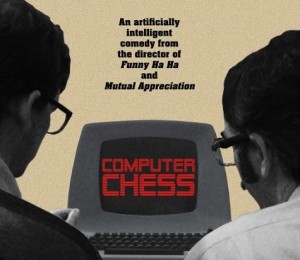

Lousy with comically ambiguous situations, Computer Chess watches a convention of software geniuses compete to prove their programs are capable of besting a human at chess. Writer/director Andrew Bujalski loves characters brazen enough to shoot the moon and dumb enough to use a slingshot. His band of crusaders, the Atari 2600s of their burgeoning industry, aren’t concerned they’re working towards human irrelevance. This is only one of a hundred reasons Computer Chess is called ”an existential comedy,” and Bujalski’s nods to the likes of Lynch, Cronenberg and Zulawski feel like confirmations.

The fact the whole goofy situation is predicated on a bet sounds crazy, but movies have a legacy of such gambling. Leland Stanford paid Edward Muybridge to photograph a horse and help him win a high priced bet all the horses’ legs came off the ground mid-stride. The result of the experiment would be part of the development of motion pictures; the result of this chess experiment, much of which is based on real conventions held through the 70s and 80s, is funnier and a lot harder to call.

You have film critic Gerald Peary playing Leland Stanford to a crowd of Muybridges. He’s got a bet that by 1984—an auspicious year—these people can invent a computer to beat a human at chess. Is the fact Peary’s running the show any intended subtext?

Not necessarily subtext. My career begins with him. The first time my debut feature Funny Ha Ha screened was at Coolidge Corner Theater in Boston it was programmed by Gerry. He holds a special place in my heart. Gerry’s been waiting for several decades for someone to ask him to star in a movie. One of my crew had been a student of Gerry’s at Boston University and we both giggled at the notion of Gerry in in the part because there is at this master of ceremonies aspect to the role which we’ve seen Gerry do—he also studied acting as a young fella and I think he was very excited to turn that on for us. He brought all his fire power.

Of course the bet is relevant; we’re making a movie about computer chess and artificial intelligence and the specifics end up feeling more relevant to our lives than I ever conceived they could when we started. It was an oddball fantasy in the back of my head: the most cockamamie, least viable thing I could think of. I went forward in that spirit—to do something no one on earth was asking for—and it wasn’t until I got further into it that everything in the film seemed to thematically correspond to our daily digitized lives. We’re living in an age of transition from analog to digital and I seem to have made something zeitgeisty, or dare I say even relevant, but that’s by accident. I’ve never made anything relevant before.

”The Turk” was a computer that bested a man at at chess…that was later revealed to have a little man inside it. It’s a great metaphor—a Trojan horse—like a comedy about the mystery of existence.

I came to the concept of computer chess as a skeptic. I had a humanist question in mind: ”Why do we want a machine to wipe us off the board?” Doesn’t that take the fun out of the game? I sympathize with that POV but in the course of making this and learning about the history of the pursuit—as much as I think there are unintended consequences, the pursuit of the computer chess programmers was as human a pursuit as making a movie. I do think there’s a specific skill to building a great chess program but at the time they were debating what they called ”brute force.” They said the way the computer could be good at chess was to crunch more numbers, better, faster. But others said ”no, that’s not how humans do it,” they don’t look at the board and calculate every possible move. Yet brute force was winning and the computer isn’t doing anything particularly smart it’s just doing it very fast. This many years down the line computers are doing things out of range of human ability and no human player can play at the level of computers—they keep getting better and better having left humans behind long ago and in some weird way I can make that analogy about humans. I guess they make more and more money, they’re bigger and bigger, but also seem to have left the humans behind. I also feel the line about ”turbo charged mediocrity” [used to describe brute force] is also a handy description of studio movies circa 2013.

One of my favorite moments is the conversation between the senior programmer and his junior when they’re trying to fix their program. The junior characterizes a computer error as suicide. The senior schools him saying ”it doesn’t have will” just as you see the programmers from the computer’s POV. I realize it’s a convention, but do you think all we need is a POV shot to make an object into a character?

There’s something very cheeky and silly about that shot and it makes me laugh but I think what you’re saying is right. To put a camera in the point of view of this old monitor, on a strict logical level doesn’t make sense at all. There’s no suggestion of a camera or a visual sensor in that monitor but everyone who sees that shot gets it instantly—maybe because there’s a similar shot in 2001—but everyone also assigns personality and motive to the computer just because of this piece of visual language. They ask, ”What is this consciousness?” and it helps set up where we’re headed but of course there are no answers. I don’t tend to traffic in answers, just in piling questions on more questions.

As the junior says, ”Temporary hallucination can have a lifelong effect on someone’s consciousness.”

It was a shock to me when I brought my first movie out in the world and found out it was divisive. I didn’t expect it to provoke people to rage and I’ve certainly never approached anything as a provocateur. This may be a cop out but I feel like I want it all to be fun, even if my movies challenge people. They’re fun for me and I have to leave it to the viewer how much they want to go longing for depth or not. It would be nice to think it works on all levels—you’re never going to satisfy everyone but certainly it’d be nice to think the movie could work for someone who looks for light entertainment or minds blown. It’d be nice to do both.

Comments