”Raymond Shaw is the kindest, bravest, warmest, most wonderful human being I’ve ever known in my life.”

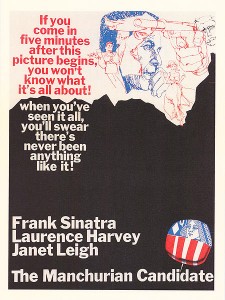

The Korean War. An Army unit is ambushed while on patrol in the countryside, their interpreter has double crossed  them. The soldiers get strapped down to gurneys and hoisted on to helicopters, flown away into the night skies with their fates uncertain. So begins The Manchurian Candidate, the 1962 film written by George Axelrod (adapted from the book by Richard Condon), directed by John Frankenheimer and starring Frank Sinatra, Lawrence Harvey, Janet Leigh, and Angela Lansbury.

them. The soldiers get strapped down to gurneys and hoisted on to helicopters, flown away into the night skies with their fates uncertain. So begins The Manchurian Candidate, the 1962 film written by George Axelrod (adapted from the book by Richard Condon), directed by John Frankenheimer and starring Frank Sinatra, Lawrence Harvey, Janet Leigh, and Angela Lansbury.

After that brief prologue, we soon learn what happened to those soldiers. Somehow, they escaped and were brought to safety by Sergeant Raymond Shaw (Harvey). Awarded the Medal of Honor, Shaw returns home a hero, with his politically minded mother (Lansbury) using his fame as a way to propel her second husband, a U.S. Senator, into the national spotlight. Raymond wants nothing to do with his mother or his step-father. He hates them both, HATES them. Raymond is given the opportunity of lifetime to work for a New York newspaper and tries to put the war and his family behind him.

Yet, there’s something very off with the story everyone’s being fed. What about those helicopters? Where did those soldiers get taken away to and just how is it possible that Raymond, a man who lacked the respect of his platoon and who seemed to barely know how to hold himself as a soldier, could actually become a hero? The intrigue builds. While Raymond’s life is going so grandly, we cut away to Major Bennett Marco, Shaw’s commanding officer. After returning from Korea, Marco is a wreck. He’s been having a recurring nightmare that involves his patrol watching Raymond kill two of his fellow soldiers while they sit by, idling their time away. When he’s placed on indefinite sick leave by the Army, Marco decides to find out what really happened in Korea. He sets off to find Raymond Shaw.

We soon learn is that Marco, Raymond and the rest of their platoon were shipped to Manchuria, China and brainwashed by Communists. The reason? They want to turn Raymond Shaw into the ultimate assassin. The communists have complete control over his mind and with a few simple words (”why don’t you pass the time by playing a little solitary”) and one visual cue (the queen of diamonds), Raymond is their puppet. Who he’s supposed to kill and how the communists came to choose Raymond I won’t reveal here because I want you all to rent this movie the next chance you have.

I first heard of The Manchurian Candidate in the late 80’s, when the film was being re-released after years of being out of circulation. At the time, there was speculation that Sinatra had had something to do with the film being held from public view, something to do with his close association with John F. Kennedy and the assassination plot in the film hitting to close to reality. To be honest, I didn’t care. I was just another film snob who thought Sinatra was a bad actor and that his films wouldn’t be worth seeing, no matter how much critics lavished praise on them.

Boy was I a fool.

In the mid 90’s, I happened to be sitting home on a weekday afternoon, flipping through the channels while waiting for inspiration to hit (we’ve all been there) and I turned on Turner Classic Movies just as The Manchurian Candidate had begun. Not realizing what I was watching I got sucked in by the tense first five minutes. I couldn’t stop watching. At this point in my life, my highfalutin ideal about what constitutes as art had mellowed considerably since my senior year of high school. Marriage will do that to you, as will surrounding yourself with a group of friends who work in special effects and their favorite movies of all time include the names Baker, Bottin and Harryhausen, not Ford, Kubrick or Scorsese. Thus, seeing Frank Sinatra’s name above the titles didn’t make me turn the channel. As the ads exclaim, the first five minutes of the film are vital to the understanding of the plot of The Manchurian Candidate. However, the film is so much more than just those five minutes.

Visually, Frankenheimer employed wonderful cinematography tricks to create a sense of paranoia and bewilderment. You need look no farther than Marco’s nightmare sequence. Frankenheimer wanted a single take in which the soldiers were seen sitting on stage at a New Jersey womens garden party and after the camera moves 360 degrees, they’re suddenly sitting in a Chinese amphitheater, being presented to a group of communists generals and their underlings. To achieve this effect, he had two sets build on railroad tracks. As the camera begins its circular pan around the room, showing ladies sitting in the audience, listening attentively about hydrangeas, the garden party stage set was pushed away by the film crew and the Chinese amphitheater stage was set in place. The actors jumped from one to the other and the 360 pan achieved a flawless transition between the brainwash garden party dream of the soldiers and the reality of being in the Chinese amphitheater. For any film enthusiast or budding filmmaker, the effect is mind-blowing.

Throughout the movie, Frankenheimer switched from hand held cameras, creating a documentary look, to locked-down cameras using extremely long lenses. Being shot in black and white gives the movie the feel of a classic, old movie, yet the modern techniques make it unique. The director also brought out the best in his actors. Sinatra is noble and heroic, but allows himself to look ugly and buffoonish when necessary. Angela Lansbury is downright evil as Raymond’s mother. Anyone whose only connection to the actress is her kind-hearted Murder She Wrote role will be shocked. The best performance comes from Harvey, who must make his unlikable character sympathetic. Raymond clearly knows that he’s unlovable, that he’s a stuck up jerk. Yet his heinous actions are not a result of just his upbringing. Raymond is a Cold War victim and in the end, he’s a tragic figure.

The lasting effect of The Manchurian Candidate in film history can be read about on critics’ lists and in books. For me, the lasting effect of this film is how much it inspires me each time I watch it. I want to pick up a camera and go experiment, to somehow create moving images like Frankenheimer did nearly 50 years ago. As a filmmaker, you can’t ask for much more in a movie, except to be entertained. The Manchurian Candidate does that to.

Comments