Music fans will argue non-stop about a lot of things, but most of us understand that there’s a generally agreed-upon order when it comes to the way certain things are experienced — like, for instance, our discovery of classic songs. Ask a dozen people to rank the best of Otis Redding, Tom Petty, or the Beatles, and you’re probably going to get about a dozen very different answers — and a single broad consensus regarding some of the greatest music of the rock era.

Music fans will argue non-stop about a lot of things, but most of us understand that there’s a generally agreed-upon order when it comes to the way certain things are experienced — like, for instance, our discovery of classic songs. Ask a dozen people to rank the best of Otis Redding, Tom Petty, or the Beatles, and you’re probably going to get about a dozen very different answers — and a single broad consensus regarding some of the greatest music of the rock era.

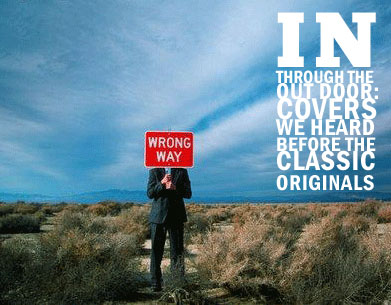

Of course, just because things are supposed to happen a certain way, that doesn’t mean they always do — and we’ve got the collection of ass-backwards musical discoveries to prove it. From Stevie Wonder to Al Green, Eddie Floyd, and Joni Mitchell, here’s a list of classic songs we heard the wrong way: through covers by other artists.

Surely you have a few “in through the out door” moments in your own musical history. Share them in the comments!

Like Billy Joel (whom I have to mention in everything I write for Popdose to piss off Ted Asregadoo), the Black Crowes worked best as a gateway band, one you dug until you discovered the better work of their influences. I was working in a record store at this point, and I remember playing a younger co-worker “Sister Luck” and the Rolling Stones’ “Sway” back-to-back to prove to him how indebted they were to the Stones. My love for that first album also made me realize that Rod Stewart wasn’t a complete jagoff, and I began to track down Faces albums, which were surprisingly hard to find where I was living. Suddenly, Ronnie Lane’s songs on Rough Mix, the album he did with Pete Townshend, began to make sense. But it was their blistering cover of Otis Redding’s “Hard to Handle” that had the biggest impact on me. I wanted to hear the original, so I bought a Best Of cassette and it blew my mind. It freed soul music from the narrow constraints of oldies radio, and I began to explore the depths of the catalogs of the great soul labels of the 50s and 60s. —Dave Lifton

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/mtLbE3IUY2U" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

I didn’t know what the hell a Tom Petty was in 1981. After all, I was either four or five at the time, and at the time, my only exposure to Petty in my non-AOR radio listening household would have been a snippet of “Don’t Do Me Like That” or “Refugee” on Soul Train or America’s Top Ten. So, pardon me for thinking that Grace Jones’ version of “Breakdown” (featured on the Warm Leatherette album as well as being the B-side of her Top 5 R&B hit “Pull Up to the Bumper” was the original — nay, the only — version of the song in existence. I thought this way for over a decade, not hearing Petty’s original until after purchasing his greatest hits compilation in the mid-’90s.

I don’t think “loose” is a word that many people use in reference to Petty’s music, but Jones’ version can practically be used as an ironing board, with an icy cold groove courtesy of producers Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare. Grace’s vocal delivery is as seductively authoritarian as ever — while Petty sounds stoned on his version, Jones sounds like she’s going to sex you up then kill you. While the rational part of me likes both versions equally, there’s a small part of my brain that still considers Jones’ rendition to be definitive. Maybe after hearing the song, I’m just afraid that Grace will come after me and break me in half. –Mike Heyliger

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/U53TqEm9GzU" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

My introduction to some of Stevie Wonder‘s most beautiful songs have been through George Michael, who has covered at least ten either on record or in concert. The first one I heard was both: the B-side to the 12″ of “Father Figure” was “Love’s In Need of Love Today,” recorded live at a concert in April of 1987. The second was a cover of “They Won’t Go When I Go,” included on Listen Without Prejudice, Vol. 1. Not every singer has the voice (or the balls) to cover an artist like Wonder, but in both cases Michael did admirably, retaining the songs’ original keys and imbuing both with passion. “Love’s In Need of Love Today” benefited from his always-spot-on touring musicians, while “They Won’t Go When I Go” was wisely pared down, featuring only a pianist and a sea of Michael-provided backing vocals. Both became favorites of mine, years before I actually heard the originals.

