Editor’s Note: This post’s title, while summarizing the article accurately, is meant in the spirit of humor. What Hollywood truly needs now is for the AMPTP to negotiate with the Writers Guild and SAG-AFTRA in good faith and get actors and screenwriters back to work with fair deals.

But once writers and actors come back, all involved need to take a hard look at the glorified abuse of excess it has slovenly bundled itself within for the past few years. Rampant expenses, ridiculously long run times, a culture that uses CGI not as a storytelling tool or a band-aid, but as the entire goal with the story itself being the band-aid. All these contribute to an industry making product that cannot be profitable without divine intervention (or a memeable portmanteau).

Not gonna lie – the summer of 2023, despite the wild successes of Greta Gerwig’s Barbie and Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, will go down as a mess. even before the strikes. Heading into the summer movie season, Marvel attempted to redeem itself from all the bad press it got from the failure of Antman & the Wasp: Quantumania. It did so with Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3, but curiously, fans took the shine away from Marvel and put it squarely on director James Gunn’s shoulders. It is like a collective punishment from them. “No, no, Marvel. He gets all the cake now. None for you.”

Superheroes did not fare as badly as some would believe, with Spider-Man Across the Spider-Verse doing more than respectable business. The alleged fatigue seemingly forgot about Miles Morales and Peter Quill…but over on the Warner Bros. lot, the expensive and controversy-laden The Flash received more than punishment from the fans. It got a full skull-kick that not even the return of Michael Keaton as Batman could shield away. Some will say it was terrible CG effects. (Could be, rabbit, could be.) Others will claim that the lead-heavy use of nostalgia weighed it down. (You might, rabbit, you might.) But truly, the damning of The Flash was the lighted match of actor Ezra Miller and their many, very serious crimes committed during and after filming, left unaddressed and unresolved in a cowardly gamble foisted by the studio, believing short-term memory, assorted TikTokery, and Gen Z IDGAF would render all this as meaningless come opening day.

Superheroes did not fare as badly as some would believe, with Spider-Man Across the Spider-Verse doing more than respectable business. The alleged fatigue seemingly forgot about Miles Morales and Peter Quill…but over on the Warner Bros. lot, the expensive and controversy-laden The Flash received more than punishment from the fans. It got a full skull-kick that not even the return of Michael Keaton as Batman could shield away. Some will say it was terrible CG effects. (Could be, rabbit, could be.) Others will claim that the lead-heavy use of nostalgia weighed it down. (You might, rabbit, you might.) But truly, the damning of The Flash was the lighted match of actor Ezra Miller and their many, very serious crimes committed during and after filming, left unaddressed and unresolved in a cowardly gamble foisted by the studio, believing short-term memory, assorted TikTokery, and Gen Z IDGAF would render all this as meaningless come opening day.

It turns out that not only was the audience still in full possession of its memory, but probably did not want to reward Miller by association of their actions. Lighted match…kaboom.

And Indiana Jones? And Ethan Hunt? Folks, it’s a lot.

Most pundits agree that production costs have spiraled upward and out of control. A 200-mil dollar production needs to triple that to get anywhere near profitability, mainly because marketing these films is so bloody expensive. (After all, it takes a lot of scratch to license a famous pop tune, remix it with “epic” orchestral backing, and slap it on your trailers while you pretend you did something totally new.)

But what can be done?

Three Little Letters

Cast your mind back to the year 1982. It was a golden age for home video entertainment. Starting in the late-1970s and throughout the Eighties, the freedom of capturing a television broadcast to rewatch it at any time of your choosing could be intoxicating. Many built up collections of recordings not of things they’d really want to revisit, but more because they could. It was like stealing fire from the gods, if fire were episodes of The Smurfs in syndication.

Key to the topic at hand, the VHS (video home system) videotape was crowned the king of the format wars over Sony’s Beta version. VHS had three settings for recording: SLP (standard long play) which gave the user six hours of recording time but overall terrible video and audio quality; the intermediate LP of four hours, which had better performance but was not compatible with some VHS players; and SP, or Standard Play, which was just as advertised, the industry standard. SP was two hours, sometimes two-and-a-half with thinner but more fragile tape formulations to fit the cassette’s spools.

