My cousins Chuck and Dwight—who were like older brothers to me, and whose record collections I coveted—were Jersey guys, born and bred, back in the day when the term Jersey guy meant this guy or this guy, not this guy. At the same time, they were Southern boys at heart; their collections were shot trough with Southern rock staples—Allman Brothers, the Outlaws, Marshall Tucker Band, Charlie Daniels Band, .38 Special, Molly Hatchet (particularly that initial run of awesome titles produced by official Popdose innkeeper Tom Werman), and the almighty Lynyrd Skynyrd and its offshoots, Rossington Collins Band and little brother (and future frontman) Johnny Van Zant. This made total sense; the period we’re talking about here was roughly mid-Seventies through maybe 1982 or 1983, when the flagship bands of the genre were making their best records, when Daniels’ annual Volunteer Jam festival shows were broadcast around the world, and when the unfathomable Skynyrd tragedy shook Southern rock to its core, depriving the genre of its flagship act and, in Ronnie Van Zant, arguably its most eloquent songwriter and spokesman.

My cousins Chuck and Dwight—who were like older brothers to me, and whose record collections I coveted—were Jersey guys, born and bred, back in the day when the term Jersey guy meant this guy or this guy, not this guy. At the same time, they were Southern boys at heart; their collections were shot trough with Southern rock staples—Allman Brothers, the Outlaws, Marshall Tucker Band, Charlie Daniels Band, .38 Special, Molly Hatchet (particularly that initial run of awesome titles produced by official Popdose innkeeper Tom Werman), and the almighty Lynyrd Skynyrd and its offshoots, Rossington Collins Band and little brother (and future frontman) Johnny Van Zant. This made total sense; the period we’re talking about here was roughly mid-Seventies through maybe 1982 or 1983, when the flagship bands of the genre were making their best records, when Daniels’ annual Volunteer Jam festival shows were broadcast around the world, and when the unfathomable Skynyrd tragedy shook Southern rock to its core, depriving the genre of its flagship act and, in Ronnie Van Zant, arguably its most eloquent songwriter and spokesman.

What often gets lost in the conversation about Southern rock was how fucking good the bands were, how accomplished their players were as musicians. Say what you will about their accents and fashion and rebel flag iconography—the best of the bunch could flat out play. Outlaws stalwart Hughie Thomasson (who later played in the reconstructed Skynyrd) was a terrific songwriter and a monster picker. Charlie Daniels was (and still is) an untouchable fiddle player. The Allman Brothers’ original guitar attack of Duane Allman and Dickie Betts set the standard that many to this day try (and fail) to duplicate. And I will this moment buy a pair of shitkickers for the sole purpose of standing in them and declaring that Steve Gaines’ death in the Skynyrd plane crash was as significant to Southern rock as Randy Rhoads’ death was to hard rock and metal—both deaths silenced young virtuosos with fully formed instrumental voices and miles of potential (don’t believe me? Listen to Street Survivors again. Then kiss my shitkickers).

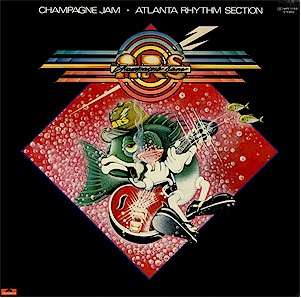

One band that fit nominally in the framework of Southern rock (cuz they were from Georgia and could, on occasion, you know, rock) was Atlanta Rhythm Section. They were kinda the Toto of the redneck set—studio musicians brought together as a house band for a Doraville, GA recording facility, backing folks like Roy Orbison and other lesser names during the day, recording their own stuff during off hours. Eventually some of that stuff got pressed on vinyl and attracted attention outside the Atlanta region. Chuck and Dwight had a few of their records, including A Rock ‘n’ Roll Alternative (1976), which spawned the hit “So Into You,” and 1980’s Quinella, which scored a Top 30 single in “Alien.”

One band that fit nominally in the framework of Southern rock (cuz they were from Georgia and could, on occasion, you know, rock) was Atlanta Rhythm Section. They were kinda the Toto of the redneck set—studio musicians brought together as a house band for a Doraville, GA recording facility, backing folks like Roy Orbison and other lesser names during the day, recording their own stuff during off hours. Eventually some of that stuff got pressed on vinyl and attracted attention outside the Atlanta region. Chuck and Dwight had a few of their records, including A Rock ‘n’ Roll Alternative (1976), which spawned the hit “So Into You,” and 1980’s Quinella, which scored a Top 30 single in “Alien.”

These records (and, I’m assuming, several—if not all—others in the ARS discography) were notable for their schizophrenic sensibilities. As studio musicians, the band played things in a clean, exact manner—great for the ballads on the records (which sounded like much of the softer AM radio fodder of the time), but when the crew attempted to rev things up, Skynyrd style, it all came off as, well, too clean and exact. Sometimes, it all worked—Side One of Quinella is terrific uptempo twang, while Side Two brought the proverbial room down a bit. A Rock ‘n’ Roll Alternative alternates between heavily polished rock and even more heavily polished down-tempo material.

The ARS record I gravitate toward is Champagne Jam, which followed A Rock ‘n’ Roll Alternative by a year and which amplifies the strengths and challenges of the band’s approach. I imagine it sounded pretty good blasting out of Chuck’s speakers, though the FM radio sheen can be a little distracting—when you’re playing Southern rock, it’s good to get a little raw sometimes.