![102c228348a052bf8a96e010.L._SCLZZZZZZZ_[1]](https://popdose.com/wp-content/uploads/102c228348a052bf8a96e010.L._SCLZZZZZZZ_1.jpg) For many, the cover version becomes the definitive version if they’ve heard it first, regardless of whether it’s actually a better treatment of the song. I was surprised when, in both cases, the original surpassed the cover. “Love’s In Need of Love Today,” the opening track from Songs in the Key of Life, has its greatest impact during the final half of the song: repeated on-the-fly ad-libs from Wonder, preaching his message of love. While the song is over seven minutes long, it never feels belabored or repetitive, and given their personal nature, I’m thankful Michael opted to leave the ad-libs out of his version. And while Michael does a fantastic job on “They Won’t Go When I Go,” giving the song its necessary desperate, pleading quality, he simply can’t reach Wonder’s scope of emotional range. Giving Wonder the edge is his brilliant use of the T.O.N.T.O synthesizer, featured prominently throughout the track while never actually distracting from Wonder’s lead and backing vocals. Though always a strong singer with an impressive range, it’s only in recent years that Michael has been able to find the nuance within his vocal quality to match the lyrics he’s singing, and it’s absent from both of these covers.

For many, the cover version becomes the definitive version if they’ve heard it first, regardless of whether it’s actually a better treatment of the song. I was surprised when, in both cases, the original surpassed the cover. “Love’s In Need of Love Today,” the opening track from Songs in the Key of Life, has its greatest impact during the final half of the song: repeated on-the-fly ad-libs from Wonder, preaching his message of love. While the song is over seven minutes long, it never feels belabored or repetitive, and given their personal nature, I’m thankful Michael opted to leave the ad-libs out of his version. And while Michael does a fantastic job on “They Won’t Go When I Go,” giving the song its necessary desperate, pleading quality, he simply can’t reach Wonder’s scope of emotional range. Giving Wonder the edge is his brilliant use of the T.O.N.T.O synthesizer, featured prominently throughout the track while never actually distracting from Wonder’s lead and backing vocals. Though always a strong singer with an impressive range, it’s only in recent years that Michael has been able to find the nuance within his vocal quality to match the lyrics he’s singing, and it’s absent from both of these covers.

Still, I continue to listen to both versions of each song, and while George Michael continues to be a fine interpreter of Wonder’s catalogue (“Blame It On the Sun,” “Too Shy To Say,” “Living For the City,” “Knocks Me Off My Feet,” “Another Star” and “As,” to name but a few), there’s no comparison. Not that it’s a fair fight, anyway; nobody can top Stevie Wonder. —Jason Hare

I don’t think “loose” is a word that many people use in reference to Petty’s music, but Jones’ version can practically be used as an ironing board, with an icy cold groove courtesy of producers Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare. Grace’s vocal delivery is as seductively authoritarian as ever-while Petty sounds stoned on his version, Jones sounds like she’s going to sex you up then kill you. While the rational part of me likes both versions equally, there’s a small part of my brain that still considers Jones’ rendition to be definitive. Maybe after hearing the song, I’m just afraid that Grace will come after me and break me in half.

The funny thing — and by ”funny” here I mean, of course, ”pathetic and embarrassing” — is that I like Joni Mitchell. Like any other boy growing up in a house full of sisters, I must have heard Court and Spark about ten thousand times in the 1970s, and For the Roses not much less. As I grew older, Hejira became one of my desert island discs; I found Turbulent Indigo seriously underrated, and even harbor a soft spot for Chalk Mark in a Rainstorm.

But picking up on an artist when they’re already well into a career is sort of like walking into a movie that’s half-over. You can pick up the general shape of what’s going on, sort out the themes and approaches, but there are going to be some blank spots and lacunae in your comprehension. My understanding of Joni Mitchell the songwriter was as a keen observationalist, a sketch artist, crafting short stories with conflicted and believable characters in a few well-chosen details.

And based on my exposure to her work, to the albums toward which I gravitated, that’s a fair assessment. But it is an incomplete one: It misses an entire phase of her career, when she essentially founded the confessional school of singer-songwriterdom, mining her personal relationships for song-fodder, analyzing and dissecting her own emotional life without fear, and sparing herself nothing.

