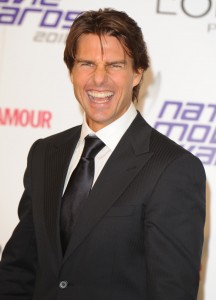

The big Tom Cruise summer movie Edge of Tomorrow came out last weekend. There’s a good chance that it went away as fast. In the onslaught of young adult novel adaptations, superhero antics, various examples of cgi-assisted badassery, there was little interest in the sci-fi film, even with fairly decent critical response. So it has been with most of Cruise’s movies. His last bona fide hit was Mission Impossible 4, but that has as much to do with the franchise support system as it does with star power. From there after, we’ve had Knight and Day, Rock of Ages, Jack Reacher, Oblivion and on. The name on the poster, always at the top, and nearly always bigger than the title itself, has become a millstone around the neck. I wouldn’t say Tom Cruise is box office poison yet, but he’s coming dangerously close.

The primary reason for this is because, of all the most famous actors we know, Cruise is one who takes the fewest risks. He is, in every movie, Tom Cruise first and character second. That’s fine if you still have a legion of fans invested in the celebrity more than the story, but Cruise has done damage to his career with his personal life, and if he insists on being “him” in everything he does, he has to expect the baggage to follow along. Unlike other celebs who go through divorces, Cruise detaches. There is no congeniality to be seen. You either are or you aren’t.

The primary reason for this is because, of all the most famous actors we know, Cruise is one who takes the fewest risks. He is, in every movie, Tom Cruise first and character second. That’s fine if you still have a legion of fans invested in the celebrity more than the story, but Cruise has done damage to his career with his personal life, and if he insists on being “him” in everything he does, he has to expect the baggage to follow along. Unlike other celebs who go through divorces, Cruise detaches. There is no congeniality to be seen. You either are or you aren’t.

We won’t throw in Cruise’s devotion to the Church of Scientology. I don’t feel it is fair to drag his faith into it. There are plenty of actors of faiths, and of no faiths, that produce good work. They blend seamlessly into the work, and it becomes bigger than they are, and that is a fundamental problem Cruise seems to have. Who, or what, his personal deity is has nothing to do with that, so we’re taking that off the table. What is left is still that conclusion that Cruise cannot ever be subservient to the work. He always seems to feel the need to stand on its neck with a crown and scepter, and to knock it in the head if it protests. That type of disharmony to the biostructure of an effective movie is commonly referred to “being thrown out of the picture.” It is a huge obstacle to view a Cruise film and not see him floating just outside of it.

So how can Mr. Mapother remedy this? The answer lies, most clearly, in Matthew McConaughey. Of all the people on God’s green earth who had reduced themselves to joke status, it was he with his surfer, stoner, Jack Johnson-loving bro-titude who had done massive damage to himself. He was always photographed on a beach with his shirt off. His vocal drawl ensured that no matter how hard he tried, the audience would see only McConaughey. His solution was to not let them see him. Use the drawl to his advantage. He lost weight, to an almost dangerous effect, to star in Dallas Buyers Club, the story of a man who has to face his own prejudices when given the death sentence of HIV AIDS. He played a southerner, and looked nothing like his former self. In a lot of the film he is not likeable. He is not a “bro.” He took down the outward barriers and then acted the hell out of the script, and was rewarded for it. When he edged back toward a more Matt-like look for his role in True Detective, he could now be accepted for the work, because he already had been.

Prior to Breaking Bad, Bryan Cranston was mainly known for comedic roles — Malcolm’s Dad on Malcolm In The Middle, Jerry Seinfeld’s dentist, and so on. With a shaved head, tighty whities, and a bad mustache, Cranston entered the world of Walter White, chemistry teacher dying of cancer; a tragic-comic figure. Over the next few years he would descend into one of the most potent and vicious anti-heroes television had ever witnessed. Nobody is relegating Cranston to strictly “comedic actor” department anymore.

Prior to Breaking Bad, Bryan Cranston was mainly known for comedic roles — Malcolm’s Dad on Malcolm In The Middle, Jerry Seinfeld’s dentist, and so on. With a shaved head, tighty whities, and a bad mustache, Cranston entered the world of Walter White, chemistry teacher dying of cancer; a tragic-comic figure. Over the next few years he would descend into one of the most potent and vicious anti-heroes television had ever witnessed. Nobody is relegating Cranston to strictly “comedic actor” department anymore.

