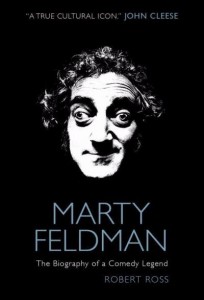

Marty Feldman: The Biography of a Comedy Legend, by Robert Ross

Marty Feldman: The Biography of a Comedy Legend, by Robert Ross

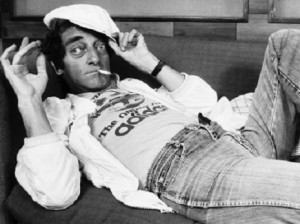

Between 1974 and 1976, Marty Feldman was the funniest person on the planet, to me, and to anyone who saw him in Mel Brooks’ Young Frankenstein and Silent Movie (and, in between those classic comedies, Gene Wilder’s The Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Younger Brother, which gets a lot of its chuckles from his contributions). Feldman’s face was his fortune, but a gift for physical comedy, a way with improvisation, and crack timing accompanied those beloved bulging eyes. Watching the Brooks films again on Blu-ray recently, Feldman made me laugh as hard as he did when I was 11 years old. “What…hump?” He kills.

Almost 30 years after his untimely death in 1982 Feldman is in danger of becoming a footnote, particularly on this side of the Atlantic, where his reputation rests on those movies (plus his own The Last Remake of Beau Geste, one of the few films to hold its own against the Star Wars juggernaut in the summer of 1977). Robert Ross pulls him back from the brink with this biography, which can’t help but be a lively read, given the company he kept, and his own effusive personality.

For American readers, this book pretty much begins with Chapter Thirteen, when Feldman leaves a burgeoning TV career in his native England for Hollywood. But Ross, who has written books on Monty Python and the Carry On movies, expertly traces the deep artistic roots of his too-brief life. “Like a clown in kit form,” is how a friend recalls him, yet some assembly was required for the East End-born Jew, a jazz enthusiast and dropout, to embrace his destiny. His admiration of Buster Keaton and vaudeville performers of yore spilled into some dodgy stage acts that he toured England in, and the knocking-about years are fun to read about. That all this was fueled by stress, overwork, and what became a six-pack-a-day cigarette habit, however, took its toll; Graves’ disease set in, and it was thyroid treatments that led to his unique appearance. Feldman, who was now writing comedy, rolled with it. “His popped eye would be the curse and blessing for the rest of his life,” Ross notes.

A blessing, in that it created a “mischievous dwarf” persona that brought him celebrity, and ready cash for his spendthrift ways. And a curse, in that Feldman felt he had more to offer creatively, as a writer, performer, and director, as he moved up the ranks in TV sketch comedy to his own, envelope-pushing, scattershot shows, where he worked with Spike Milligan, the Pythons (Michael Palin and Terry Jones reminisce), and Tom Lehrer while swinging through the 60s. Drug and alcohol problems followed him into the 70s, but Feldman, who maintained a basic innocence and equilibrium even when downing a bottle of vodka at breakfast, had his greatest success collaborating with Brooks and Gene Wilder. “If it’s overnight success it’s been a very long night,” he quipped.

The surprise popularity of his own Beau Geste (in typical, make-the-best-of-it Feldman fashion, he planned a “last remake” of The Four Feathers, but got the properties mixed up) landed him a five-picture deal with Universal, which promptly collapsed with his next and last movie, In God We Tru$t (1980). Ross makes a case for it as a stinging satire of U.S. fundamentalism, with Feldman airing his grievances about American hypocrisy. The trouble was, he forgot to bring the funny–as I can attest, having obliged my parents to take me to see it one bright sunny Saturday, and the three of us sitting grimly in the theater (there’s nothing worse than being primed to laugh, and not laughing). Having bit the hand that fed him, and, worse, having failed at it (a Life of Brian-type success might have opened new opportunities), Feldman’s career was on ice. A comeback was not to be: beset by health problems he died in Mexico City on the set of the posthumously released pirate spoof Yellowbeard (1983), age 48.

The surprise popularity of his own Beau Geste (in typical, make-the-best-of-it Feldman fashion, he planned a “last remake” of The Four Feathers, but got the properties mixed up) landed him a five-picture deal with Universal, which promptly collapsed with his next and last movie, In God We Tru$t (1980). Ross makes a case for it as a stinging satire of U.S. fundamentalism, with Feldman airing his grievances about American hypocrisy. The trouble was, he forgot to bring the funny–as I can attest, having obliged my parents to take me to see it one bright sunny Saturday, and the three of us sitting grimly in the theater (there’s nothing worse than being primed to laugh, and not laughing). Having bit the hand that fed him, and, worse, having failed at it (a Life of Brian-type success might have opened new opportunities), Feldman’s career was on ice. A comeback was not to be: beset by health problems he died in Mexico City on the set of the posthumously released pirate spoof Yellowbeard (1983), age 48.

Even in his last, depressing patch there were bright spots, notably his mentoring of an eternally appreciative David Weddle, who has gone on to write and produce episodes of Deep Space Nine, Battlestar Galactica, and CSI. Ross’ biography is neither hagiobiography nor hatchet job, and he’s rounded up the right people to comment on Feldman’s short, sometimes chaotic, perhaps unfulfilled–and, more than once, brilliant–life, notably Palin (my goal in life is to become famous, befriend Michael Palin, and, assuming I pre-decease him, have him say observant, affectionate things about me to my biographer) and close friends who were entertained and exasperated by his antics. His best source is the man himself–candid, introspective, and self-deprecating notes Feldman left for a planned autobiography provide a strong foundation. Ross as well deftly recreates the vanished worlds of British theater and TV that loosed Marty Feldman on an unsuspecting planet. In short, a fine tribute to a comedy king.

Which you can read while looking up choice bits of Feldmania on YouTube. Like this one:

[kml_flashembed movie=”http://www.youtube.com/v/GlPAVm8Gl6M” width=”600″ height=”344″ allowfullscreen=”true” fvars=”fs=1″ /]

Comments