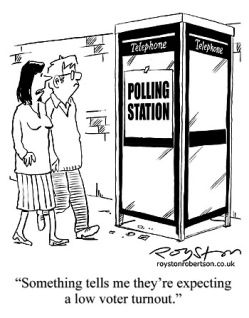

What if they gave a primary and nobody came?

To be more precise: What if they changed California’s primary system to encourage moderate candidates, level the financial playing field, and bring more voters to the polls … yet voters stayed home and well-heeled partisanship ruled anyway?

When I wrote last week about the chances for an upset in my congressional district’s first-ever open primary, I noted that independent candidate Linda Parks faced an uphill battle in her quest to freeze out the favored candidate of one of the major parties. She began the campaign with some distinct advantages: a popular county supervisor with nearly two decades’ experience in local government, she had high name recognition, a history of beating back well-financed challenges from major-party candidates, and four Democratic opponents to split the left-wing vote.

Yet she faced a couple of substantial obstacles as well. The first, of course, was the $1 million in negative and disingenuous advertising that has been shoveled atop her candidacy by the national Democratic Party. But the second was just as daunting. Californians clearly were just beginning to become acquainted with the open-primary system — a system they had created themselves with a 2010 ballot initiative. And in the run-up to Tuesday it was unclear whether voters who are not registered Democrats or Republicans — about a third of the electorate — would participate in a primary that until this year was reserved for the major parties. Parks needed those independents to turn up at the polls in June if she was to have a shot with them in November.

Yet she faced a couple of substantial obstacles as well. The first, of course, was the $1 million in negative and disingenuous advertising that has been shoveled atop her candidacy by the national Democratic Party. But the second was just as daunting. Californians clearly were just beginning to become acquainted with the open-primary system — a system they had created themselves with a 2010 ballot initiative. And in the run-up to Tuesday it was unclear whether voters who are not registered Democrats or Republicans — about a third of the electorate — would participate in a primary that until this year was reserved for the major parties. Parks needed those independents to turn up at the polls in June if she was to have a shot with them in November.

Well, they didn’t turn up — and hardly anybody else did, either. Turnout in the 26th congressional district primary was an anemic 25 percent, no higher than the traditional primary-day vote and certainly not enough to propel Parks into the general. She finished third with 18.5 percent of the vote, behind Republican Tony Strickland’s 44 percent and Democrat Julia Brownley’s 26 percent. (Jess Herrera, the Oxnard harbor commissioner who had so greatly impressed me during the campaign, finished a distant fourth with 6 percent — indicating, if nothing else, that Hispanic voters may require even more pre-primary outreach than others in the future, and certainly a lot more than Herrera could afford.)

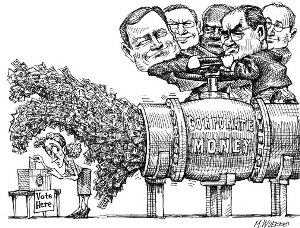

As the vote trickled in and the margin between Brownley and Parks proved wider than expected, it became clear that the new system is too young, voters are too unfamiliar with it, and it will be several election cycles before its full impact is felt in California politics. Indeed, its potential impact may never be felt, because it also became clear, as it has across the country this spring, that money — buckets and wheelbarrows and offshore bank accounts full of money — is fully capable, now more than ever, of clouding the public will and overwhelming every other possible factor in determining the outcome of American political races.

Mitt Romney began the winter loathed by sweeping majorities in his own party, yet he is now the Republican nominee after outspending his rivals (combined) by more than 7 to 1. Scott Walker’s campaign in Wisconsin outspent his rival’s by more than 10 to 1, and he turned back his recall by a seven-point margin. Here in California, an initiative to raise cigarette taxes began the spring polling at about 65 percent, yet after Big Tobacco outspent initiative proponents by 5 to 1 in April and May, the proposal lost by about 60,000 votes. And in Ventura County — where campaign officials just yesterday released internal polling from earlier in the spring that showed Parks up 10 points in late March and 6 points in early May — Brownley and the Democrats erased that advantage by outspending Parks 15 to 1, eventually paying $45 for every vote she received (compared to $4 for Parks).