Tom Cruise has a tough time trying to not be pretty. I wouldn’t suggest he starve himself, but if he wants to be taken as something other than Moviestar Tom Cruise, he’ll have to attempt to not look like him. That’s a given, but that’s also apparently incredibly tough for him to pull off. It isn’t because he cannot pull it off, but that he seems to refuse to pull it off. Cruise must always be the hero, even in those extremely rare moments he isn’t actually herioc. About the closest he ever got to the dark side were his performances in Magnolia, which tweaked his own “Isms” pretty hard; Collateral, where he played a gray-haired hitman; and Tropic Thunder, where he went the Full Eddie Murphy and transformed into a sleazy Hollywood scheisster. These are also roles that people gravitated to with much more affection than the grin-fest he tends to usually put on. To recollect one of his earlier successes, Cruise needs to aim more for Raymond Babbitt and less for Charlie Babbitt.

Cruise always needs to be the best, the show-off, the go-to, and if current movies and television are an indicator, that sort of character just won’t fly right now. Climbing buildings by hand in Dubai may work in the isolated world of the Mission Impossible movies, but audiences would have been just as impressed had he done it on a soundstage instead of him actually doing it. That didn’t really move the needle much for the film itself. It was more for Cruise’s need to always be the universe’s center, the ultimate. Ultimates have become boring. We don’t recognize them in our own world anymore. We cannot identify with them.

Cruise always needs to be the best, the show-off, the go-to, and if current movies and television are an indicator, that sort of character just won’t fly right now. Climbing buildings by hand in Dubai may work in the isolated world of the Mission Impossible movies, but audiences would have been just as impressed had he done it on a soundstage instead of him actually doing it. That didn’t really move the needle much for the film itself. It was more for Cruise’s need to always be the universe’s center, the ultimate. Ultimates have become boring. We don’t recognize them in our own world anymore. We cannot identify with them.

Another thing is, Cruise has devolved into three portrayals physically. They are: grinning, smug, uber-confidence; bug-eyed, trembling and in shock; and grimacing, teeth-gritted, as if he was passing a cactus out of his bowels. The past decade has been fraught with variations of these three, so it becomes infinitely easier to say Cruise is not right for a role, but that was never his problem. Cruise has so micro-managed his work, previously with production partner Paula Wagner, that he developed his own movies. It wasn’t a question of whether he was right for someone else’s roles. He stood there and, essentially, had the movie built around him, meaning there has seldom been a point where he was challenged. Few will tell the boss he’s wrong, and few will tell him to get scruffier. Every professional of any sort needs to have some kind of push-back to grow. That’s how you gain and nurture “range.”

Finally, Cruise thinks he’s funny, but he’s not. He needs to do a flat-out comedy. He needs to call up Paul Feig, Edgar Wright, or Judd Apatow and say, “I want to be an unemployed office worker with hair falling out, prospects looking dim, with annoying co-workers and a more annoying family, and a ‘love interest’ that hates my guts and is completely unattainable. And in the end, I do not attain her. I find love with a plain-Jane co-worker who doesn’t mind that I break out into hives when the temps rise past 74 degrees. I want to drive a ’74 AMC Pacer that I have to jump on to get the starter flywheel to engage. I want to wear Wal-mart off-the-rack clothes and Duck Dynasty t-shirts.”

Finally, Cruise thinks he’s funny, but he’s not. He needs to do a flat-out comedy. He needs to call up Paul Feig, Edgar Wright, or Judd Apatow and say, “I want to be an unemployed office worker with hair falling out, prospects looking dim, with annoying co-workers and a more annoying family, and a ‘love interest’ that hates my guts and is completely unattainable. And in the end, I do not attain her. I find love with a plain-Jane co-worker who doesn’t mind that I break out into hives when the temps rise past 74 degrees. I want to drive a ’74 AMC Pacer that I have to jump on to get the starter flywheel to engage. I want to wear Wal-mart off-the-rack clothes and Duck Dynasty t-shirts.”

If someone can chisel through the iron walls of presumed superiority Cruise has erected all around himself, people might care. He might become a box office draw once more. But is he capable of being someone who is incapable, perhaps a little incompetent, and perhaps a lot more human?

Comments