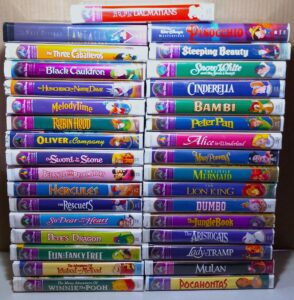

At the same time of VHS’ rise to dominance Hollywood was experiencing a golden age in the movie theater. Just Google the list of movies that came out in 1982. Some are box office champions, some are all-time classics, and even those which performed poorly in theaters eventually became cult favorites. Some of that resurrecting power came from being rerun endlessly on cable television, but more than that, VHS tape rental stores drove the secondary market to new profitability. This, in turn, created a desire for film ownership, and studios were only too happy to deliver tapes at “sell-through” pricing so that families could, as Disney once chirped, “bring the magic home.”

At the same time of VHS’ rise to dominance Hollywood was experiencing a golden age in the movie theater. Just Google the list of movies that came out in 1982. Some are box office champions, some are all-time classics, and even those which performed poorly in theaters eventually became cult favorites. Some of that resurrecting power came from being rerun endlessly on cable television, but more than that, VHS tape rental stores drove the secondary market to new profitability. This, in turn, created a desire for film ownership, and studios were only too happy to deliver tapes at “sell-through” pricing so that families could, as Disney once chirped, “bring the magic home.”

There were no guarantees that VHS tapes would save your film from being derided, unprofitable, and left to the potential graveyard of lost media. Therefore, it was crucial to keep budgets under control. Add to that the amount of movies coming out had to bow to sheer physics. The burgeoning Multiplex phenomenon still had to contend with five or six screens, not twelve. The films were delivered AS FILM on multiple reels that would degrade over successive screenings. Striking prints, sending them out to theaters, having equipment that might be 10-or-more years old, all these meant that the viewing experience might not be…ideal. You likely were making films with a thought to how many screenings you could fit in per day, but also where they would go after the theatrical run.

So here’s the deal. Keep your movies under two hours so that VHS tapes could handle them. Make the special effects eye-popping and dazzling, but keep their occurrences brief so that you aren’t emptying your budget out every ten minutes of the run time. Make your soundtracks great and exciting for the theaters, but remember that only a few homes had stereo televisions, much less stereo VHS decks. At each turn, home video imposed limitations that kept the movies more affordable to produce on the whole, but also erected hurdles filmmakers innovated their ways around. Productions weren’t hindered as much as they were challenged, and those who could work around these to tell satisfying stories did so, to fame, acclaim, profitability, and more.

24-Hour Pizza and Chekhov’s Gun

Cut back to 2023. Home viewing is vastly different with streaming dominating the process. Flat-screen TVs of widening sizes and shockingly good audio quality literally bring the movie experience home. Streaming TV shows can offer a story that can be from one hour up to 12 hours, depending on how long you make your show’s season, and are remarkably cinematic in nature. You can see and hear everything, but should you?

Playwright Anton Chekhov was purportedly quoted as saying, “If you introduce a gun in the first act, you must fire it by the third act.” Any element you introduce into your narrative should be crucial to that narrative. Worldbuilding is nice in a book that only costs the author’s time, but is a gushing wound to the wallet on the screen if it has no bearing on the story.

Think about some of the tightest, most satisfying movies from the 1980s. No thread at the beginning of Back to the Future remains untied, thanks to the “flash card” methodology of screenwriters Bob Gale and Robert Zemeckis. Card one introduces and idea and card two resolves it. If there is no card two, you don’t need card one. If you need card one to make sense of the overall story, you better damn well create a card two that justifies it.