Side One’s first track typifies the should-be-raw-but-ain’t issue. “Large Time” boasts of the party-startin’ prowess of the band, how they’re “Proud to be livin’ in the USA / Playin’ for the ARS.” Yes, they name-check themselves in their own song, but they also name-check Lynyrd Skynyrd and “Free Bird,” so it’s sort of okay. But for a track about rockin’ the house and flyin’ the flag, the sound is awfully tame, like Steely Dan playing “Sweet Home Alabama.” Guitar guru Barry Bailey gets in some solid lickage, but there’s little in the way of bite, and bite is absolutely necessary.

The laid-back strategy works perfectly on the midtempo shuffle of “I’m Not Gonna Let It Bother Me Tonight.” Welcome back my friends to the worn-out malaise of America in the Carter administration:

The world is one big tragedy

I wonder what I can do

About all the pain and injustice

About all of the sorrow

We’re living in a danger zone

The world could end tomorrow

But I’m not gonna let it bother me tonight

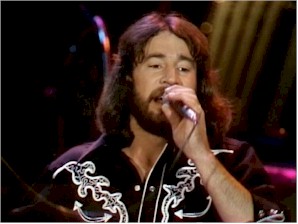

Ronnie Hammond’s voice is the perfect lead instrument here, dour without being whiny, soulful without resorting to clichÁ©. It’s a pop song, and it works well as a pop song; the radio-ready production is fitting here, as it is on the big, big piano ballad “Normal Love.” There’s vulnerability in Hammond’s delivery as he opines for good, old-fashioned missionary-position-and-a-nap-afterwards-kinda lovin’—leave the freakin’ and the kinky stuff to the groupies; he needs to snuggle. “Make it sweet, make it simple,” he sings. “Ooh, that’s what I need / Just a smile, just a kiss / Normalness—what a twist.” The 10cc-ish background harmonies feed the overall lulling atmosphere—it’s really well done.

Ronnie Hammond’s voice is the perfect lead instrument here, dour without being whiny, soulful without resorting to clichÁ©. It’s a pop song, and it works well as a pop song; the radio-ready production is fitting here, as it is on the big, big piano ballad “Normal Love.” There’s vulnerability in Hammond’s delivery as he opines for good, old-fashioned missionary-position-and-a-nap-afterwards-kinda lovin’—leave the freakin’ and the kinky stuff to the groupies; he needs to snuggle. “Make it sweet, make it simple,” he sings. “Ooh, that’s what I need / Just a smile, just a kiss / Normalness—what a twist.” The 10cc-ish background harmonies feed the overall lulling atmosphere—it’s really well done.

Of course, on Side Two, you get plenty of non-“normal”-type loviny-doviny on “The Ballad of Lois Malone”—a tribute to a woman of loose morals who sounds like a whole lotta fun—and the album-closing “Evileen,” a sweet thang who’s both “a wicked woman” and “a necessary evil, because she’s got what I need.” Tell us more, you say, she sounds lovely. Hammond is happy to oblige:

Sometimes her love’s a nightmare

Sometimes it’s obscene

She makes me fuss

She makes me cuss

But I love that very, very

Kinky and contrary Evileen

Now this is the kinda lovin’ one expects a dude in a road-travelin’ Seventies Southern rock band to be getting on a fairly regular basis. One can imagine the details he’s leaving out (“She makes me wear the diaper,” “She makes me lick her boot heels,” “She makes me put on lipstick,” etc.), but that’s okay; we get the picture.

And speaking of pictures, there’s “Imaginary Lover,” ARS’ masterstroke (so to speak)—a four-minute slow-burning ode to self-satisfaction that’s still played on Adult Contemporary radio to this day. This is what happens when you’re in a road-travelin’ Seventies Southern rock band and you don’t get “Normal Love,” nor abnormal love (nor Abby Normal love)—you and Rosie do the Vaseline tango in the back of the tour bus:

Imaginary lovers

Never turn you down

When all the others turn you away

They’re around

It’s my private pleasure

Midnight fantasy

Someone to share my

Wildest dreams with me

Imaginary lover

You’re mine anytime

It’s a great song—perfect soft-rock radio fodder for lazy late-Seventies lotharios everywhere. It didn’t have to be tough; toughness is not required when daydreaming about starlets and test-firing the baby cannon.

It’s a great song—perfect soft-rock radio fodder for lazy late-Seventies lotharios everywhere. It didn’t have to be tough; toughness is not required when daydreaming about starlets and test-firing the baby cannon.

Toughness is, however, required when one is singing about staying out late and jammin’ all night long, as ARS does, unconvincingly, on Champagne Jam‘s title track. Again, the slick production is too smooth, the playing too vanilla, to maintain the illusion of hard-livin’, hard-playin’ road dogs the band tries to conjure.

And, I gotta ask: why champagne? This is Southern rock, fercryinoutloud. I imagine the guys in Molly Hatchet coming by, Jack Daniels in hand, only to be turned away at the door—it was, after all, a champagne jam, not a sour mash whiskey jam. (Molly Hatchet would’ve then found someone who looked like bassist Paul Goddard and beaten the ever-loving shit out of him). Regardless, they’re talking about alcohol while sounding like milk—an approach that works on the slower songs, but not the uptempo material. Therein lies the conundrum of Atlanta Rhythm Section—a Southern rock band with bad intentions that was nevertheless easy on the ears, as well as the liver.

Comments