![51Fl1OPa7RL._SCLZZZZZZZ_[1]](https://popdose.com/wp-content/uploads/51Fl1OPa7RL._SCLZZZZZZZ_1.jpg) It misses, in a word, Blue. Just as I missed Blue. Which is why, when I first heard Aimee Mann’s version of ”River” (download) some Decembers ago, presented without attribution on some mp3blog or other, I assumed it was a brand-new song.

It misses, in a word, Blue. Just as I missed Blue. Which is why, when I first heard Aimee Mann’s version of ”River” (download) some Decembers ago, presented without attribution on some mp3blog or other, I assumed it was a brand-new song.

Which makes this a story about Aimee Mann, too, and how I could have taken ”River” for one of hers. Mann is, I reckon, a difficult genius on a Mitchell level. Since her days fronting til tuesday, she’s been working in dark, emotionally-complex territories. Like Mitchell, she’s an unsparing and fearless writer, and like Mitchell she has remained firmly in control of her own presentation and profession.

Mann, though, has always had a snarky edge to her that’s largely absent in Mitchell — which is why the introspection of ”River” is so arresting, coming from her. We always knew she had a cutting way with a put-down, but to hear a line like, ”I’m so hard to handle, I’m selfish and I’m sad / Now I’ve gone and lost the best baby that I ever had,” is to hear all her weary bitterness turned inwards, just for a moment; the slipping of the cynical mask, and a glimpse at the vulnerability beneath.

In its original context, ”River” has a very different impact; part of that difference in the effect of the two versions can be chalked up to the thirtysome years of gender politics that divide Joni Mitchell in 1971 from Aimee Mann today. Heard now, Blue sounds like the work of a woman in dire need of a little feminist consciousness-raising. The album finds Mitchell locked in the masochistic exercise of trying to balance a creative identity with a deep desire to conform to a more traditional ideal of femininity. It’s a rich theme, and one to which Mitchell would return throughout her career; but on Blue, there’s a streak of self-annihilation to the proceedings; she makes excuses for her lover’s bad behavior, blames herself for possessing the very honesty and drive that makes her fascinating, puts herself down for failing to be a doormat. (The way she calls her lover her ”Daddy” and her ”Old Man” just makes it creepier.)

”River” is, at least in part, about the way that devotion to a career can destroy a personal relationship. While Mitchell is no less careerist than Mann, the difference is that Mann generally feels no need to apologize for it. When Mann sings, ”I’m gonna make a lot of money, then I’m gonna quit this crazy scene,” there’s the tiniest hint of a smirk in her voice; you know and she knows that she’s going to do no such thing. Mann doesn’t need a relationship to complete her in the way that Mitchell does — not to the degree where she will abnegate her creative self for the sake of her boyfriend’s precious ego. Oh, in a moment of loss and grief, she will turn the possibility over in her mind — three decades of feminism have brought us only so far — but you know damned well how that argument is going to end.

”River” has become an unlikely sort of holiday staple — in the last five years, it’s been subject to nearly as many cover versions as ”Hallelujah” — but Mann’s take remains my favorite. Part of it that is the arrangement — the subtle orchestration, the hazy shimmer of the prepared piano. And Mann’s little voice, neither as powerful nor as flexible an instrument as Mitchell’s, beautifully conveys the song’s pathos. More than that, the effect of Mann’s ”River” comes from its context within her body of work, just as the resonance of Mitchell’s comes from its placement on Blue. Mann conjures a very specific emotional place — a fleeting moment of discontent and longing — while Mitchell’s take is a symptom of an entire pathology.

But the funny thing — and by ”funny,” here I mean ”ironic and maybe a little profound” — is that Mitchell herself, in the arc of her career, came around more or less to Mann’s position. By the time she made Hejira, Mitchell was still examining the balance between her work and her love life, but she’s largely made her peace; she’s getting home in the wee small hours with her reel-to-reel, but she’s able to look her coyote right in the face and say, ”No regrets.” None? Well, maybe a few. But that’s just part of the human condition. Just ask Robert Downey, Jr. He knows.—Jack Feerick

I’m pretty sure the first time I heard “Take Me to the River” was when I was 11 or 12, watching Saturday Night Live reruns on a little black-and-white TV in my bedroom in East Brunswick, some time in 1981 or ’82. I’m sure I reacted to the performance with disdain or something like it. David Byrne’s elastic and hiccupy delivery likely had little effect on me, so wrapped up was I in the long-haired, big-willied, loud-guitared crunch and boom of the period’s arena rock.