Think about some of the tightest, most satisfying movies from the 1980s. No thread at the beginning of Back to the Future remains untied, thanks to the “flash card” methodology of screenwriters Bob Gale and Robert Zemeckis. Card one introduces and idea and card two resolves it. If there is no card two, you don’t need card one. If you need card one to make sense of the overall story, you better damn well create a card two that justifies it.

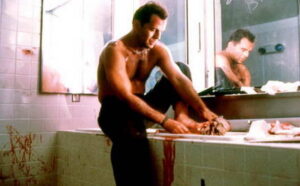

This same plot rigor is found in the action classic Die Hard. Any odd interaction at the start of the film gets a callback later, from a random stranger telling John McClane (Bruce Willis) to relieve his stress by making fists of his bare feet, to later trying it out after a spiky exchange with his estranged wife Holly (Bonnie Bedelia). This sets up an even later scene where a battered and bruised McClane has to pick shards of broken glass out of his bleeding feet.

What these scenes do not have are exhaustive special effects scenes of Marty McFly’s skateboard, either his off-the-shelf one in 1985 or his kit-bashed one in the 1950s. We don’t have deep fly-bys of every wrinkle and toe-hair of Bruce Willis’ tootsies. And even on today’s steroid-pumped home theaters, we still don’t need them. And we did not need them in the VHS era, either. Story – conflict and resolution on every scale – was paramount.

What these scenes do not have are exhaustive special effects scenes of Marty McFly’s skateboard, either his off-the-shelf one in 1985 or his kit-bashed one in the 1950s. We don’t have deep fly-bys of every wrinkle and toe-hair of Bruce Willis’ tootsies. And even on today’s steroid-pumped home theaters, we still don’t need them. And we did not need them in the VHS era, either. Story – conflict and resolution on every scale – was paramount.

Today? Well, you don’t have to stay under that 2-hour mark anymore. VHS and DVD for that matter are considered dinosaur fossils. You’re shooting for IMAX, baby. You need to see every digitally captured pore, and make them up in a digital workstation if you can’t. Those people in the back channel of the Dolby Atmos soundtrack debating what to make for dinner tonight, even though they and their digestive systems have nothing to do with the story? Louder, and more of them! Put ’em on the ceiling if you have to. Your story calls for only one space-bound dogfight. How about three more? One slice of pizza is good? Eat the whole pie. Two pies. Eat until you are sick.

And if that makes the movie 3+ hours long, who cares? At least it will keep your competitors out of your auditoriums.

Some Fixes, Free of Charge

From critics to casual viewers, the death of the tight, precisely paced movie is being mourned nationwide with complaints on lips and numbness in buttocks. Over the past 5 years, “That movie is too damn long,” has become far too common. That time costs money. Cut your budget by cutting out all those First Act guns that go nowhere.

Likewise, you can reduce your mixing budget by removing audio that’s there just because you can put it there.Is that surround conversation really necessary?

Likewise, you can reduce your mixing budget by removing audio that’s there just because you can put it there.Is that surround conversation really necessary?

Be more careful on-set when shooting and recording dialogue and you can spend less time/money rerecording in ADR (automated dialogue replacement). And try framing your scene more carefully so the viewer won’t see boom microphones overhead. You won’t have to CG-erase them later. Look deep into your script and be harsh. What’s there for the story and what’s there just for showing off? Do you need extensive color grading throughout, or merely want it?

I know I am beating this horse corpse into paste, but I have to believe that Hollywood needs to get back to basics by imposing restrictions upon itself, making productions less costly. That doesn’t mean making them worse, but instead positioning them to get to profitability faster. You don’t HAVE to pretend you’re gunning for VHS presentation at a specific time, resolution, audio quality, whatever to get there. However, the modern age of excess is mostly just flexing. It moves from telling the best story you can to killing your budget because you can.

And sometimes you do need to erase the odd water bottle or Starbucks coffee cup from your scene. Sometimes you have to remove unprompted plane/train/Steve noises from your soundtrack. These used to be odd exceptions from happenstance, not the standard due to a lack of discipline.

We’re never going back to VHS tapes, but maybe Hollywood can help itself by thinking like they are.

Comments