And we’re back! If you had half as much fun reading the first part of our Digging for Gold series as we did putting it together, well that means we enjoyed it twice as much. Where else can you go to get informed debate on topics ranging from World War I-era love songs to Snooki from Jersey Shore?

#6: Brenda Lee, “All Alone Am I” – #3 U.S., #7 U.K. Music by Greek musician Manos Hadjidakis, and was originally used in a film called The Island of the Brave.

#6: Brenda Lee, “All Alone Am I” – #3 U.S., #7 U.K. Music by Greek musician Manos Hadjidakis, and was originally used in a film called The Island of the Brave.

Jeff Giles – Dig those quavering vocals, boys and girls. In the days before we lost the Melisma Wars, this is how you let people know you were sad. Also: harpsichord!

Jack Feerick – Songs like this seem to exist only as a sort of employment program for harpsichord players and string arrangers. The details are all in place, but the song itself is pretty slight. The spoken-word repeat is there obviously as a callback to ”I’m Sorry,” but also to pad this thing out to an acceptable length for a single.

Jon Cummings – I have a major soft spot for Brenda Lee, whose early-’60s catalog ranks with the very best of them … even Roy Orbison and Phil Spector’s stuff. The sustained sob of this song is typical of what she was able to do at such a young age — other teen stars of the last 40 years can’t sniff her … well, insert your own euphemism here, because Brenda actually was a class act. You know how I decided to go back and check out all her old stuff? Because I wanted to know what Golden Earring was talking about when they sang, “Brenda Lee coming on strong.” It turns out “Coming On Strong” is an AWESOME song, and that got me hooked.

David Medsker – Weird to think that the Beatles are only a year or so away from this. This seems awfully quaint, even by ’50s standards, though I can’t shake the feeling that Quentin Tarantino will use this song in ironic fashion for an upcoming movie.

Dave Lifton – Goddamn, this song sucks.

#7: Gene Pitney, “Only Love Can Break a Heart” – #2 U.S., #4 Australia. A Hal David/Burt Bacharach joint.

#7: Gene Pitney, “Only Love Can Break a Heart” – #2 U.S., #4 Australia. A Hal David/Burt Bacharach joint.

Dw. Dunphy – I didn’t know Gene Pitney did “Only Love Can Break a Heart.” I recognize him from the vastly underrated “Backstage” and the overrated “Town Without Pity.” Sorry, but the delivery of the latter is just so melodramatic, I can’t take it after awhile.

Feerick – Bacharach and David are already throwing the pop rulebook out the window here. The structure is unconventional, to say the least — it’s all chorus, basically, with only brief tags of verse, and the middle eight dominates the thing. It’s damned odd, and there’s nothing much for me to latch onto.

Giles – Love can break a heart, but there isn’t a substance known to man that could have broken Gene’s glossy mane. Goddamn. Good for you, Gene.

This sounds like your average tremulous strings ‘n’ things pop ballad to me, but lest anyone doubt its effectiveness, just read the top comment at the video, which tells the heartbreaking tale of a retired GI who’s still pining for the girl who dumped him while he was fighting in Vietnam. I repeat: Goddamn.

Cummings – I find “Only Love Can Break a Heart” excruciating. Except for “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” I never got Pitney’s appeal — his voice bugs me. Something about “Liberty Valance” works, though — that whole story-song thing meshes with his overly enunciated vocals. That was his “lane,” as the Idol judges this year are so fond of saying. He needed to “stay in his lane.”

Dunphy – Funny you should say “lane” in this regard. I thought “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance” was sung by Frankie Laine.

Feerick – I dunno. I mean, Pitney was a huge and genuine talent, a songwriter and multi-instrumentalist who incorporated all kinds of innovative instrumentation into his work, but he sounds hamstrung here. The voice has elements of big-band croon with a community-theater quaver, but there’s a graininess on the low notes that makes me think this guy was holding back the raunch — he could have gotten low-down and dirty if he’d wanted. (He did hang out with the Rolling Stones, after all.) I do love the horn-and-whistling motif—it’s a characteristic Pitney arranging touch, and the old-timey whistling always reminds me of ”White Christmas” — but overall I reckon that Pitney was more comfortable singing his own songs, and that consequently ”Town Without Pity” is a much better record.

Medsker – Love the chorus to this. Those ghostly backing vocals are both pretty and a little terrifying.

Lifton – Goddamn, this song sucks.

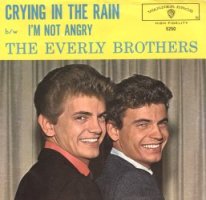

#8: The Everly Brothers, “Crying in the Rain” – #6 U.S. and U.K.; the second song on this disc co-written by Carole King.