Over time, though, I grew to quite enjoy the song. The Franz/Weymouth rhythm section is the key to everything—it builds the funky foundation over which Byrne could do his mad-scientist-as-soul-man vocal and smack out a sketchy rhythm guitar figure, one that danced playfully with Jerry Harrison’s fanciful keyboards. Even with Brian Eno’s pasty British fingers twiddling knobs in the production booth, “Take Me to the River” felt soulful and alive in the hands of the Heads—a rare cross-pollination of New York New Wave and deep Memphis R&B.

Of course, much later—probably while spending every moment I could in a DJ booth or radio production room my first two years of college—I stumbled upon a little thing called Al Green Explores Your Mind, and discovered what “Take Me to the River” sounded like without the CBGB pedigree of Byrne and company. The unfiltered Memphis soul sound—drummer Howard Grimes’ tuhtuh-tap-tuhtuh-tap, the understated organ of Charles Hodges, the authoritative R&B expressions of the Memphis Horns —was at once exhilarating and confusing. The exhilarating part was the performance, and the sound of Green’s voice in full command; Explores Your Mind captures him at the absolute height of his powers, and those powers will lay you out if you’re not careful.

Hearing Green’s “River” was a little confusing, however, because I was used to recognizing it as a Talking Heads song. You can’t deny how special the song is—Foghat, Annie Lennox, the Grateful Dead, and a few dozen others have weighed in with their own takes. To this day, though, I think I prefer the first version I heard—the slinky Heads cover—to the more authentically soulful original. Ironically, my head says Al Green, while my soul remains attached to the Talking Heads. –Rob Smith

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/ngrXi5Dwk2I" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

I first heard “You Don’t Own Me” while listening to my mom’s copy of the Dirty Dancing soundtrack when I was nine years old. I hadn’t yet watched the film — Mom wouldn’t let me and it would be several months before my friends and I would sneak and watch it at a slumber party. I had no idea who the Blow Monkeys were and I didn’t know that their version of the song wasn’t the original (though, I did think it was strange that a boy would be singing lyrics like, “don’t say I can’t go with other boys”). I knew that the movie was set in the early 1960s, so I thought that all the music, save the Bill Medley/Jennifer Warnes hit “(I’ve Had) The Time of My Life,” came from the same era. But I was a little suspicious that might not be the case because several of the songs did not sound very ’60s, but I just didn’t know.

When I was in junior high, I finally heard the Lesley Gore original, on, appropriately enough, a jukebox my friend’s parents had in their basement. When it started playing, my first thought was, “Hey! This woman is singing that song from Dirty Dancing!” And I actually said that out loud. And I got laughed at by my friend’s mother. She then explained that this was, in fact, the original version of that song and that the singer was a teenager when she recorded it. I felt pretty silly and when it finished, asked that the song be played again. It made more sense to me being sung by Gore and the next time I heard the Blow Monkeys version, I was annoyed, both at myself for not knowing that it wasn’t the original and that it wasn’t as good as the original. I appreciate the cover more now, and I’m able to laugh at myself for my ignorance about the song’s origins. –Kelly Stitzel

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/FeOw0PGehbU" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

For an 8-year-old boy in 1974, Grand Funk’s “The Loco-Motion” was a perfect gateway drug into the world of pop music: crunchy guitar chords, a simple (and train-oriented!) lyric sung appealingly off-key, layers of echo that made a transistor radio sound like it had been flushed down the toilet, and those sublimely meatheaded backing vocals. Somehow the track fit perfectly amidst the other cheese that dominated pop radio that spring and summer, from “Seasons in the Sun” to “Dark Lady” to “Billy Don’t Be a Hero” and on and on. It was quite a year — and Grand Funk became, for a short time, my favorite band (Grand Funk Hits was my first album purchase). It wasn’t until years later that I learned “The Loco-Motion” was a cover … a cover of a song originally recorded by a 16-year-old girl, no less. Eventually I heard Little Eva, and recognized the amazing malleability of pop. If a song like “The Loco-Motion” could start as a staple of the Brill Building sound, then be transformed into a slab of irresistible cheese-metal, what couldn’t a pop song do? Of course, a few years later the U.K. production triumverate Stock-Aitken-Waterman brought the song back to its girl-pop roots, providing Kylie Minogue with a Top 5 hit in the U.S. in 1988 — and making “The Loco-Motion” the only song in the rock era to reach the Top 5 sung by three different artists in three different decades. And somewhere out there must be a few million Gen-Xers for whom Kylie’s boppy, brain-free rendition helped create an insatiable jones for pop music, just as those meatheads in Grand Funk did for me. –Jon Cummings

