirty, is delighted when Sam volunteers to hand-deliver a refund check to Mrs. Buttle, a woman whose husband was falsely arrested and tortured to death by the government — it seems the Buttles were overcharged for “information retrieval procedures.”

Sam Lowry works for the Ministry of Information and wakes up each morning to a fully-automated breakfast-making machine that, like most everything in this society, never quite works properly. The machine pours coffee all over his toast which leads to a funny bit of physical comedy where he attempts to eat the soggy piece of toast but it keeps flopping about in his hand. His ineffectual boss (Ian Holm), afraid of getting his own hands dirty, is delighted when Sam volunteers to hand-deliver a refund check to Mrs. Buttle, a woman whose husband was falsely arrested and tortured to death by the government — it seems the Buttles were overcharged for “information retrieval procedures.”

The shifting tone of the film — ranging from the silliness of someone attempting to eat a soggy piece of toast to a devastating moment where a grieving widow wonders what the government has done with the body of her husband — is probably what I love about it the most.

The shifting tone of the film — ranging from the silliness of someone attempting to eat a soggy piece of toast to a devastating moment where a grieving widow wonders what the government has done with the body of her husband — is probably what I love about it the most.

Brazil opened in Europe in February 1985 where it was distributed by 20th Century Fox. The U.S. rights would be controlled by Universal, a similar deal worked out for Ridley Scott’s Legend by producer Arnon Milchan who produced both films. Interestingly both films would be subjected to studio interference when it came to each of their respective U.S. releases. In the case of Brazil, President of Universal Sid Sheinberg wanted to completely re-edit sections of the film to make Sam Lowry more of a sympathetic character and also alter the ending in such a way that it would be more uplifting. However, Sheinberg’s ending makes no sense in terms of other nightmarish events depicted in the final reel (such as how the Tuttle character vanishes amidst a pile of paperwork).

One example of a change relating to Sam’s character occurs in the aforementioned scene in which Sam brings the check to Mrs. Buttle. Sheinberg felt that Sam showed too little sympathy in the scene so he wanted to omit any references showing that Sam had any knowledge of Mr. Buttle’s death. This is beyond stupid for a multitude of reasons but most importantly it ignores the fact that this kind of behavior is prevalent in this world, that all of these horrible things are happening and people are indifferent to it all, which is one of the more disturbing aspects of this society. In fact, one could make an argument that Sam is actually doing a good deed in this world by discovering a mistake and doing what he can within the system to rectify it.

Gilliam co-wrote the screenplay with Charles McKeown (who plays Harvey Lime, a man who shares half an office and half a desk with Sam — another great bit) and also playwright Tom Stoppard. Gilliam credits Stoppard for adding elements to the story that helped tie things together, such as the whole Tuttle/Buttle confusion. In original drafts “Buttle” was just someone falsely arrested, but Stoppard made his name similar to the actual wanted man of the story, Tuttle — which helps to better illustrate the utter ineptitude of the system that an arrest report can be so easily altered by one letter simply because a bug falls into a teletype machine.

Harry Tuttle is played by Robert De Niro, who is barely recognizable in his hood and silly oversized glasses with little flashlights mounted on each end. Tuttle is a rebel in this world, a renegade heating engineer who does his work without any regard for proper protocol or paperwork. He gets around by repelling great distances on ropes. I remember seeing this in the theater and the entire audience gasping when Tuttle first leaps off a building and effortlessly glides down what’s got to be 40 stories. His heroics are accompanied by composer Michael Kamen’s little 4-note heroic motif, as if to sing out his name ‘Har-ry Tut-tle.”

Harry Tuttle is played by Robert De Niro, who is barely recognizable in his hood and silly oversized glasses with little flashlights mounted on each end. Tuttle is a rebel in this world, a renegade heating engineer who does his work without any regard for proper protocol or paperwork. He gets around by repelling great distances on ropes. I remember seeing this in the theater and the entire audience gasping when Tuttle first leaps off a building and effortlessly glides down what’s got to be 40 stories. His heroics are accompanied by composer Michael Kamen’s little 4-note heroic motif, as if to sing out his name ‘Har-ry Tut-tle.”

The film is filled with striking imagery, a Gilliam trademark, much of which comes from Sam’s recurring dreams that depict, among other things, buildings rising from the very earth and a metallic samurai warrior who literally bleeds fire — that’s right, not breathes fire, bleeds it.

Gilliam had already made cuts of his own of the film for American audiences in an attempt to get the running time down, but still Universal wouldn’t budge. And so, Terry Gilliam, in breach of his contract, held a series of secret screenings in the LA area. On December 14 1985, in the back room of the Beverly Hills Gun Club, the Los Angeles Films Critics Association held a meeting and voted Brazil best film of the year, along with best director and best screenplay. Sid Sheinberg and Universal finally relented, and Gilliam’s American version of Brazil was released. For fans of films who had been following this story, it was a great victory.

Gilliam had already made cuts of his own of the film for American audiences in an attempt to get the running time down, but still Universal wouldn’t budge. And so, Terry Gilliam, in breach of his contract, held a series of secret screenings in the LA area. On December 14 1985, in the back room of the Beverly Hills Gun Club, the Los Angeles Films Critics Association held a meeting and voted Brazil best film of the year, along with best director and best screenplay. Sid Sheinberg and Universal finally relented, and Gilliam’s American version of Brazil was released. For fans of films who had been following this story, it was a great victory.

The whole ordeal is documented in the Jack Mathews book The Battle of Brazil (1987) and also as a supplement on the Criterion DVD where at one point (at the end of the following clip) you can hear an excited phone message left on Gilliam’s answering machine informing him of the good news about the Los Angeles Film Critics Association’s awards.

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/tPB8gKlcBts" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

Comments