#8: The Everly Brothers, “Crying in the Rain” – #6 U.S. and U.K.; the second song on this disc co-written by Carole King.

Dunphy – “Crying In The Rain” is one of my favorite Everly Bros. songs. I’m not sure why it sets itself apart in my mind from their other songs, but when I hear the name, I go to this song even before “Wake Up Little Susie.”

Giles – Once again, I will embarrass myself by stating publicly that a-ha’s cover of this song was the first version I heard.

Cummings – “Crying in the Rain” was practically the Everlys’ swan song as a chart-topping act. I love the drama of it — the way those boys could slow down a ballad to a snail’s pace and force you to focus on nothing but their harmonies was pure magic.

Medsker – Wow, this really stands out compared to the first two songs. It’s easy to lose sight of their influence without the proper context. These guys were clearly playing a different sport than everyone else.

Dunphy – I agree on the Everlys. They were aiming for a new pop sound while Brenda Lee and Gene Pitney both have feet still tentatively planted in Your Hit Parade.

Chris Holmes – I think if we were to put together a pie chart showing influences on the Beatles, there would be a fairly large slice for the Everly Brothers. And Chuck Berry.

Dunphy – Certainly on the level where vocal harmony is concerned, I agree.

Feerick – I can’t even write about the voices; what more is there to add? Only listen to the drums on this one — riding a light Latin groove, which of course was all the rage at the time; but dig the rolling toms, which simultaneously suggest the rumbling of distant thunder. A miraculous record, with all the elements working together.

Lifton – Goddamn, this song rules. I also love the cover by Dave Edmunds and Nick Lowe on the reissue of Rockpile’s Seconds Of Pleasure.

#9: Connie Francis, “Don’t Break the Heart That Loves You” – #1 U.S., the third and last for Francis.

#9: Connie Francis, “Don’t Break the Heart That Loves You” – #1 U.S., the third and last for Francis.

Giles – Now that’s a voice. And an amazing life, too — her Wikipedia page is like eight Lifetime movies in one.

Holmes – I already knew about the rape and her battle with depression/mental illness, which was awful enough. But when I read in her Wikipedia bio that her brother was killed by the Mafia I was like, “Oh come on now, this really is too much.”

Dunphy – “And then?”

“And then they tied Connie Francis to the railroad track!”

“And then? And then…?!”

Cummings – When I was 12 or 13 in the late ’70s, I thought Connie Francis had to be the most popular female singer in history, because her TV-marketed album was always being pitched during commercial breaks on Star Trek or whatever I was watching. All those hits! Those commercials just became ingrained in your subconscious — I can still reel off the names of at least a couple dozen Slim Whitman and Boxcar Willie songs, too. As far as I’m concerned, though, “Don’t Break the Heart that Loves You” was the least of Connie’s #1 singles. It certainly lacked the spark of so many of her earlier hits, and pointed the way toward her slide into dreary adult-contemporary drippiness.

Feerick – Duane Eddy-style twang + sweet double-tracked harmonies = a perfectly enjoyable way to spend two minutes. Too bad this song is three minutes long.

Okay, that’s a little unfair. ”Don’t Break the Heart” finishes strongly, but that spoken bridge is a massive buzzkill. I know it was en vogue at the time—see Brenda Lee, above—but you’ve got to pick your battles, guys. When you’ve got a song as banal and dopey as this one, you can skate along on charm (and I would argue that transcending banal material through charismatic performance is in fact that is the essence of pop in any era), but the last thing you want to do is force people to pay attention to the lyrics.

Medsker – I’m suddenly seeing in my head the young Catherine swooning to the music on her Walkman in Never Let Me Go.

Lifton – Great, now we’re back to sucking.

#10: The Duprees, “You Belong to Me” – #7 U.S.; this was covered by many others including Dean Martin in 1952. This was the only Top 10 song for the Duprees, and one of their four Top 40 singles.

#10: The Duprees, “You Belong to Me” – #7 U.S.; this was covered by many others including Dean Martin in 1952. This was the only Top 10 song for the Duprees, and one of their four Top 40 singles.

Dunphy – “You Belong to Me” has been done by almost everyone from that musical era, but this is my favorite go at it.

Giles – A fine song, but it’s a mystery to me why the audiences of the day felt the need to turn it into a hit three times in 10 years. And now I want to listen to the Doobies’ “You Belong to Me.”

