Mary Chapin Carpenter makes sadness sound good.

Mary Chapin Carpenter makes sadness sound good.

This is a gross oversimplification of her appeal, one which I hope to correct later on in this review, but at their best, Carpenter’s songs fill you with a bittersweet melancholy that somehow leaves you with a smile. She’s always excelled at storytelling songs, and finding the poetry in the day-to-day events of adult lives, but in the 15 years or so since her chart profile has dimmed, Carpenter’s writing has reached new levels of depth and shading, even as most people continue to remember her for earlier songs like “He Thinks He’ll Keep Her,” “The Hard Way,” and her cover of Lucinda Williams’ “Passionate Kisses.”

A perfect example of Carpenter’s post-spotlight brilliance is 2004’s Between Here and Gone, which eschewed radio hooks in favor of an album-length meditation on matters that either carried a deeply personal impact for her — such as the death of singer/songwriter Dave Carter — or subjects too topical for the airwaves, like the fear and unease in post-9/11 America. It sounds awfully trite, but those were raw, shaken times, and without ever resorting to preaching, Carpenter reached out and soothed her listeners’ jangled nerves. Who didn’t feel like the country had changed forever, and probably for the worse? Who wasn’t shaken at some level? Who didn’t wish they could just go back? Carpenter’s songs painted a picture of a time and a place when going back was no longer an option, but hope was nonetheless undimmed; no matter how harrowing the loneliness her music evoked, she still managed to suggest that comfort was never out of our grasp. In less skillful hands, a song like “Goodnight America” would have been angry, an anthem of spite and disillusionment; for Carpenter, it was a lullaby for crying times.

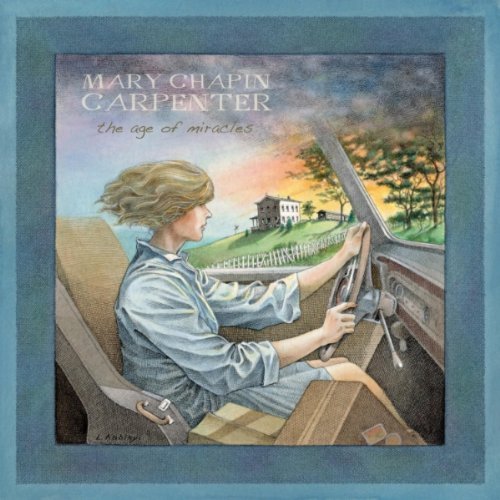

Her next album, 2007’s The Calling, was just as influenced by current events — Katrina was one of the themes — but musically, it felt less personal, and I worried that maybe Carpenter was trying to find her way back onto the country dial; Between Here and Gone marked the end of her long association with Columbia Nashville, and it seemed like The Calling was a bit of a self-conscious collection. I needn’t have worried: The Age of Miracles, begun while Carpenter recovered from a pulmonary embolism in 2007, contains some of her best, most poignant work.

Like any great songwriter, Carpenter manages to make the universal feel marvelously personal. Here, she uses the lives of some very public figures — including Ernest Hemingway’s first wife and Chinese activist Chen Guang — as inspiration, but she focuses on the threads that unite us; she doesn’t just tell their stories, or her stories, she tells our story. Katrina, Jena, Burma — she reclaims them from the 24-hour news cycle’s cutout bin and fits them back into the human experience.

All of which makes Mary Chapin Carpenter an uncommonly talented lyricist. But what makes The Age of Miracles such an absorbing listen is her gift for writing music to match the tales she tells. Her songs move with an easy motion; just as she sounds like she’s talking about all of us, her music feels like it’s taking us from place to place, gently rolling across the landscape. The piano rises and falls with the hills; the melodies are as plangent as the breeze; the guitar solos unspool as seductively as the horizon, glinting between the trees.

Am I overstating the case for what might be nothing more than a very well-crafted album? Possibly. Maybe The Age of Miracles won’t sound like this to you. All I know is that it gives me chills, and I think it’s full of that bittersweet melancholy that makes Carpenter’s work so great. It feels like traveling — heavy with the loneliness of not yet being where you want to be, and brimming with the hope that you’re almost there — and it moves you with a grace that makes the whole thing sound easy.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=b39b748a-293c-4744-945d-1378ef88e3ff)

Comments