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/lNNW0SPkChI" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

It was spring of 1979. I was 10 years old, living in Ft. Lauderdale with my dad and brother. Dad’s running an errand near the airport. It’s a pretty remote area. Dad even said he’d let me drive the car around in this open area near the hangar. Sweet. (Of course, no one said ‘sweet’ back then. I probably said ‘Far out’ or something else embarrassing.)

Until he gets back, brother Steve and I are listening to the radio. The Miami Top 40 station is on (Y100, I believe), and they are playing a song that is blowing my fragile little mind. It was in this strange time signature that I would later learn was 6/4. It had this chugging keyboard part (or is it a guitar?) and thunder and lightning sounds in it. Sound effects in a pop song! Why don’t all songs have sound effects? And volcanoes. Definitely could use volcanoes.

As the parents of two very white Ohioans, no one was around to tell me that this was a cover of a 1966 Eddie Floyd song. In fact, it would decades before I heard the original, or even another cover (Jeff Healey played it in Road House, if memory serves). So as far as I knew, that wacky disco song – which has one discotastic promo video – was Amii Stewart’s song, or at least something someone wrote for her. Then I heard the original, and immediately understood how Stewart’s version cannibalized it, but at the same time, I understood why her version was such a huge hit. In a genre ruled by sameness, there wasn’t another disco song out there that sounded quite like “Knock on Wood.” Different drum sounds, a non-4/4 time signature, and sound effects: it was as right-place-right-time as disco songs got. Which was unfortunate for Stewart, because it would prove to be her only hit.

My dad got back to the car shortly after it was over, and the endorphins were clearly in control. Dad let me sit behind the wheel and get a feel for the gas pedal, but I’m so amped up about the song that I rev the car’s engine upwards of 40 miles per hour. Dad realizes that shifting the car out of Park is not such a good idea, and I take my place in the back seat, counting the seconds until I hear the ‘thunder and lightning’ song again. –David Medsker

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/1ztZ7WFo3nw" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

The Georgia Satellites hit chart paydirt with one of the few AOR novelty songs of the ’80s, but they weren’t a novelty band — just a group of good ol’ boys who liked to have fun playing rock ‘n’ roll. And they proved it with their impeccable choice in cover tunes, many of which functioned as gateways into the world of real classic rock for my impressionable teenage mind: they tackled Rod Stewart’s “Every Picture Tells a Story” on their debut record, exhumed “Hippy Hippy Shake” for the Cocktail soundtrack, and piled a mountain of joyously overdriven slide guitar on Joe South’s “Games People Play” on their third release.

Their second album, 1988’s Open All Night, is a bit of a mixed bag, as evidenced by the pair of covers stuffed into the track listing. No one needed another version of “Whole Lotta Shakin’,” and the Satellites surely knew it — but they made up for that lazy choice with their rockabilly-tinged take on “Don’t Pass Me By.” In its original incarnation — which I heard years later — it’s a lurching, country-spiced oddity on the Beatles’ White Album, a limp, right-angled thing that served as Ringo Starr’s first solo songwriting credit (and answered any questions as to why he hadn’t stepped out on his own earlier).

The Satellites took “Don’t Pass Me By,” turned it up loud, and blasted it wide open. Featuring a terrific cameo from peerless pianist Ian McLagan, thrashing drums, and 4:53 of tuneful hollering, it’s an album highlight — something acknowledged by the band in the liner notes, where they thanked Starr for “the right royal rave-up.” Even today, listening to the original makes me impatient. –Jeff Giles

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/xSd4evT8Nw8" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

Comments