Cummings – I own seven different versions of this song, from jazz (Benny Carter) to postwar-pop (Jo Stafford) to Marshall Crenshaw’s tribute to the Duprees — and while the Duprees’ own version is fine, it’s not my favorite. I always loved Patsy Cline’s rendition — I think the “Nashville Sound” offers a better context for the song than doo-wop does. But my favorite version is Carla Bruni’s boozy, emotive, English-as-a-second-language recording from a few years back. I’m kinda hot for Carla in general, actually, but that’s another story.

Medsker – Just seeing that name makes me think of Robbie Dupree, which makes me think of the time Jason Hare said, “Robbie Dupree? Fuck that guy.”

Sounds like a nice song to slow dance to at the sock hop.

Lifton – OK, I was about to write something about this being a nice arrangement of a pretty tune I’ve heard lots of times before, and then I listened to the lyrics. Basically, the guy’s saying, “Hey, have a nice trip around the world. You’d better not cheat on me.”

Feerick – Making it essentially the same scenario as the Beatles’ “All My Loving,” a year or two later, but with the roles reversed. It’s not a particularly odd sentiment. “Staying true” in the face of temptation (& especially travel) was a huge theme in postwar pop, for all kinds of obvious sociological reasons. More people were mobile; more young people were leaving home who might previously have never expected to do so, first to go to war and then to go to college (including my own father — God bless the G.I. Bill). The economic opportunity of the boom years had as its flipside all manner of cultural anxiety, and that comes out in the pop songs.

Dunphy – It’s not so different from last time’s “Sealed With a Kiss,” meaning, “You’re off to summer vacation, girl. I’m going to nag you by mail every day so you don’t have time to go to the beach for your midnight hookup.”

Feerick – “How Ya Gonna Keep ’em Down on the Farm (After They’ve Seen the Jersey Shore)?”

Dunphy – Well, if we’re talking about Snooki, you keep them down with a tranquilizer gun.

Tranquilizer optional.

Holmes – I’m not a music historian, but were songs about insecure lovers common prior to that era?

Cummings – That question’s an interesting one, Chris. I don’t begin to have universal knowledge of this stuff, but through my collecting of ancient pop songs I’ve noticed a few trends. The pop music of the minstrel era tended to be a lot jauntier in the face of hardship — lots of stiff-upper-lip Irish ballads and paeans to heroism, even during World War I. The “farewell for now” and nostalgic songs of the 19th century and early 20th (during the Boer War, for example, which was the biggest Anglo-Saxon conflict of the years immediately predating WWI) were more likely targeted to one’s parents — Stephen Foster songs like “Old Folks at Home” or “My Old Kentucky Home,” as well as Dan Quinn’s “My Mother Was a Lady,” an Irish ballad like “Ireland Must Be Heaven (For My Mother Came From There),” or Henry Burr’s WWI weeper “A Baby’s Prayer at Twilight (For Her Daddy Over There).” Others were chin-up, into-the-breach types (the Boer War fave “Goodbye, Dolly Gray”), or extrapolated separation into tragic death for the purpose of melodrama (any number of tearjerker ballads like “After the Ball” and “The Mansion of Aching Hearts” or Irving Berlin’s “When I Lost You.”).

At the end of WWI, however, a song called “Till We Meet Again” became a massive hit that directly (if really, really prosaically) addressed the wistfulness and insecurity of lovers’ separation. More came in the ’20s (Ben Selvin’s “Oh, How I Miss You Tonight,” Isham Jones’ “I’ll See You in My Dreams,” etc.), then Bing Crosby sang a number of them. WWII was when the genre exploded, as male crooners (Sinatra, Johnny Mercer, Dick Haymes) and girl singers (Doris Day, Dinah Shore, Jo Stafford) filled the radio with songs about being lovelorn for someone far away.

Jack says it quite well — the more mobile Americans became, thanks first to trains and cars and planes but later because of war and college and other permanent relocations, the more wistful and uncertain the balladry became. Of course, I’ve only been talking about the European-based “pop” music of the era — you could write a whole parallel bit on the acoustic blues and the way African-Americans (and whites too) channeled their separation woes (slavery & sharecropping, the northern migration, etc.) into gospel songs.

Tony Redman – Jon, don’t you mean “We’ll Meet Again” (“We’ll meet again. Don’t know where, don’t know when….”)?

Cummings – Nope. Different song. Here’s a link to the lyrics.

Redman – Oops, you’re right. Sorry about that. I got my wars mixed up! I always associated World War I with “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary,” but that could be Snoopy’s fault.

Related articles

- Digging for Gold: The Time-Life “AM Gold” Series, Part 2 (popdose.com)

- Digging for Gold: The Time-Life “AM Gold” Series, Part 1 (popdose.com)

Comments