Those last numbers don’t even account for the number of independent-minded voters who might have gone for Parks but wound up staying home, turned off by the deluge of vicious mailers portraying the moderate Parks as somewhere to the right of Sarah Palin and Dick Cheney. Such is the power of negative advertising — it’s intended not so much to bolster your own side as to disillusion and depress your opponent’s. And in a primary, when getting independents and lower-information voters to the polls is like pulling teeth anyway, the Democrats’ ability to throw the kitchen sink at their underfunded opponent no doubt delayed the arrival of the new era promised by California’s recent electoral changes.

Those last numbers don’t even account for the number of independent-minded voters who might have gone for Parks but wound up staying home, turned off by the deluge of vicious mailers portraying the moderate Parks as somewhere to the right of Sarah Palin and Dick Cheney. Such is the power of negative advertising — it’s intended not so much to bolster your own side as to disillusion and depress your opponent’s. And in a primary, when getting independents and lower-information voters to the polls is like pulling teeth anyway, the Democrats’ ability to throw the kitchen sink at their underfunded opponent no doubt delayed the arrival of the new era promised by California’s recent electoral changes.

”It took two million dollars and dishonesty to capture this race,” Parks wrote in a letter to supporters Wednesday, fudging the numbers considerably, ”and that is unfortunately an accurate reflection of our political system … We must not become disillusioned. The very fact that we are already disenfranchised by big money special interests demands we rise up. We must continue to see that the people are heard over the din of big money, or we will not only lose our moral compass by not rejecting what we know is wrong, we will also lose our representative government, and democracy is too precious for that.”

As the primary race fades and the bitterness of that portion of the campaign begins to fade — at least, Brownley had better hope it does — the district’s voters might receive a brief respite before the money machines power back up for the fall. Thanks to a series of developments in other congressional races around the state — including five races in which the top two finishers were both Democrats, and one in which two Republicans will compete in the fall — the Democratic party and affiliated super-PACs may decide to devote even more money to Brownley’s cause than they had been planning. Strickland already has amassed well over $1 million, and he was able to keep his powder dry throughout the spring; he is one of his party’s most prodigious fundraisers, and has already been designated a ”Young Gun” by the NRCC, so money will now flow to him from all manner of outside sources. He already has raised well over $50,000 just from current members of the GOP House majority.

When Strickland won his current seat in the state senate, in 2008, he did so by running the most expensive campaign in that body’s history against Democrat Hannah-Beth Jackson. He spent the lion’s share in a campaign that cost a total of $10 million, competing against a candidate from liberal Santa Barbara (dubbing her ”Taxin’ Jackson”) whom he could accuse of ”not sharing our (Ventura County) values.” With all his financial advantages, he won that race by a total of 900 votes out of more than 400,000 cast. Now he’s gearing up for another ludicrously expensive campaign against Brownley, who until February lived in liberal Santa Monica. So instead of Parks v. Strickland II, we’ll be witnessing a variation on Strickland v. Jackson II. You can bet the Republican will be ready, likely with the same financial advantages and largely the same argument.

When Strickland won his current seat in the state senate, in 2008, he did so by running the most expensive campaign in that body’s history against Democrat Hannah-Beth Jackson. He spent the lion’s share in a campaign that cost a total of $10 million, competing against a candidate from liberal Santa Barbara (dubbing her ”Taxin’ Jackson”) whom he could accuse of ”not sharing our (Ventura County) values.” With all his financial advantages, he won that race by a total of 900 votes out of more than 400,000 cast. Now he’s gearing up for another ludicrously expensive campaign against Brownley, who until February lived in liberal Santa Monica. So instead of Parks v. Strickland II, we’ll be witnessing a variation on Strickland v. Jackson II. You can bet the Republican will be ready, likely with the same financial advantages and largely the same argument.

Throughout the summer and fall I’ll continue this series by exploring the ways in which the two parties, and their candidates, can manage to spend upwards of $10 million in a suburban district with no television outlets of its own — a district where mass mailings of the sort that sunk Parks have always been the best way to reach voters. It should be a knock-down, drag-out brawl — potentially uglier, even, than the one-sided fight waged by Brownley this spring. It’s the kind of partisan warfare that, as a politics junkie of long standing, I’ve always hoped to witness at close range. But after watching Goliath take apart David this past month with attack after attack, as the Citizens United era of campaign financing thoroughly trumped California’s recent efforts at encouraging ”good government,” I’m not sure I’ll have the stomach to follow the money this fall without wishing a pox on all the parties involved. Stay tuned.

Comments